Could World Museum have some of the oldest human remains in Europe?

Dr Emma Pomeroy from Liverpool John Moores University reveals all about some exciting discoveries in World Museum's collections.

We're excited to announce a new collaborative project led by researchers from the School of Natural Sciences and Psychology at Liverpool John Moores University and World Museum. The project will radiocarbon date five human teeth and part of a jawbone from World Museum's collections. These all come from the same site that yielded the oldest known human remains from north-west Europe. These teeth and jaw could be important evidence for some of the earliest members of our species in

George Smerdon, site foreman for William Pengelly’s excavations, at the entrance to Kent’s Cavern in 1890. Photo from the British Geological Surve

the UK.

Kent's Cavern, near Torquay in Devon, has been known as an important paleontological and archaeological site since it was first excavated in the 19th century. Various people have excavated the caves, most notably William Pengelly who worked there from 1858-1880, and excavations continue today. As well as bones from Ice Age animals like rhinoceros, bears, hyenas and lions, and stone tools produced by early humans, various fragments of human bones and teeth were also found in this network of caves. Some of these human bones are relatively recent, dating to the Medieval period or later, while others such as the KC-4 maxilla (upper jaw bone) date as far back as 43-42,000 years ago.

Some of these finds found their way to World Museum in the 1940s, following the death of Willoughby Ellis. He had volunteered at the Torquay Museum where much of the Kent's Material is still kept, and obtained a significant quantity of the finds from the excavations at Kent's. During his life and after his death, these bones and artefacts found their way into museum and University collections around the UK and beyond.

George Smerdon, site foreman for William Pengelly’s excavations, at the entrance to Kent’s Cavern in 1890. Photo from the British Geological Surve

the UK.

Kent's Cavern, near Torquay in Devon, has been known as an important paleontological and archaeological site since it was first excavated in the 19th century. Various people have excavated the caves, most notably William Pengelly who worked there from 1858-1880, and excavations continue today. As well as bones from Ice Age animals like rhinoceros, bears, hyenas and lions, and stone tools produced by early humans, various fragments of human bones and teeth were also found in this network of caves. Some of these human bones are relatively recent, dating to the Medieval period or later, while others such as the KC-4 maxilla (upper jaw bone) date as far back as 43-42,000 years ago.

Some of these finds found their way to World Museum in the 1940s, following the death of Willoughby Ellis. He had volunteered at the Torquay Museum where much of the Kent's Material is still kept, and obtained a significant quantity of the finds from the excavations at Kent's. During his life and after his death, these bones and artefacts found their way into museum and University collections around the UK and beyond.

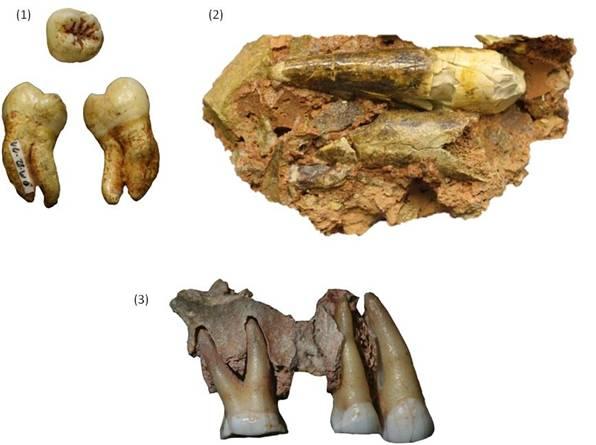

The upper jaw bone and five loose teeth from Kent's Cavern in the World Museum collections

After visiting the World Museum collections in April, Dr Isabelle De Groote and I, both human bone specialists from Liverpool John Moores University, realised that the Kent's human remains at World Museum had not been described in scientific publications before. Recognising these could be important evidence of the earliest humans in this part of the world, we won a grant from the Natural Environment Research Council to radiocarbon date the specimens at the University of Oxford's Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit (ORAU). Professor Higham and his team dated the KC-4 maxilla from Kent's Cavern, which is still the oldest evidence of our species in the UK.

While we're very excited, we're bracing ourselves for a real roller-coaster ride!

Radiocarbon dating will only work if the organic part of the teeth and bone are well enough preserved. While methods for radiocarbon dating continue to improve, it's not been possible to date some remains from Kent's in the past. The famous KC-4 maxilla from the site, the oldest human remains in north-west Europe, could not be dated directly, only by dating animal bones found above and below it.

But even if we can date the teeth, we already know that some human remains from Kent's are very recent, so it’s possible that these are just a few hundred year old. Much of the material excavated by Pengelly was assigned a number so that its precise location in the cave can be identified to within less than a metre. This approach was really pioneering for archaeological excavations at Pengelly's time. If we knew where in the cave the teeth and jaw came from, that would give us an idea of roughly how old they might be. Unfortunately, this information on the human remains from the World Museum collections must have been lost long ago.

Nonetheless, we do have a few clues. The oldest material from Kent's Cavern (before 10,000 years ago) was found in a distinct red-coloured deposit (soil), and one of the WML teeth has traces of a similar coloured soil still stuck to it.

The upper jaw bone and five loose teeth from Kent's Cavern in the World Museum collections

After visiting the World Museum collections in April, Dr Isabelle De Groote and I, both human bone specialists from Liverpool John Moores University, realised that the Kent's human remains at World Museum had not been described in scientific publications before. Recognising these could be important evidence of the earliest humans in this part of the world, we won a grant from the Natural Environment Research Council to radiocarbon date the specimens at the University of Oxford's Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit (ORAU). Professor Higham and his team dated the KC-4 maxilla from Kent's Cavern, which is still the oldest evidence of our species in the UK.

While we're very excited, we're bracing ourselves for a real roller-coaster ride!

Radiocarbon dating will only work if the organic part of the teeth and bone are well enough preserved. While methods for radiocarbon dating continue to improve, it's not been possible to date some remains from Kent's in the past. The famous KC-4 maxilla from the site, the oldest human remains in north-west Europe, could not be dated directly, only by dating animal bones found above and below it.

But even if we can date the teeth, we already know that some human remains from Kent's are very recent, so it’s possible that these are just a few hundred year old. Much of the material excavated by Pengelly was assigned a number so that its precise location in the cave can be identified to within less than a metre. This approach was really pioneering for archaeological excavations at Pengelly's time. If we knew where in the cave the teeth and jaw came from, that would give us an idea of roughly how old they might be. Unfortunately, this information on the human remains from the World Museum collections must have been lost long ago.

Nonetheless, we do have a few clues. The oldest material from Kent's Cavern (before 10,000 years ago) was found in a distinct red-coloured deposit (soil), and one of the WML teeth has traces of a similar coloured soil still stuck to it.

One of the teeth from Kent's Cavern, a lower wisdom tooth (number LIVCM 44.28.WE.3), in the collections of World Museum (1). This has red soil sticking to it, similar to the soils found in the older layers of the cave. An example is shown in image 2, which is a carnivore tooth still embedded in the 'red breccia' from the cave. Similar red colouring can also be seen on the KC-4 maxilla in Torquay Museum which was dated to around 42-43,000 years old.

The other specimens have traces of a much more brown coloured soil on them, suggesting they might be younger. Several of the teeth have large cavities, which tend to be more common in people who lived within the last few thousand years than in people who lived much longer ago. The only way to be really sure how old the remains are though is to radiocarbon date them.

Even if the teeth and jaw prove to be more recent, that is important information too. Once we know how old they are, they can be used for research about people and their health at that particular time.

One of the teeth from Kent's Cavern, a lower wisdom tooth (number LIVCM 44.28.WE.3), in the collections of World Museum (1). This has red soil sticking to it, similar to the soils found in the older layers of the cave. An example is shown in image 2, which is a carnivore tooth still embedded in the 'red breccia' from the cave. Similar red colouring can also be seen on the KC-4 maxilla in Torquay Museum which was dated to around 42-43,000 years old.

The other specimens have traces of a much more brown coloured soil on them, suggesting they might be younger. Several of the teeth have large cavities, which tend to be more common in people who lived within the last few thousand years than in people who lived much longer ago. The only way to be really sure how old the remains are though is to radiocarbon date them.

Even if the teeth and jaw prove to be more recent, that is important information too. Once we know how old they are, they can be used for research about people and their health at that particular time.

George Smerdon, site foreman for William Pengelly’s excavations, at the entrance to Kent’s Cavern in 1890. Photo from the British Geological Surve

the UK.

Kent's Cavern, near Torquay in Devon, has been known as an important paleontological and archaeological site since it was first excavated in the 19th century. Various people have excavated the caves, most notably William Pengelly who worked there from 1858-1880, and excavations continue today. As well as bones from Ice Age animals like rhinoceros, bears, hyenas and lions, and stone tools produced by early humans, various fragments of human bones and teeth were also found in this network of caves. Some of these human bones are relatively recent, dating to the Medieval period or later, while others such as the KC-4 maxilla (upper jaw bone) date as far back as 43-42,000 years ago.

Some of these finds found their way to World Museum in the 1940s, following the death of Willoughby Ellis. He had volunteered at the Torquay Museum where much of the Kent's Material is still kept, and obtained a significant quantity of the finds from the excavations at Kent's. During his life and after his death, these bones and artefacts found their way into museum and University collections around the UK and beyond.

George Smerdon, site foreman for William Pengelly’s excavations, at the entrance to Kent’s Cavern in 1890. Photo from the British Geological Surve

the UK.

Kent's Cavern, near Torquay in Devon, has been known as an important paleontological and archaeological site since it was first excavated in the 19th century. Various people have excavated the caves, most notably William Pengelly who worked there from 1858-1880, and excavations continue today. As well as bones from Ice Age animals like rhinoceros, bears, hyenas and lions, and stone tools produced by early humans, various fragments of human bones and teeth were also found in this network of caves. Some of these human bones are relatively recent, dating to the Medieval period or later, while others such as the KC-4 maxilla (upper jaw bone) date as far back as 43-42,000 years ago.

Some of these finds found their way to World Museum in the 1940s, following the death of Willoughby Ellis. He had volunteered at the Torquay Museum where much of the Kent's Material is still kept, and obtained a significant quantity of the finds from the excavations at Kent's. During his life and after his death, these bones and artefacts found their way into museum and University collections around the UK and beyond.

The upper jaw bone and five loose teeth from Kent's Cavern in the World Museum collections

After visiting the World Museum collections in April, Dr Isabelle De Groote and I, both human bone specialists from Liverpool John Moores University, realised that the Kent's human remains at World Museum had not been described in scientific publications before. Recognising these could be important evidence of the earliest humans in this part of the world, we won a grant from the Natural Environment Research Council to radiocarbon date the specimens at the University of Oxford's Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit (ORAU). Professor Higham and his team dated the KC-4 maxilla from Kent's Cavern, which is still the oldest evidence of our species in the UK.

While we're very excited, we're bracing ourselves for a real roller-coaster ride!

Radiocarbon dating will only work if the organic part of the teeth and bone are well enough preserved. While methods for radiocarbon dating continue to improve, it's not been possible to date some remains from Kent's in the past. The famous KC-4 maxilla from the site, the oldest human remains in north-west Europe, could not be dated directly, only by dating animal bones found above and below it.

But even if we can date the teeth, we already know that some human remains from Kent's are very recent, so it’s possible that these are just a few hundred year old. Much of the material excavated by Pengelly was assigned a number so that its precise location in the cave can be identified to within less than a metre. This approach was really pioneering for archaeological excavations at Pengelly's time. If we knew where in the cave the teeth and jaw came from, that would give us an idea of roughly how old they might be. Unfortunately, this information on the human remains from the World Museum collections must have been lost long ago.

Nonetheless, we do have a few clues. The oldest material from Kent's Cavern (before 10,000 years ago) was found in a distinct red-coloured deposit (soil), and one of the WML teeth has traces of a similar coloured soil still stuck to it.

The upper jaw bone and five loose teeth from Kent's Cavern in the World Museum collections

After visiting the World Museum collections in April, Dr Isabelle De Groote and I, both human bone specialists from Liverpool John Moores University, realised that the Kent's human remains at World Museum had not been described in scientific publications before. Recognising these could be important evidence of the earliest humans in this part of the world, we won a grant from the Natural Environment Research Council to radiocarbon date the specimens at the University of Oxford's Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit (ORAU). Professor Higham and his team dated the KC-4 maxilla from Kent's Cavern, which is still the oldest evidence of our species in the UK.

While we're very excited, we're bracing ourselves for a real roller-coaster ride!

Radiocarbon dating will only work if the organic part of the teeth and bone are well enough preserved. While methods for radiocarbon dating continue to improve, it's not been possible to date some remains from Kent's in the past. The famous KC-4 maxilla from the site, the oldest human remains in north-west Europe, could not be dated directly, only by dating animal bones found above and below it.

But even if we can date the teeth, we already know that some human remains from Kent's are very recent, so it’s possible that these are just a few hundred year old. Much of the material excavated by Pengelly was assigned a number so that its precise location in the cave can be identified to within less than a metre. This approach was really pioneering for archaeological excavations at Pengelly's time. If we knew where in the cave the teeth and jaw came from, that would give us an idea of roughly how old they might be. Unfortunately, this information on the human remains from the World Museum collections must have been lost long ago.

Nonetheless, we do have a few clues. The oldest material from Kent's Cavern (before 10,000 years ago) was found in a distinct red-coloured deposit (soil), and one of the WML teeth has traces of a similar coloured soil still stuck to it.

One of the teeth from Kent's Cavern, a lower wisdom tooth (number LIVCM 44.28.WE.3), in the collections of World Museum (1). This has red soil sticking to it, similar to the soils found in the older layers of the cave. An example is shown in image 2, which is a carnivore tooth still embedded in the 'red breccia' from the cave. Similar red colouring can also be seen on the KC-4 maxilla in Torquay Museum which was dated to around 42-43,000 years old.

The other specimens have traces of a much more brown coloured soil on them, suggesting they might be younger. Several of the teeth have large cavities, which tend to be more common in people who lived within the last few thousand years than in people who lived much longer ago. The only way to be really sure how old the remains are though is to radiocarbon date them.

Even if the teeth and jaw prove to be more recent, that is important information too. Once we know how old they are, they can be used for research about people and their health at that particular time.

One of the teeth from Kent's Cavern, a lower wisdom tooth (number LIVCM 44.28.WE.3), in the collections of World Museum (1). This has red soil sticking to it, similar to the soils found in the older layers of the cave. An example is shown in image 2, which is a carnivore tooth still embedded in the 'red breccia' from the cave. Similar red colouring can also be seen on the KC-4 maxilla in Torquay Museum which was dated to around 42-43,000 years old.

The other specimens have traces of a much more brown coloured soil on them, suggesting they might be younger. Several of the teeth have large cavities, which tend to be more common in people who lived within the last few thousand years than in people who lived much longer ago. The only way to be really sure how old the remains are though is to radiocarbon date them.

Even if the teeth and jaw prove to be more recent, that is important information too. Once we know how old they are, they can be used for research about people and their health at that particular time.