The Innocents - lost at sea

2021 marks the 81st anniversary of the sinking of the Children's Ship, the City of Benares. Torpedoed in the North Atlantic, more than 600 miles from land, with 90 evacuee children on board, the tragedy still has echoes today.

Ellerman Line ship, SS City of Benares, after she’d been requisitioned for war service

"City of Benares, Ark of Salvation from nightmare nights of flame; For all the terrors that sent them away The Innocents bear no blame."

These words form the refrain of The Innocents, a new work for organ and choir by composer Patrick Hawes and librettist Andrew Hawes. Commissioned by Proms at St Jude’s to mark the 80th anniversary of the sinking of the SS City of Benares last year. This piece was originally intended to premier in 2020 but, as with so many other things, Covid-19 forced a change of plan and sadly it is yet to be performed.

The loss of 'the Children's Ship'

The church of St Jude-on-the-Hill has a powerful connection with this tragedy. The son of the then vicar, William Maxwell Rennie, was lost in the disaster. Michael Rennie was just 23 years old and had volunteered as an escort in the CORB scheme. This scheme was designed to evacuate British children overseas in the Second World War, sending them to safety in Canada, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand. It was aimed at the children of those who could not afford private passage and, despite the threat from the U-Boats, it was wildly popular. The City of Benares though would be almost the last of these ships, and the reason for the scheme’s abrupt end.

At 10pm on 17 September 1940, after 4 days at sea, the City of Benares was fatally hit by a torpedo. There were 406 people on board, including 90 evacuee children aged between 5 and 15. With 90 children torpedoed 600 miles from land, in a storm at night, the incident unfolded just as tragically as you might assume. The lifeboats launched badly, becoming swamped by the waves, children were lost into the dark sea and those that managed to remain in the flooded boats were sat in freezing water. Michael Rennie dived again and again into the sea trying to save the children in his care, heedless of his own well-being. Sadly, his exertions on the children’s behalf ultimately came at the cost of his own life.

Memorial to Michal Rennie in St Jude’s Church, painted by Walter Starmer. © The Parish Church of St Jude-on-the-Hill

Alerted to the City of Benares’ distress call, the HMS Hurricane raced through the night, forced to balance the need for speed with the knowledge that if they sank in the storm then there would be no one to rescue the Benares survivors. They arrived the following afternoon to scenes of devastation, and there were only 7 of the CORB children amongst the survivors they were able to rescue. A further 6 children and 39 adults were subsequently picked up alive in a lifeboat, that had drifted far from the sinking, 8 days later. The final death toll was 258 - 77 of those lost were evacuee children.

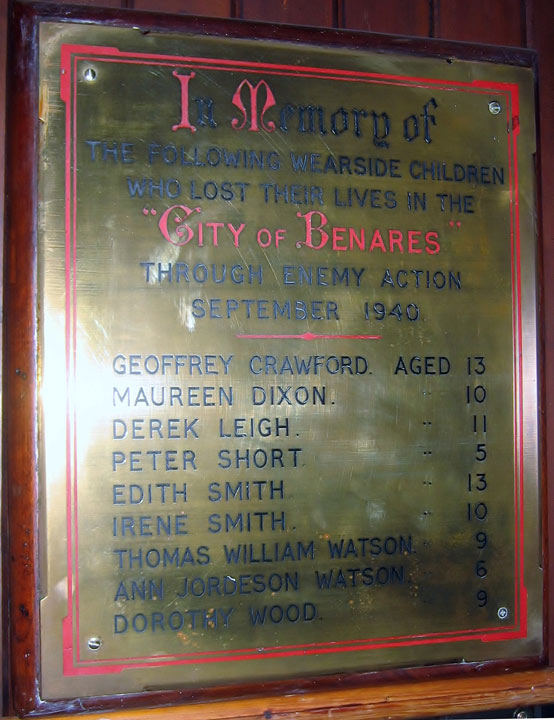

The evacuee children were from Britain’s industrial cities, like Liverpool and Sunderland, where this memorial plaque is from, bearing the names of local children lost in the sinking.

Counteracting horror with beauty

There are perhaps few more difficult things to address than the death of children on such a scale. Andrew Hawes described writing the words for The Innocents as:

"...one of the most difficult things I’ve had to do by way of commission... the subject is unremittingly dark."

I could easily identify with that. The City of Benares is the most difficult subject I’ve ever written about, and one that stays with you long after you put down your pen. It seems very fitting to me that a tale as haunting as this one should be commemorated in a choral piece, the human voice being perhaps the most haunting of instruments. Patrick Hawes said he chose to pair the choir with the organ, because he felt the organ was, appropriately, evocative of the sea. We’re yet to hear the music, but if Patrick’s other works are any indication, it will be well worth waiting for. Andrew’s lyrics though can be read on Patrick Hawes’ website.

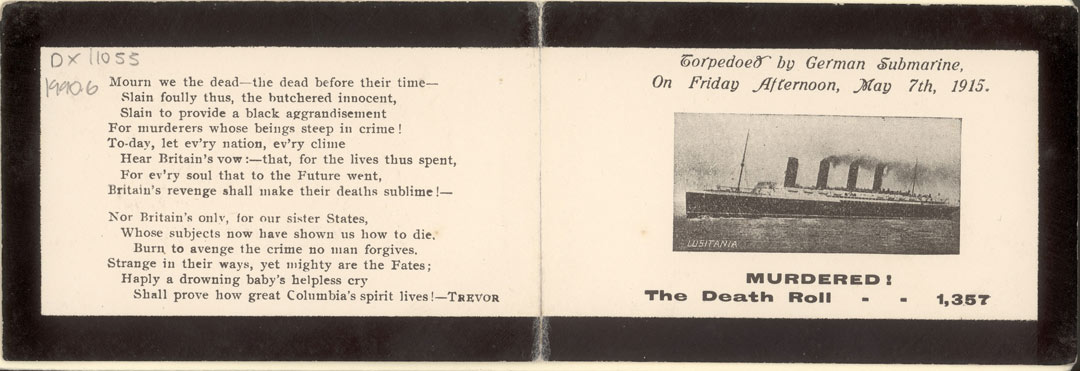

In talking about his composition and working with his brother’s lyrics, Patrick Hawes also acknowledged what a difficult subject this is, that it is hard to find any light or joy amongst the terror and loss. He said though that he wanted the horror to be “counteracted with a feeling of beauty.” Whilst it can feel hard to think about creating beauty from tragedy and horror, it’s an idea we see repeatedly used to great effect in war art and poetry. Indeed, the lyrics for The Innocents do read rather like a war poem. In fact, they reminded me of some other poems commemorating major sinkings that we have in the Maritime Museum collections. In particular they brought to mind one written in response to the wartime sinking of the Lusitania, another tragic loss to the U-boats in a previous conflict.

Lusitania memorial card with poem, from Maritime Archive collections – DX/1055/5/5a

Both Andrew’s lyrics and our Lusitania poem refer to innocents, but there is a clear difference in tone. The Lusitania poem was written shortly after the sinking and its use of the word “innocent” is meant to stir emotions of anger and vengeance.

"Slain foully thus, the butchered innocent,

Slain to provide a black aggrandisement

For murderers whose beings steep in crime!"

In The Innocents we see commemoration at a remove of 80 years, allowing a more objective view. The blame here is not laid on the Germans who fired the torpedo, but the wider ideas of greed and pride that are, so often, at the route of conflicts that inevitably harm most those who are already the most vulnerable.

While telling the story of the City of Benares, The Innocents also carries this wider theme of children’s experiences in war and conflict. For many people today, the City of Benares story tends to call to mind images not of the Second World War but of something very much closer, something we have all become sadly accustomed to seeing on the news; the loss of so many lives of those trying to make difficult and dangerous sea crossings in search of a better, safer life for their children. Patrick Hawes himself talks about “finding a resonance, finding an anchor, in contemporary accounts, and visual records on the news, of refugees today.” Innocents fleeing conflict are still being lost at sea.

Recent echoes

When it comes to memorialisation there’s always one very difficult question to answer, when do we stop commemorating something? I’ve been writing about the City of Benares since the 75th anniversary back in 2015, and with the 80th having passed last year I wondered if that was a good time to stop. Then I read about the delayed premier of The Innocents and saw some wonderful interviews with those involved, and decided it wasn’t quite time yet.

I suppose, as a historian, I personally think that we can stop commemorating an event when as a society we’ve learnt all there is to learn from it. Patrick Hawes’ words reminded me that we have not yet sufficiently learnt from this tragedy.

After a summer in which debate was raised by some about the legitimacy of a charity, specially founded to save lives at sea, rescuing migrant children in the Channel, I think it is clear we still have a long way to go. Heartening as it is to see most people do not think like that, whilst there are a vocal minority who can accuse the RNLI of facilitating illegal immigration, it remains essential that we remember Britain’s own children have been the refugees in search of safety.

Waterline model of RNLI lifeboat from the Maritime Museum collections – 1966.33.3

As an aside at this point, it is also well worth remembering that the RNLI are staffed by volunteers, people who will turn out of their beds in the middle of the night to try and save the lives of those they have never met. People who encounter traumatising things as a result. One volunteer who’d been to the aid of migrants in distress said:

"The children are normally terrified, screaming and crying. We need to help. No-one deserves to drown because of where they come from."

BBC News, 28 July 2021

That that needs saying is frankly harrowing. In short, I’m afraid I must argue that until we stop seeing fleeing children lost like this, and more particularly stop seeing the lives of vulnerable people used as a political football, the City of Benares will always have something to teach us. There is no difference in the terror felt by migrant children today and that felt by those CORB evacuees who lost their lives 81 years ago. Almost a century on, the story of the City of Benares serves to provide a visceral reminder, well-phrased in Andrew Hawes’ lyrics, that:

"Innocents pay the price for greed and pride."