Getting to know Edward Lear… on his own terms

As part of Pride Month, we are taking a looking back at the life of 19th century poet and painter Edward Lear. His lively work reveals something of his (often unrequited) loves and his penchant for pushing boundaries through lively language and absurd imagery.

How pleasant to know Mr.Lear

Who has written such volumes of stuff

Some think him ill-tempered and queer

But a few think him pleasant enough…

(Edward Lear, The Complete Nonsense Book, 1912)

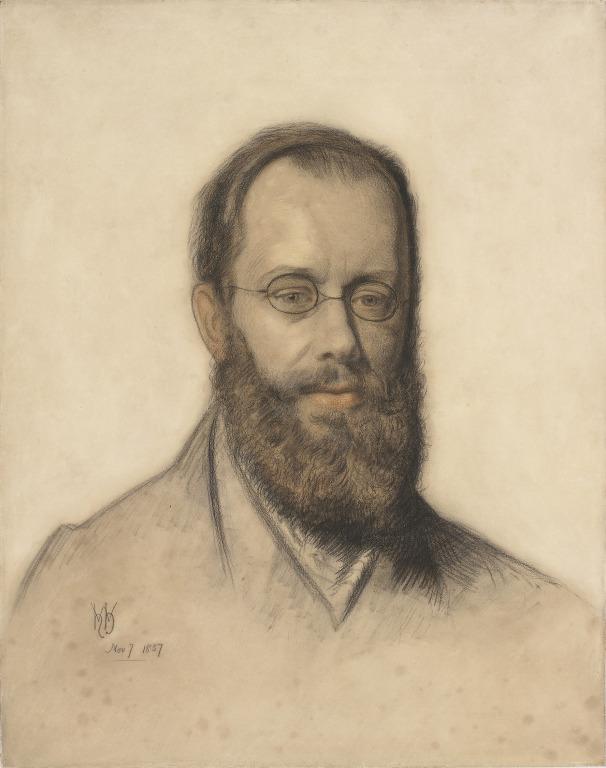

Edward Lear (1812-1888) is famous for his much-loved nonsense poems, including The Owl and the Pussycat. He was also a landscape painter, scientific illustrator, travel writer, musician and composer. His paintings of zoological specimens at Knowsley Hall also link him to the collections here at National Museums Liverpool (more on that below). Lear’s many interests, talents and charms endeared him to some of the most influential politicians, artists and writers in England during his lifetime. His legacy lives on in his paintings and poetry, which are still enjoyed by many to this day. Edward Lear’s story also has contemporary resonance. His life and work reveal something of his (often unrequited) love of other men and his penchant for pushing boundaries through lively language and absurd imagery.

The Owl and the Pussy-Cat went to sea

In a beautiful pea-green boat:

They took some honey, and plenty of money

Wrapped up in a five-pound note.

The Owl looked up to the stars above,

And sang to a small guitar,

"O lovely Pussy, O Pussy, my love,

What a beautiful Pussy you are,

You are,

You are!

What a beautiful Pussy you are!"

Unlikely Pairings and Nonsense Poetry

In 2014, The Owl and the Pussycat was voted Britain’s most beloved children’s poem. In the famous rhyme, our unlikely duo – the eponymous owl and pussycat – elope in a their pea-green boat, serenading one another under the stars. Lear delighted in absurd pairings. In one of his best-known limericks, we find “an Old Man of Whitehaven” dancing “a quadrille with a Raven”. These strange bedfellows are partly a product of the ridiculous results of rhyming words like “raven” and Whitehaven”.

As is often the case with Lear, however, there is more than meets the eye. Throughout his life, Lear was seen as a figure of fun (and his sense of silliness did make him stand out in the social circles he moved in). However, Lear often felt different and somewhat apart from the people around him. In letters to his friends, he described episodes of this social anxiety as “the darks”. Lear was epileptic, which he kept secret from even his closest confidants. He also had a number of unrealised romantic attachments to other men.

We don’t know how Lear understood his own sexuality or whether he was ever open with others about it. But in this light, the genderless and unlikely pairing of the owl and pussycat might take on new meanings. His sense of being different can also be read in his poems through references to a judgmental ‘they’, anonymous people who seek to squash any behaviours beyond the apparent norm. Our dancing old man of Whitehaven, for example, is “smashed” for his indiscretions.

There was on Old Man of Whitehaven

Who danced a quadrille with a Raven;

But they said, “It’s absurd to encourage this bird!”

So they smashed that Old Man of Whitehaven.”

From his diaries, we know of Lear’s love for the young barrister Franklin Lushington, who he met during his travels as a landscape painter in Malta in 1849. In one passage, he agonises over his unrequited feelings, describing them as “a fanatical… frantic caring overmuch for those who care little for us”. Lear’s diaries don’t tell us whether Lushington was aware of his friend’s romantic longings. However, as the executor of Lear’s will, Franklin Lushington destroyed Edward’s diaries covering the years of their close friendship during their time in Greece and Malta up to 1858.

Watercolour sketch by Edward Lear in Malta, May 1862

Natural Sciences and the Order of Things

Edward Lear’s playful personality and his non-conformity also comes through in his earlier career as a painter and illustrator for natural scientists.

As a young man, Lear spent a lot of time with his sisters who were responsible for his upbringing and education. The Lears were an influential family in the London trades and guilds, making money on the stock exchange, as well as importing and re-exporting raw sugar sourced from slave plantations in Jamaica (something Lear chose to ignore in his writings and diaries). Lear claims to have been one of 21 children and he was sent to live with his oldest sister Ann at the age of four. His siblings taught him how to draw, paint and play music.

Despite suffering from vision problems, Lear showed immense talent for detailed drawing and illustration. Even as a boy, he was commissioned to paint posters for medical professionals and coloured painted screens, fans and prints for clients. Lear had to rely on his artistic abilities as he was, in his own words, “turned out into the world, literally without a farthing – and with naught to look to for a living but [my] own exertions”.

Lear’s education also exposed him to the explosion of interest in botany and ornithology, which had blossomed in England following the voyages of Captain Cook in the 1760s. Wealthy individuals funded trips to collect exotic species of plants, birds and reptiles from across the globe. There was a race to identify, label and discover new specimens and place them in neat categories, such as the model created by Carl Linnaeus’ (1707-1778) for grouping flora and fauna.

Macrocercus Aracanga (Red and Yellow Macaw) by Edward Lear (1832)

Combining his love of drawing with a growing interest in the natural sciences, Lear started taking commissions from leading figures in the field of Zoology. He created plates for scientific publications and produced his own book Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots (1832). It was his interest in parrots and painting animals from life that brought Lear to the attention of Lord Stanley, who would later become the 13th Earl of Derby. The Earl became Lear’s greatest support and patron.

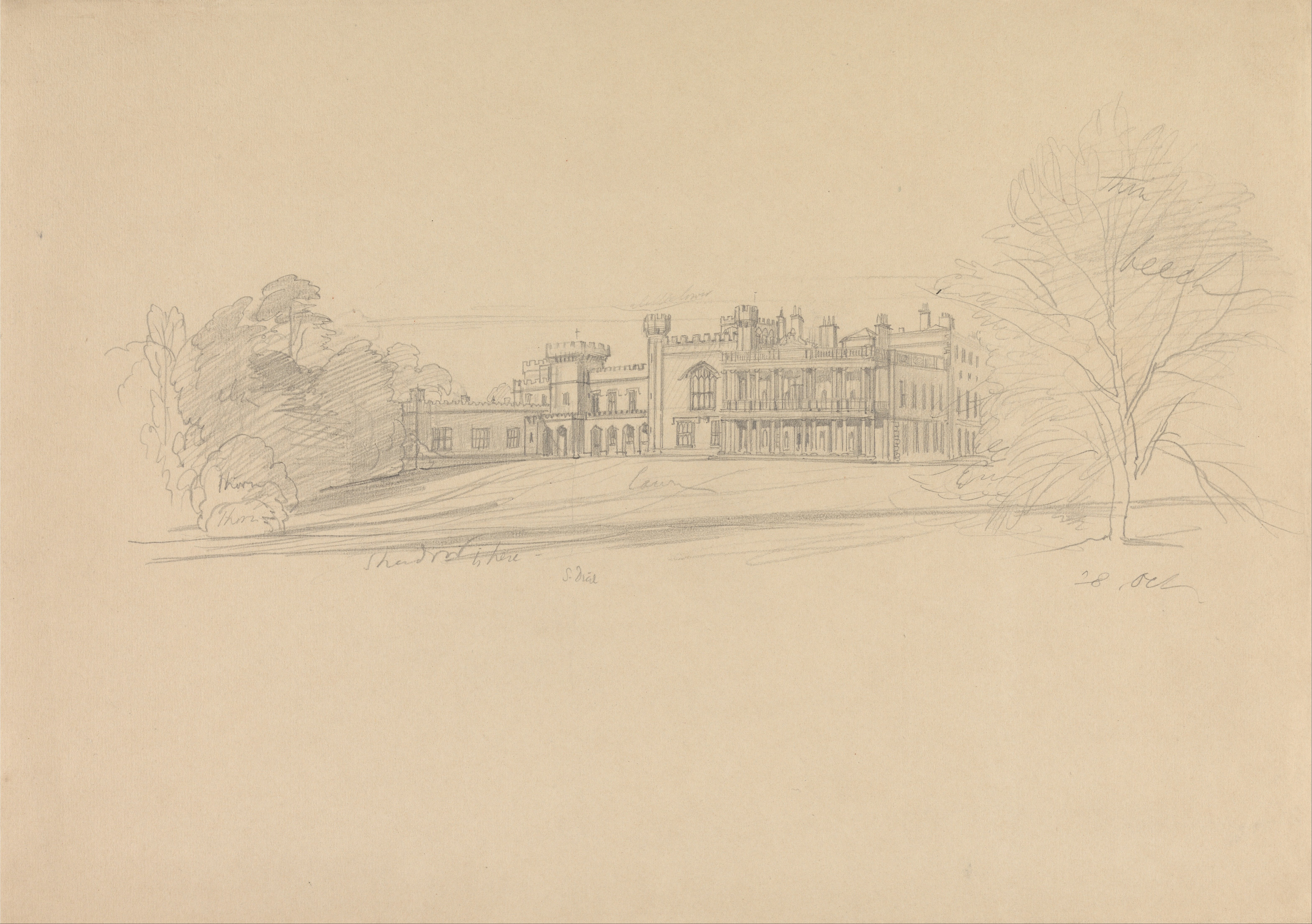

Lear was commissioned to paint the live (and dead) zoological specimens amassed at Knowsley Hall in Liverpool. The estate was owned by The Earl of Derby, a prominent English politician and natural science enthusiast. In 1851, the Earl donated thousands of animal skins from Knowsley to the city of Liverpool which became the founding collection of the World Museum. Many of these specimens had been painted and documented by Edward Lear. It was during Lear’s intermittent residency at Knowsley (between 1831-7) that he first composed his nonsense poems for the children of the estate.

Pencil Sketch of Knowsley Hall, Liverpool by Edward Lear

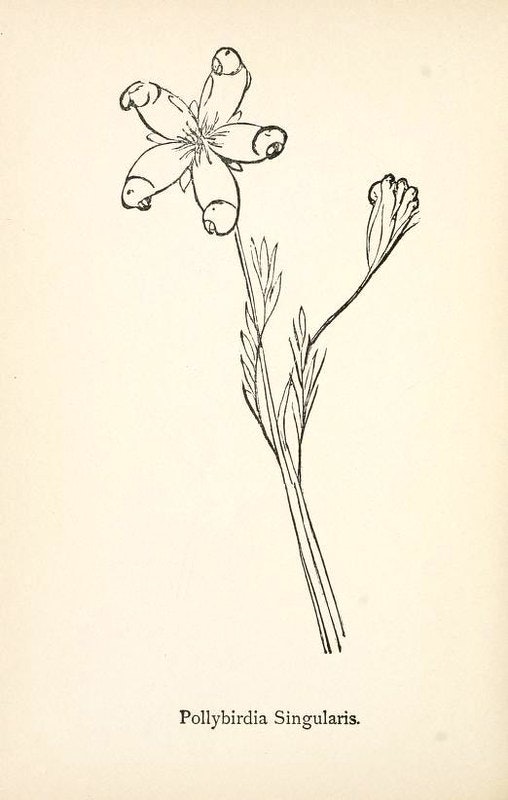

Playing with Categories

Lear’s interest in the natural sciences inspired him to play with the very idea of categories. In his Nonsense Botany (1877), Lear created illustrations of unbelievable flora which poked fun at the long tradition in the natural sciences to identify new species with long Latin names. Lear’s creations, such as the Tickia Orologica (a plant with tiny clock flowers) or the Pollybirdia Singularis drew inspiration from this scientific tradition. His drawings might also be read as a challenge to the Western tradition of collecting and categorising the world around us.

Pollybirdia Singularis by Edward Lear

In The Scroobius Pip, a poem that was left unfinished when he died in 1888, Lear leaves us with another bold and improbable character. The Scroobius Pip is an unclassifiable beast that defies classification. Despite the attempt of other creatures to pigeon hole them at every opportunity, they self-confidently (or unwittingly) reply, “My only name is the Scroobius Pip”.

The Scroobious Pip went out one day

When the grass was green, and the sky was grey.

Then all the beasts in the world came round

When the Scroobious Pip sat down on the ground.

The cat and the dog and the kangaroo

The sheep and the cow and the guineapig too--

The wolf he howled, the horse he neighed

The little pig squeaked and the donkey brayed,

And when the lion began to roar

There never was heard such a noise before.

And every beast he stood on the tip

Of his toes to look a the Scroobious Pip.

At last they said to the Fox - "By far,

You're the wisest beast! You know you are!

Go close to Scroobious Pip and say,

Tell us all about yourself we pray-

For as yet we can't make out in the least

If you're Fish or Insect, or Bird or Beast."

The Scroobious Pip looked vaguelyy round

And sang these words with a rumbling sound-

Chippetty Flip; Flippetty Chip;-

My only name is the Scroobious Pip.

Like the Scroobius Pip, so much of Lear’s emotional life and work is rich and complex and difficult to place within neat boundaries. Following Lear’s lead, surely it is far more rewarding to understand people and things on their own terms.

Further Reading

Fisher, Clemency (2002) A Passion for Natural History: The life and legacy of the 13th Earl of Derby

Lodge, Sara (2019) Inventing Edward Lear

McCracken Peck, Robert (2021) The Natural History of Edward Lear

Swaab, Peter (2016) ‘Some Think Him…Queer’: Loners and love in Edward Lear in: Williams and Bevis (eds.) Edward Lear and the Play of Poetry

Uglow, Jenny (2017) Mr Lear: A life of art and nonsense