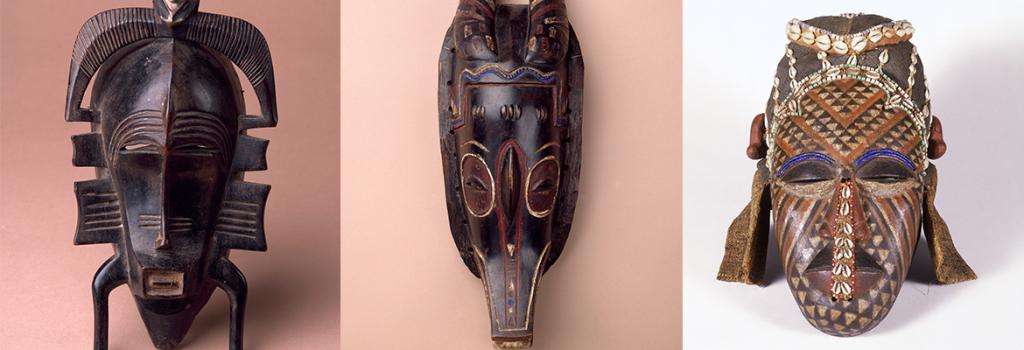

African Sculpture

In the early 1960s the museum was rebuilt after having been bombed in 1941. Following its long post-war limbo, the institution was assigned a government War Damage Fund in 1963 in order to help rebuild the collections. A large part of the fund was assigned to the Ethnology Department, under its new Keeper of Ethnography Richard Hutchings.

This is part of the Africa collection.

On taking up his post, Hutchings decided to concentrate resources on acquiring works of ‘primitive art’, as he called it. He had the idea that he would plug ‘gaps’ in the museum’s holdings of art from Africa and Oceania. Museum records show that Hutchings spent much of his War Damage Fund on masks and figures from French-speaking West and Central Africa, bought mainly from art galleries in London, Paris, and the Netherlands. He also bought a few pieces at auctions in London.

Before buying African pieces, Hutchings consulted William Fagg, a ‘keeper’ of ethnography at the British Museum with a special interest in African sculpture. Fagg introduced Hutchings to the French art dealer Charles Ratton in 1967, and Hutchings bought four African works from Ratton in Paris that year. Ratton had hosted innovative Surrealist exhibitions during the 1930s. He also collaborated with the Musée d’Ethnographie in Paris to put on an exhibition brass and ivory artefacts looted from the city of Benin in 1897 by a British military force.

Ratton wrote books and essays on African sculpture and, like some other dealers, he developed close links with museum curators and artists, as well as collectors of African sculpture. Together they helped to promote certain types of African sculpted works as ‘art’, rather than ethnographic specimens. They especially valued old, well-used, finely finished masks and figures, which they considered authentic as long as they showed no signs of twentieth-century modernization or European influence.

Many of the West African pieces that Hutchings bought for the museum in the 1960s conformed to a cannon of ‘famous art styles’ that appealed to European tastes of the time in showing a stylised realism, often combined with refined carving, and beautifully aged or polished surfaces.

You can read more about some of these works in chapter eight of Zachary Kingdon’s book on World Museum Liverpool’s African collection titled, Ethnographic Collecting and African Agency in Early Colonial West Africa, London and New York: Bloomsbury (published 27 December 2018).