The allure of Mary Wollstonecraft

What is it about the Walker Art Gallery's portrait of 18th-century feminist visionary Mary Wollstonecraft that makes it so intriguing? We take a look at the portrait, compare it to others of Wollstonecraft, and try and figure out the mystery behind its creator.

There are few images of Mary Wollstonecraft that are known today. Although her 1792 publication, Vindication of the Rights of Women, survives as a key feminist text, her actual image has largely been lost. However, one image captured during Wollstonecraft’s lifetime gives a particularly striking insight into her nature.

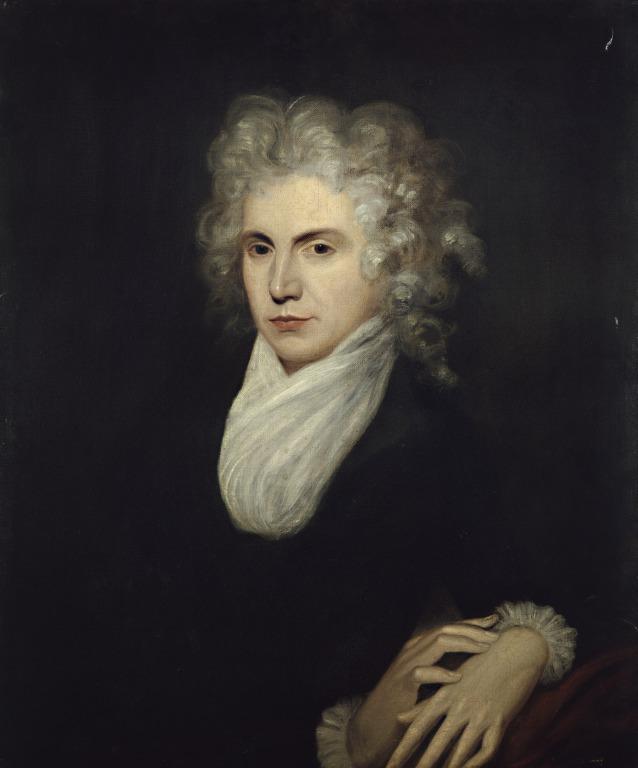

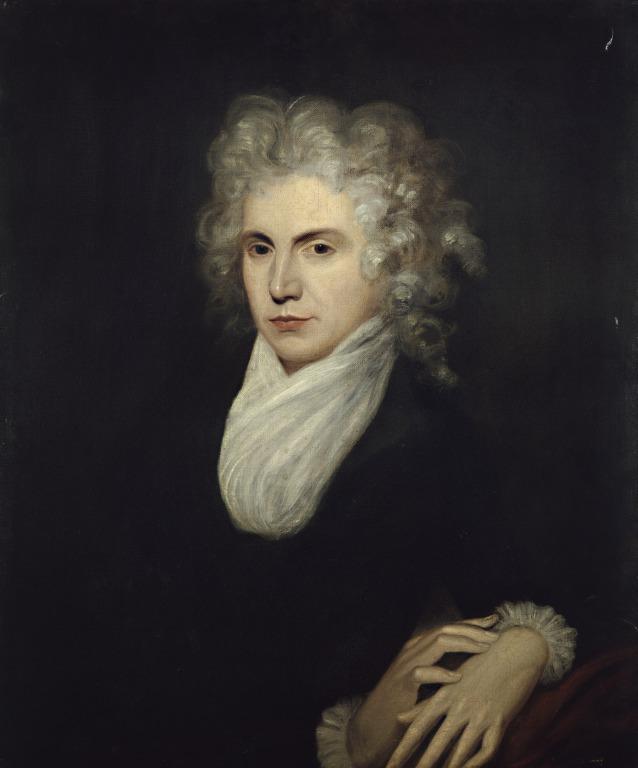

Our portrait of Wollstonecraft is a unique and captivating image. In the portrait, attributed to John Williamson, Wollstonecraft emerges as a powerful, asexual and atypical 18th-century woman. In a powdered wig, clad in the revolutionary style of French intellectuals, Wollstonecraft stares right back at us. It also provokes questions, who was the painter John Williamson, and was he actually the painter? Why did William Roscoe, the Liverpool revolutionary, commission the painting? What did Mary think of it? And most importantly why is it not this powerful image that comes to mind when we think of Wollstonecraft, but rather the soft, beautified, pregnant John Opie version?

Mary Wollstonecraft, John Williamson Attributed to; British School Previously attributed to, 1791

As part of our project Pride and Prejudice in 2016 we interviewed scholars and experts about images of Wollstonecraft but few of them were aware that the Walker’s portrait existed. However, when we organised a series of events celebrating Wollstonecraft, we saw firsthand how well people responded to Williamson’s portrait. The comment that was usually made was that she looked ‘strong’, ‘smart’ and ‘proud’. The Opie portrait certainly shows us Wollstonecraft, but it does not show us those traits. In fact, the Walker’s portrait is doing what Opie’s portrait never could do – it is inspiring artists to again consider Wollstonecraft.

As part of our research we sought to understand why this painting had not yet received the critical attention it deserves. We wondered whether or not the public reach of the painting had been affected by the attribution of the portrait to Williamson, an artist not as well known as Opie. Archive material from the Walker Gallery shows that the attribution has, in any case, been a consistent source of debate. Letters questioning the attribution have been arriving at the Walker for decades, and as late as the 1990s, with some even suggesting the portrait may be by Opie after all.

Mary Wollstonecraft by John Opie oil on canvas, circa 1797, NPG 1237

© National Portrait Gallery, London

After our investigation we do not feel able to confidently say that the portrait was done by Williamson. We do, however, have no better suggestion except to question if it actually matters. Whether it is Williamson or not, the painter of this extraordinary painting certainly deserves some praise.

This is not second-rate portraiture, this is great art. The portrait is now available to view online as part of National Museums Liverpool’s Pride and Prejudice project, which aimed to bring objects within the collections that are relevant to LGBTQ+ culture and identity to the fore.

You can also learn more about Mary Wollstonecraft in our video series Walker Women.

Research by Lucy Johnson and Camilla Mørk Røstvik