LS Lowry and Rubbernecking | In focus

Rubbernecking is a universal phenomenon almost all of us will have found ourselves doing at some point in our lives. But what does it have to do with LS Lowry ? We take a closer look at his painting The Fever Van, on display at the Walker to find out.

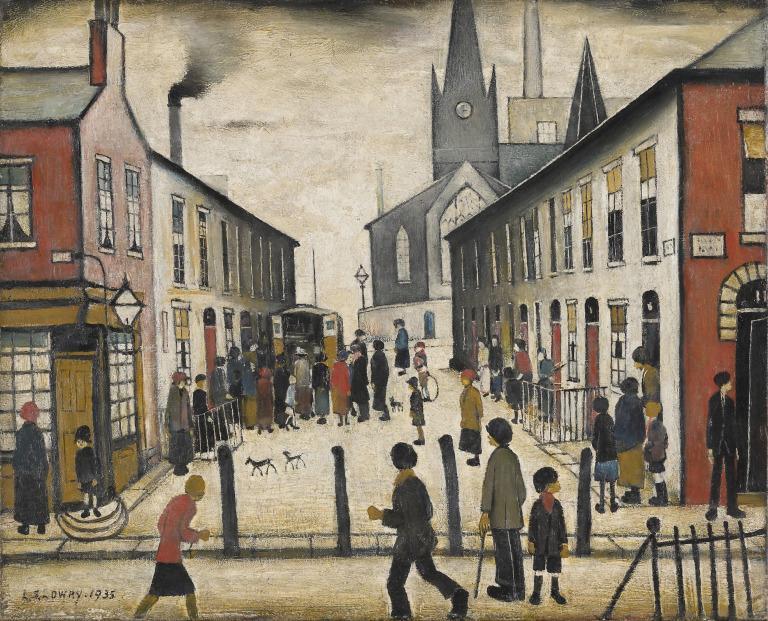

‘The Fever Van’ was painted in 1935 by Lawrence Stephen Lowry (1887-1976). It depicts an ambulance pulling up to a house to collect a fever patient. ’Fever Van’ is a colloquial term used in the North to refer to an ambulance that would transport patients with scarlet fever or diphtheria to the infectious diseases hospital. The van is surrounded by a crowd, gathered to look at what is going on. There are so many people, we can’t see the person being carried into the ambulance. Neighbours are at their front doors trying to see who is causing the drama, and in the foreground passersby are craning their necks to get a look at the situation. This composition is entirely intentional, Lowry didn’t necessarily want to show the emotion of the situation, but more how the urban environment reacts to it.

Accidents interest me - I have a very queer mind you know. What fascinates me is the people they attract. The patterns those people form, and the atmosphere of tension when something has happened… Where there's a quarrel there's always a crowd… It's a great draw. A quarrel or a body.

Lowry

We’ve all been there, whether it's peeking through your curtains to see what’s going on at the neighbours or trying to see what’s happened on the motorway when the police have closed a lane. Lowry has captured a questionable trait of human nature that we are all guilty of but rarely acknowledge or talk about.

So, what is it about the macabre that is so fascinating to us. Laurence Alison, Chair in Forensic and Investigative Psychology at the University of Liverpool explains why we can’t help but look when we see emergencies in real life.

I drove past a lorry on fire on the other side of the road this evening. A traffic jam had built up behind it. Even though there was no cordon our side and no accident, we had also come to a near standstill. Our traffic jam was created by a psychological ‘cordon’. Lowry’s [The] Fever Van captures this phenomenon admirably, with passers-by morbidly slowing down, craning their necks, and straining their eyes to see inside the van. This is known as ‘rubbernecking’.

What is the function of this evolutionary adaptive response? We know that animals often linger and prod their own dead family or herd members. Elephants, for example, are well known to find it hard to leave the rotting corpses of relatives and dolphins will seek to prop up fellow dolphins’ corpses long after death. Both elephants and dolphins are too smart not to realise that these friends and family members are dead. Moreover, these actions are not just about expressing sadness – they are not just about the bereavement process. Several theorists have argued for the more functional and adaptive process of elephants and dolphins physically ‘interrogating’ the corpses to learn what caused their demise.

Developmental psychologists have stated that children are fascinated by fictional violence and death at an early age to enable them to safely adapt to a more threatening world as they mature into adulthood. And it is well known that trying to bury trauma or totally ignore it can result in it gathering increased pressure until it becomes unbearable and then manifests in very damaging ways (post-traumatic stress disorder).In my own work with emergency services, police, and military I often ask personnel to engage in a process called ‘grim storytelling’. In order to prepare for major events, I ask them to construct worst-case scenarios. These then form the basis for their planning strategies should a terrorist event happen or, a large-scale fire or a mass shooting event. The 9/11 commission criticised the US’s response as a ‘failure of imagination’ and certainly a failure to consider the worst and hope for the best can be incredibly damaging for agencies whose role it is to protect the public.

As such, the phenomenon of rubber necking may be just one symptom of an adaptive function to safely engage with ‘what if it happened to me’ worst case scenarios. We all know these terrible events are mercifully rare, but should we be so unfortunate enough to find ourselves at the heart of one these, the opportunity for a series of short exposures to such traumas via rubbernecking may be an adaptive function. This then gets us ready and does not leave us naïve as to what they might sound, smell, and feel like.

According to Laurence Allison, Lowry’s painting is not as morose as we once thought. Instead it depicts the primordial desire in humans to survive by learning from one another. Taking a look at the painting once more with this in mind, the people surrounding the scene and craning their necks to get a look don’t appear as nosy and unfeeling as before. Instead, they look more desperate as they try to understand what has happened so that they can stop it from happening to themselves.