Journeys, Memory and Connection

This is the third in a series of articles on the theme of language, coordinated by National Museums Liverpool’s Ethics Group. Each article considers a different ethical concern in the way we use language within museums and galleries.

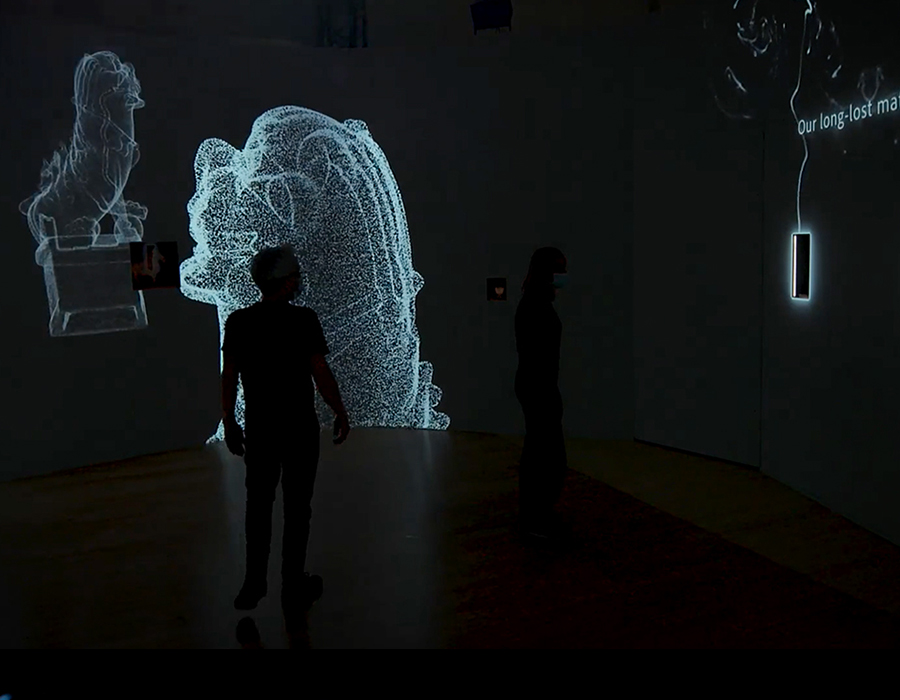

I, Too, am a Survivor is an immersive display of Chinese ceramics and forms the first of several interventions within the World Museum’s World Cultures gallery that aim to provoke new ways of thinking about our collections. National Museums Liverpool’s Ethics Group interviewed Lucy Johnson, Head of Art Gallery Exhibitions, on how language was at the heart of this new display.

How has language underpinned the new display?

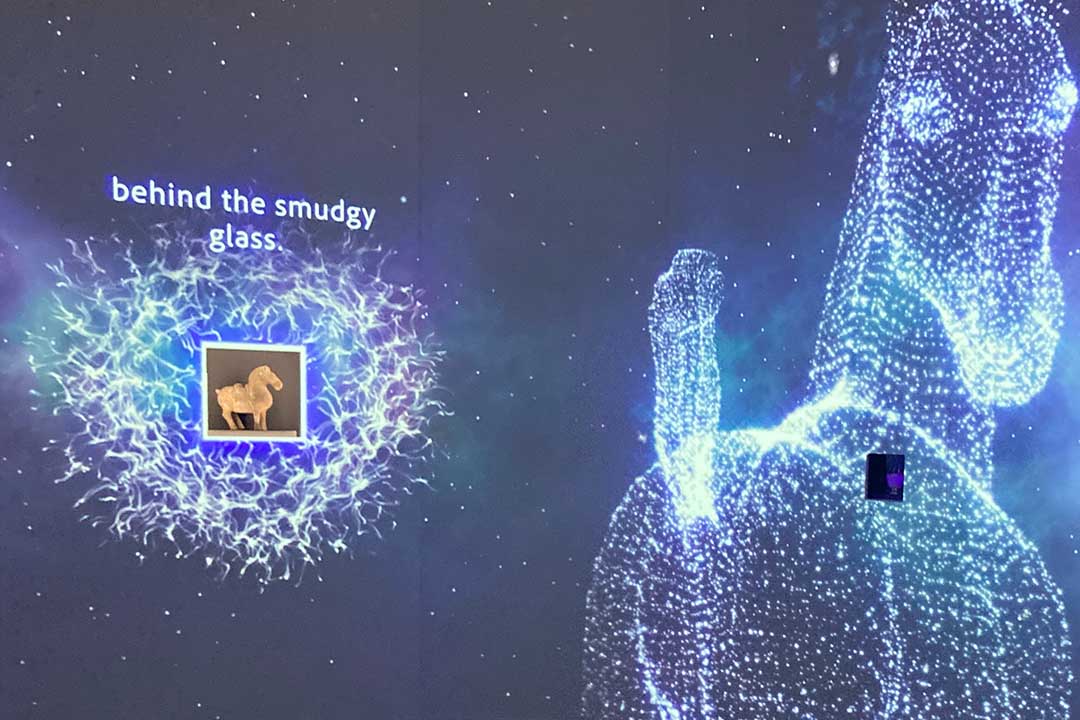

Sarah Howe’s beautiful and evocative poetry is central to the storytelling in this display. This creative response to seven Chinese ceramics allows us to imagine the objects’ pasts and gives them an identity which we can connect with on an emotional level. The poetry has inspired the mesmerising and captivating projections which create an immersive and engaging experience, bringing the objects to life.

Why is language important?

Language is important in everything we do. How we connect with each other, the way we present ourselves, what it says about who we are and how we are perceived by others. Within the museum, the language we use can be a way to engage with new audiences, to tell stories and share histories, but at the same time has the potential to create barriers and alienate people. It affects how visitors view what the museum does, who we are here for, and the stories we tell.

At the start of the Where Next project, we asked visitors to respond to various questions about ideas around culture, identity and the displays in the World Cultures gallery. One reoccurring theme in the responses was ‘difference’ and it illustrated how the displays were perpetuating the idea that culture is solely defined by where someone comes from. The language in the gallery played a big part of this in terms of how we speak about objects and the places where they were made, through a narrow perspective. We want the new displays to be a move away from highlighting difference and to explore wider issues which unite and connect us.

What voices are presented in this display?

Usually, we hear the museum’s voice in displays. Through the Where Next project, we want to address the lack of voices from the communities that the gallery claims to represent. We intend for the new displays to give a platform to voices from outside of the museum and to bring different perspectives to the gallery. In I, Too am a Survivor, we hear Sarah Howe reading her poems – an imagined world inspired by the objects’ journeys, but also echoing Sarah’s own experience of being a Hong Kong born British citizen and her migration to the UK. We have also worked with a wide range of creative partners to bring the visual content to life and this process has been key in providing a different perspective to the objects’ histories. Public consultation enabled our visitors to contribute to this too.

How does the poetry in the display contribute to the understanding of the objects?

The poetry gives us a new and fresh way to think about the objects. To imagine their journeys. To feel their experiences and empathise with their emotions. It allows us to understand the objects through their encounters of change, displacement, transformation and belonging – topics that we can all connect with on some level. The horse longing for home, the fear and distress of the Kraak dish caught in a storm at sea, the longstanding friendship between the two lion incense burners. Our ceramic protagonists, and their journeys halfway around the world, can show us something about what it is to be human.

I, Too, am a Survivor began as a collaboration between the museum and the TIDE project at the University of Liverpool where Sarah Howe was the poet-in residence in 2018. Other creative partners included Belle Vue Productions, Birkenhead High School, LJMU School of Art and Design, Urban Projections and Meaningful Magic.

This article is the final in a series exploring the theme of language in museums. You can read the other articles in this series below.