The cultural legacy and history of the Maya civilisation

In this guest blog, Dr Niamh Thornton, Senior Lecturer in Latin American Studies at the Department of Modern Languages and Cultures at the University of Liverpool gives us an insight into the cultural legacy and history of the Maya civilisation. She also shares with us some resources, for those who have been inspired by the 'Mayas: revelation of an endless time' exhibition to learn more.

An introduction

The Maya civilisation can be traced back to 7000 BCE . They had a hieroglyphic form of writing, were experienced astronomers, and had important mathematical breakthroughs that preceded those of other early cultures. For example, in 357AD they discovered and used zero, a concept that is integral to the development of complex mathematical systems. In recent years the Mayas became world news when some misinterpretations of the Maya calendar spread. These fears incorrectly predicted the end of the world. In brief, Maya time started in 3,114 BCE and is broken into cycles of 394 years called Baktuns. The 13th Baktun finished on the 21st of December 2012, which led some to conclude that this meant that time and, therefore, the world was coming to an end. Thankfully, they were wrong. Instead, it was the date when an old calendar cycle was over making way for a new beginning. We are now in the early stages of the new 394 year calendar cycle rather than the feared for apocalypse.

The present

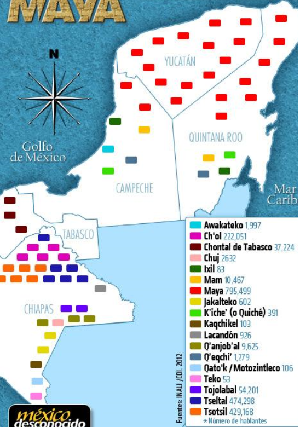

As well as the ancient Mayas who created the objects on display in 'Mayas: revelation of an endless time', it is important to remember the present day Mayas. There is considerable linguistic and creative diversity among the modern Mayas with 69 distinct languages, according to UNESCO. Currently they live in Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador, and Honduras. This map shows the variety of languages in Mexico alone.

Foto: Las lenguas mayas en México./ Apolo Castrejón

Of the twenty languages some, such as Teko, is spoken by as few as 53 people, while there are over 424,000 speakers of Tseltal. Mexico is a country proud of its diverse cultural heritage, what in Spanish is called mestizaje. This has involved a commitment to the important contribution that the indigenous peoples have made to Mexican identity and culture, not least in the food, such as corn flour tortillas, chilli, guacamole, and chocolate that are commonplace in many of our diets today, but also in the preservation of the cultural heritage that can be seen in the 'Mayas: revelation of an endless time' exhibition.

Despite this commitment and respect for the past, the Mayas still experience prejudice, discrimination and poverty despite attempts to remedy this. Films and books Throughout modern history the Mayas have asserted their rights to their ways of managing land, practising their religions, speaking their languages, and preserving their traditions, and have demanded these from the Mexican authorities, through different means. At present, there are groups who have set up autonomous communities in Chiapas in Southern Mexico as an attempt at finding new ways of self-government. A great way to find out more about these communities is by watching a recent film, Corazón del tiempo/Heart of Time (Alberto Cortés, 2009) written by Hermann Bellinghausen, a journalist who has long worked in Southern Mexico.

The film is a love story about a young woman who is torn between her responsibilities and her hopes and aspirations for the future and was made in close collaboration with the Maya communities who act in the film. It gives a sense of what life is like for some Maya people today.

Listen out for the music by two Cuban musicians, Descemer Bueno and Kelvis Ochoa, who worked alongside a local band, La Marimba de San José del Río, and women and children from Chiapas, as well as the Mexican rock star Cecilia Toussaint, who sings a ranchera (a type of Mexican music involving folk ballads using guitars and horns), and a Catalan group, Ojos de brujo.

It is a good introduction to political activism and to the way of life of contemporary Mayas. There is a wealth of novels about the Maya for those who are keen to learn more.

The poet and novelist, Rosario Castellanos, wrote two. The first, Balún-Canán (1957), translated by Irene Nicholson as The Nine Guardians, tells the story of the dramatic changes and tensions caused by government reforms in Mexico in the early part of the Twentieth century from a young child’s point of view. The child has more sympathy for the indigenous people who are to benefit from the reforms than for her wealthy landowning parents. Castellanos’ other novel set in Chiapas, Southern Mexico, is Oficio de tinieblas (1962), translated by Esther Allen as The Book of Lamentations. It is a darker novel about struggles for land and freedom. Castellanos was not indigenous and there are a growing number of indigenous poets and authors publishing, especially since the 1980s.

Two texts from indigenous sources are the Chilam Balam and the Popol Vuh. The first is an account of colonial times from the perspective of a learned Mayan priest and scholar and the second is a collection of mytho-historical stories. Both are important insights into distinct cultures and world visions. For children, there are a number of books that tell Mayan stories. Two examples of these are The Story of Colours: A Bilingual Folktale from the Jungles of Chiapas (1999), which is beautifully illustrated by Domitila Domínguez, as too is Linda Lowery’s The Chocolate Tree: A Mayan Folktale (2009).

This is just a brief summary and is to be considered as merely a starting point. The Mayas are an important grouping who have a long and rich history, and knowing more about their past will help understand Mexico’s present. The Mayas exhibition at World Museum until 18 October 2015 is a unique opportunity to see a sample of the wealth of creativity by an ancient culture whose legacy lives on.