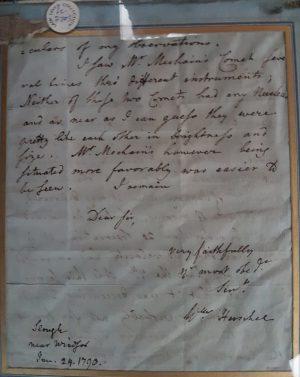

A letter from William Herschel

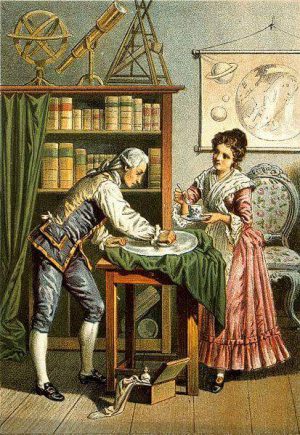

1896 Lithograph of William and Caroline Herschel grinding a telescope mirror. Caroline is supplying the grinding paste from the tea cup - not tea!

Lord Leverhulme was a collector in the broadest sense of the word, known for his collections of Victorian paintings, sculpture, eighteenth century furniture, tapestries, Wedgwood jasperware and Chinese ceramics. In his collection at the Lady Lever Art Gallery there are also fascinating historic documents which he collected.

In light of International Women's Day on 8 March we have been enjoying a beautifully written letter which has brought into focus the life of a remarkable woman of science who lived in the eighteenth century. The woman is Caroline Lucretia Herschel, sister to the better known William Herschel (1738-1822), Royal Astronomer to George 3rd. William shot to fame when he discovered the planet Uranus in 1781 from his home in Bath. He used a telescope he had designed and constructed himself.

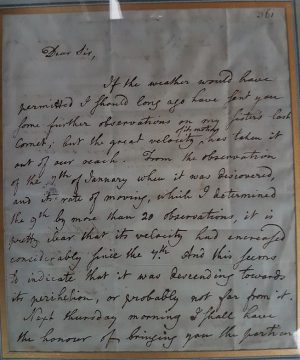

Caroline (1750-1848) developed an interest in astronomy and assisted William in his work, charting and recording details of his astronomical observations. In 1783 Caroline was given her own telescope and went on to discover and observe eight comets. The letter in our collection is from William Herschel to the Astronomer Royal, Rev Dr. Neville Maskelyne. It mentions Comet C/1790 A1 Herschel, which Caroline discovered on 7th January 1790 and later observed on the 10th and 15th January.

An account, written in 1784, describes Caroline working at home and gives some idea of how surprised the writer was to find a woman doing such work.

‘Instead of the master of the house, I observed, in a window at the further end of the room, a young lady seated at a table, which was surrounded with several lights; she had a large book open before her, a pen in her hand, and directed her attention alternatively to the hands of a pendulum- clock, and another dial placed beside her, the use of which I did not know: she then noted down her observations.

“My brother, “said Miss Caroline Herschel, “has been at work these two hours; I do all I can to assist him here. That clock gives me the time, and this dial, the hand of which communicates by strings with his telescopes, informs me, by signs which we have agreed upon, of whatever he observes. I mark upon that large chart the stars which he enumerates, or discovers in particular constellations, and even in the most distant parts of the sky….” ‘

1896 Lithograph of William and Caroline Herschel grinding a telescope mirror. Caroline is supplying the grinding paste from the tea cup - not tea!

Lord Leverhulme was a collector in the broadest sense of the word, known for his collections of Victorian paintings, sculpture, eighteenth century furniture, tapestries, Wedgwood jasperware and Chinese ceramics. In his collection at the Lady Lever Art Gallery there are also fascinating historic documents which he collected.

In light of International Women's Day on 8 March we have been enjoying a beautifully written letter which has brought into focus the life of a remarkable woman of science who lived in the eighteenth century. The woman is Caroline Lucretia Herschel, sister to the better known William Herschel (1738-1822), Royal Astronomer to George 3rd. William shot to fame when he discovered the planet Uranus in 1781 from his home in Bath. He used a telescope he had designed and constructed himself.

Caroline (1750-1848) developed an interest in astronomy and assisted William in his work, charting and recording details of his astronomical observations. In 1783 Caroline was given her own telescope and went on to discover and observe eight comets. The letter in our collection is from William Herschel to the Astronomer Royal, Rev Dr. Neville Maskelyne. It mentions Comet C/1790 A1 Herschel, which Caroline discovered on 7th January 1790 and later observed on the 10th and 15th January.

An account, written in 1784, describes Caroline working at home and gives some idea of how surprised the writer was to find a woman doing such work.

‘Instead of the master of the house, I observed, in a window at the further end of the room, a young lady seated at a table, which was surrounded with several lights; she had a large book open before her, a pen in her hand, and directed her attention alternatively to the hands of a pendulum- clock, and another dial placed beside her, the use of which I did not know: she then noted down her observations.

“My brother, “said Miss Caroline Herschel, “has been at work these two hours; I do all I can to assist him here. That clock gives me the time, and this dial, the hand of which communicates by strings with his telescopes, informs me, by signs which we have agreed upon, of whatever he observes. I mark upon that large chart the stars which he enumerates, or discovers in particular constellations, and even in the most distant parts of the sky….” ‘

Herschel's letter from 1790 (front)

For her work in assisting her brother Caroline received an annual salary of £50 from the King, making her the first woman in England to receive a government position. William died in 1822 but Caroline continued their work and in 1828 and was awarded with a gold medal by the Astronomical Society of London (Royal Astronomical Society).

Along with Mary Somerville, she was named an Honorary Member of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1835. They were the first two women to be admitted to the Society. Although Caroline had received a fairly rudimentary education when she was a child she went on to become one of the most respected and honoured astronomers. Quite an achievement for a woman of her time and she is immortalised by having a crater on the moon and an asteroid named after her.

Herschel's letter from 1790 (front)

For her work in assisting her brother Caroline received an annual salary of £50 from the King, making her the first woman in England to receive a government position. William died in 1822 but Caroline continued their work and in 1828 and was awarded with a gold medal by the Astronomical Society of London (Royal Astronomical Society).

Along with Mary Somerville, she was named an Honorary Member of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1835. They were the first two women to be admitted to the Society. Although Caroline had received a fairly rudimentary education when she was a child she went on to become one of the most respected and honoured astronomers. Quite an achievement for a woman of her time and she is immortalised by having a crater on the moon and an asteroid named after her.

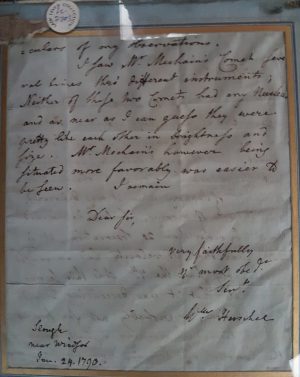

Herschel's letter (back)

Herschel's letter (back)