Liverpool and Benin, a Global Story

How are the histories of Benin and the port city of Liverpool interconnected?

Although bronze and ivory works from Benin City in Nigeria are admired by visitors to our World Cultures Gallery from around the world, their presence in World Museum has a violent history. Curator of African Collections Zachary Kingdon shares part of this history to show how Liverpool’s relationship with Benin is part of a wider global story.

Benin’s brilliant royal inheritance of commemorative altar pieces and other artworks was dismantled and stolen following the British colonial conquest of the Edo Kingdom in 1897.

The outline of this fraught history is widely known.

A British military force was sent to take over the Edo Kingdom after a party of nine colonial emissaries and their 200 African carriers were ambushed while on their way to visit Oba Ovonramwen, the reigning monarch. The leader of this unfortunate party, James Phillips, Acting Consul-General of what the British called the Niger Coast Protectorate in southern Nigeria, had ignored Oba Ovonramwen’s insistence on a postponement of their visit to Benin City. The ambush was carried out by an Edo military force led by a number of titled chiefs which succeeded in killing most of the British party. Britain’s response in sending a military ‘expedition’ in February 1897 that ransacked the Oba’s palace and took over the Edo Kingdom was presented as a punishment for the killings, but it fulfilled a long-held aim of the British government to break the Oba’s control over Edo markets and resources. After the imposition of colonial overrule, the Edo Kingdom, long imagined to be an ‘El Dorado’ of tropical forest products like palm oil, rubber and timber, was opened up to botanical prospecting and commercial exploitation by British trading firms.

While this outline of events is now well known, Liverpool’s part in the broader history that frames these events is less recognized. How are the histories of Benin and the port city of Liverpool interconnected?

To begin with, Liverpool trading firms active in southern Nigeria had been impatient for a military solution to what they saw as the Oba of Benin’s obstruction to their ambitions. James Pinnock, for example, founder of James Pinnock & Co., had written in 1895 to the Consul-General for the Niger Coast Protectorate calling for the Oba of Benin to be ‘deposed or transported elsewhere’ so that the natural wealth of the Edo Kingdom could be opened up for British commercial exploitation.

Collection records at World Museum, show that Liverpool’s municipal museum wasted little time in adding a group of looted items from Benin City to the museum’s West African collection from early in October 1897. The then director Henry Ogg Forbes purchased several more in December that year directly from Dr Felix Roth.

Dr Roth had served as surgeon to the Advance Guard with the British force that attacked and looted Benin in February 1897. Like many other British officers who participated, Dr Roth took a personal share of unofficial loot from the ransacked Benin palace complex. He must have transferred some of this loot to his brother Henry Ling Roth, who was a curator at the Bankfield Museum in Halifax, because in April 1898 Forbes purchased a further series of Benin items from Ling Roth. Forbes also helped to disperse looted works from Benin across the Atlantic by acting as an agent for the Field Columbian Museum in Chicago. He acquired several Benin bronzes for the Field Museum in 1899 from British dealers he was in contact with, and from whom he also purchased Benin works for the World Museum.

Not all Benin items acquired by the museum in the years immediately after the looting of the Oba’s palace were purchased from dealers or military personnel. For example, in April 1899 World Museum received a singular but significant gift from John Henry Holland of a mask-like hip ornament in brass from Benin. Holland, who had a family home at Thornton Hough on the Wirral Peninsula, was Curator of the colonial Botanic Station at Old Calabar in Southern Nigeria. He had returned to Britain in 1899 on training leave. This involved him in work at Kew Gardens, but it also included a five day visit to Merseyside during which he was shown round grain warehouses, timber yards, Toxteth Dock, the Bootle Jute Factory, the Liverpool Rubber Company, the African Oil Mills, the Sunlight Soap Works and the sample rooms of the general produce brokers Leete, Son, & Co. The visit was designed to gather information on Merseyside’s tropical plant-based industries so that his work in the Niger Coast Protectorate could be better tailored to serve the British economy.

Holland did not participate in the 1897 military action against Benin, so it’s not clear how he acquired the brass costume ornament that he gave to the museum in Liverpool. However, a number of other colonial officials based at Old Calabar did participate. Dr Robert Allman, the Niger Coast Protectorate Chief Medical Officer, was certainly one of them. Dr Allman took charge of the Botanic Station at Old Calabar when Holland made his trip back to Britain in 1899 and could have given Holland the costume ornament from Benin.

Liverpool’s role as a principal port of empire in the nineteenth century allowed many of its industries to prosper, while also helping its cultural institutions to develop. The city’s port also made it a hub for international travel and a destination for migrants and seamen from the colonies who contributed to a growing cosmopolitan citizenry. The late Dorothy Kuya (1933-2013), for example, was born and raised in a part of Liverpool settled by many Africans and Afro-Caribbeans, including seamen, servicemen, traders, professionals and students. A number of them were politically active in trade unions and the anti-colonial movement. Kuya’s Nigerian father had strong links to the anti-colonial movement and gave her a first-hand education in British colonialism in West Africa.

Kuya worked with Bernie Grant in the 1980s at the Haringey Council in London, before Grant was elected MP for Tottenham in 1987, and she joined the African Reparations Movement when Grant founded its UK arm in 1993. The Movement campaigned for an accurate portrayal of African history and cultures to help restore dignity and self-respect to dispossessed Africans and agitated for an apology from western governments for the enslavement and colonisation of African peoples. In 1996 Grant was contacted by Benin’s reigning monarch Oba Erediauwa, who requested assistance in a royal campaign to have bronze and ivory works held by British museums returned to Benin on the centenary of their theft due in 1997. Grant launched a fact finding mission and wrote to museums around Britain, including World Museum, requesting information about their Benin collections, but his campaign faced official obstruction and was unable to meet Oba Erediauwa’s hopes.

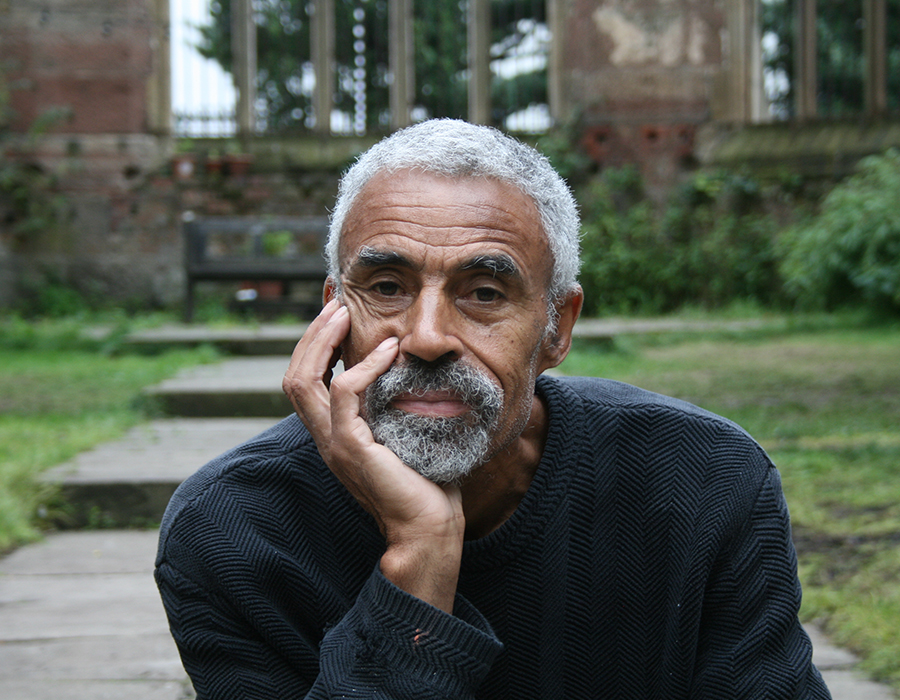

Tony Phillips, an artist born in Liverpool in 1952 to a father from Nigeria and an English mother, was raised in a highly diverse Liverpool neighbourhood and developed an awareness of how Britain’s colonial history was deeply etched into the fabric of the port city of Liverpool. In 1984 he created a striking series of twelve metal plate etchings on The History of the Benin Bronzes. The etchings provide a stark commentary on a cultural imperialism that denigrates and demoralises Africans and African cultures on the one hand, while on the other hand presenting African cultural creations, like the Benin bronzes, as things to be displayed for the amusement and admiration of art lovers in Europe and America.

As we approach the 125th anniversary of the British conquest of the Edo Kingdom and ransacking of Benin’s palace complex, Edo and Nigerian voices, along with their supporters, are keeping up calls for restitution and the return of Benin items in museum collections around the world to their rightful owners. A collaborative Benin Dialogue Group has been in existence for over 10 years with the aim of creating a new heritage infrastructure in Nigeria’s Edo State, namely the Edo Museum of West African Art, to receive rotating loans of Benin works from European museums. Recently, a few museums have committed to fully returning to Nigeria artworks in their collections that were looted from Benin’s royal court in 1897.

Through the Benin redisplay workshops, the gallery renovation, public events, online resources and partnership in other initiatives, World Museum aims to contribute to discussion on the future of museum collections of Edo court art stolen by British forces in 1897 and dispersed around the globe.

Head back to our main page to find out more.