Did photography kill the woodblock print star?

Toyohara Kunichika’s prints capture an exciting time of change in 19th century Japan and give a fascinating insight into the impact of early photography on traditional print making. Frank Milner takes a look at this clash of cultures.

Photography, first invented around 1837, came late to Japan. The earliest surviving daguerrotype photograph of a Japanese person dates from about 1845 and the first Japanese-run photographic studio only opened in the mid 1860s.

Small portrait photographs had for many years been affordable to thousands of Europeans and Americans but were still a novel, modern, highly fashionable and quite expensive thing to own in 1870s Tokyo.

This 1870 woodblock print I think captures well the sense of novelty and excitement surrounding photographic images in Japan at this time .

It shows a young woman called Kogiku (Little Chrysanthemum), a geisha and beauty. In the top corner there is an image of a sake bottle and dish of food advertising a famous Tokyo restaurant.

Kogichu's dress fabric is a fashionable design - this is a portrait of a woman who is perfectly on trend.

She stares intently at two ‘carte de visite’ photographs. One of these appears to be a portrait, although it is not clear that it is a picture of herself. The other photograph held in her right hand shows the address and trademark of the Tokyo photographic studio run by Uchida Kiuchi, the man who became the official photographer to the Emperor of Japan.

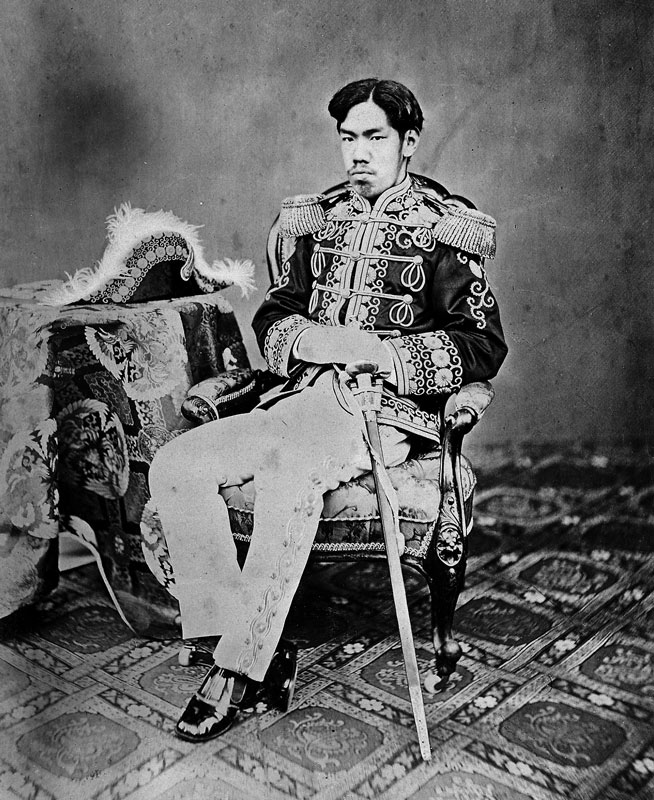

Whereas in the past it had been forbidden for ordinary Japanese people to even look at the face of the Emperor, from 1873 onwards the Imperial photographic image was widely distributed and displayed in schools and government buildings. The cutting-edge medium of photography was deliberately used to help promote the new modernising imperial Meiji regime.

Until the 1870s the most widespread and popular public images of famous people in Japan had been pictures of kabuki theatre stars, in the form of woodblock prints. Pictures of male actors, playing male or female roles, were collected by their loyal fans. Actor prints in fact formed about 80 to 90% of the market for hand produced full colour woodblock prints. Photographers soon saw the commercial possibilities of producing large runs of actor images. The invention of photography was a threat to woodblock print artists and their publishers.

Printmakers and artists responded in various ways to the competition of photography. Some actually designed prints that tried to imitate the black and white or sepia colouring of photographs, while others adopted more imaginative approaches.

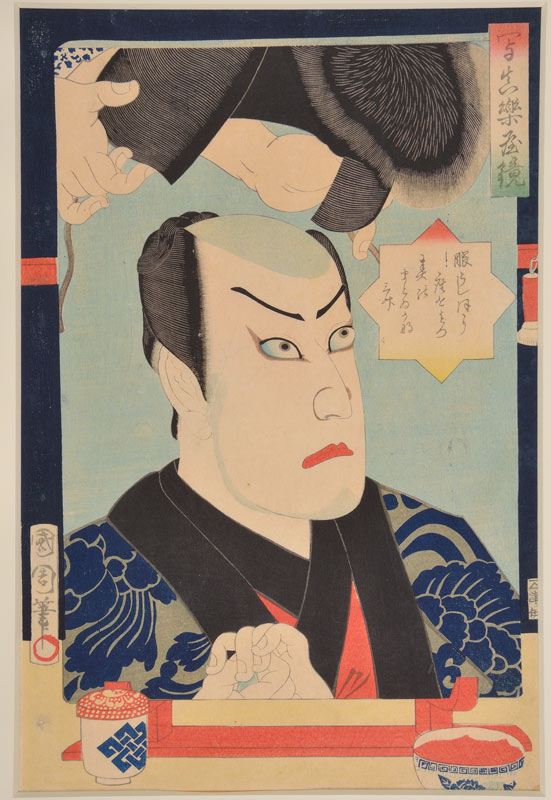

This 1868 print for instance is of Danjuro IX - a kabuki actor who had rockstar status and a huge fan following. It is from a series of hand cut hand printed images entitled ‘Mirror of Photographic Likenesses of Backstage Actors’. Of course it is not a photographic likeness at all, far from it. It is a highly stylised and traditionally rendered woodblock image of a face.

However the point being made is that this print is better than a photograph, as it offers the devoted fan a close-up intimate image with the actor sitting at his dressing room mirror. Ask any starstruck fan what they crave above all else and being present in the dressing room, where they could share a private moment with their hero, would be high up their list. Intimacy is the dream.

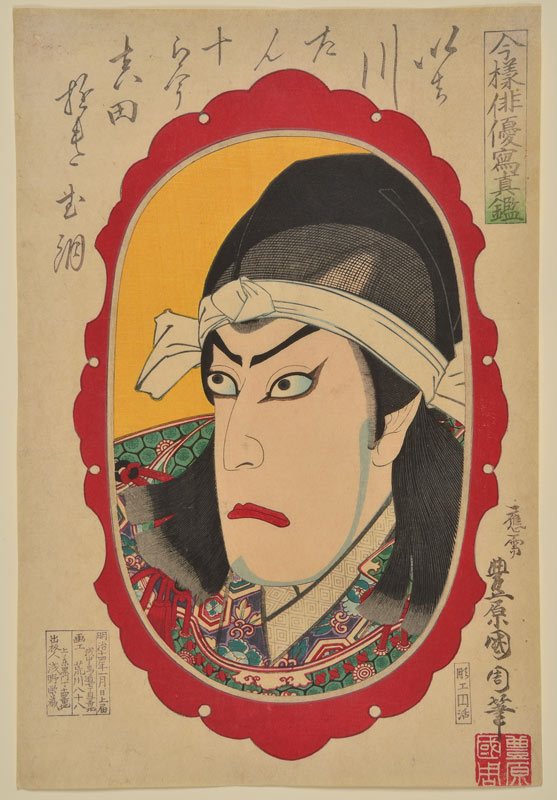

This image, also of Danjuro IX sitting in front of his mirror, is from a print series which makes an even more deliberate suggestion of its pictorial superiority to a photograph. The series is called ‘Modern People in Photographic Style’ and the oval laquer wooden frame surrounding Danjuro's face is of a type used to frame photographs at the time. It is also in full colour, which makes it far superior to photographs of that era.

Perhaps the most adventurous response to the commercial threat posed by photography and other mechanical reprographics was to play to the existing strengths of the woodblock itself. Prints like this one from 1895, again showing Danjuro IX, use three sheets of paper to give an almost cinematic widescreen close-up image of the star in in one of his most famous roles. Not surprisingly, this is regarded as one of Kunichika's best prints.

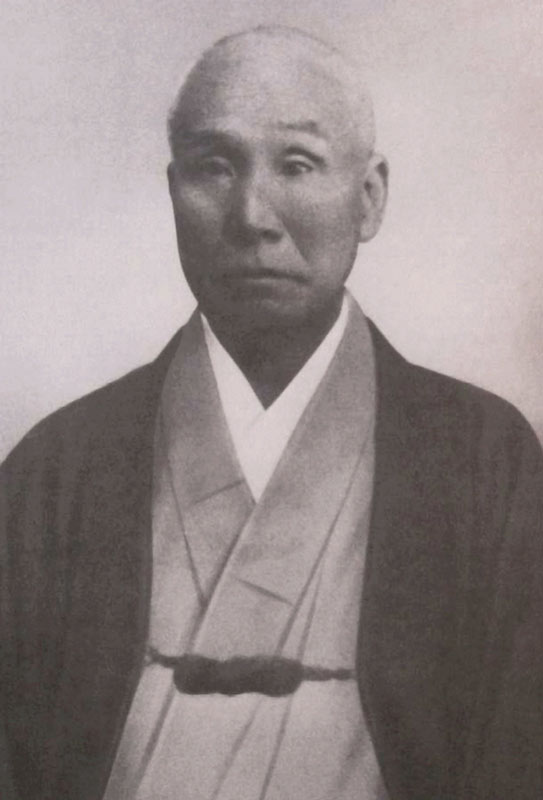

What Kunichika himself thought of photography is not recorded. He did have a close family connection with the new process though, as his brother ran a photographic studio during the 1890s. That is probably why, of all the leading Japanese print artists of the 19th century, Kunichika is the only one we actually have a photograph of.

This photograph of Kunichika was made three years before his death, around 1897. He looks rather serious and, in my opinion, perhaps just a little disapproving of this new form of portraiture.

All images of Kunichika prints © National Museums Liverpool, courtesy of Frank Milner. These prints are all on display in the exhibition Kunichika: Japanese Prints at the Lady Lever Art Gallery, 15 April - 4 September 2022.