Lusitania and the world crisis

This is the sixth blog post in a series by J Kent Layton, maritime historian and author of 'Lusitania: an illustrated biography', to accompany the exhibition Lusitania: life, loss, legacy at the Maritime Museum.

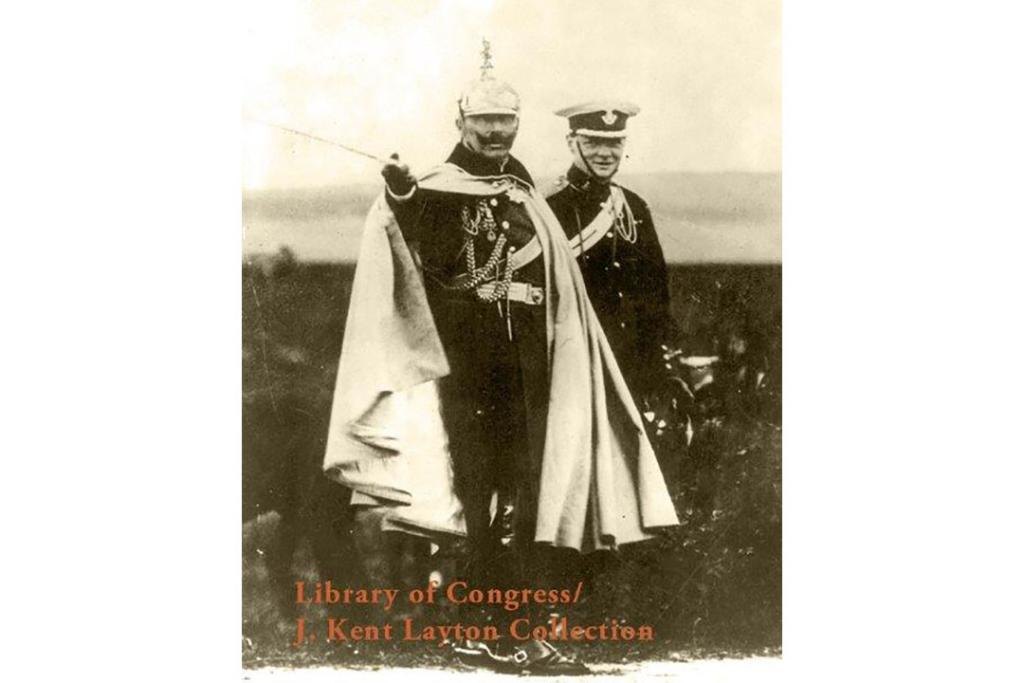

Germany's Kaiser Wilhelm II and England's Winston Churchill

together before the outbreak of war.

© Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division/J Kent Layton Collection

On 28 June 1914 the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, and his wife were assassinated in Sarajevo, Bosnia. Very few people in the world had ever heard of this unfortunate couple, nor could they possibly have imagined what would soon result from the crime. The problem was that all of Europe had for years been divided into two armed camps. Several times incidents had threatened to become all-out European war, but each time the peril had been averted—sometimes by only a narrow margin. This crisis would prove sadly different. Tensions quickly began to escalate. Exactly one month after the assassinations, 28 July, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. The other major powers followed over the next few days, and then on 4 August, Great Britain finally joined what had become a total European war.

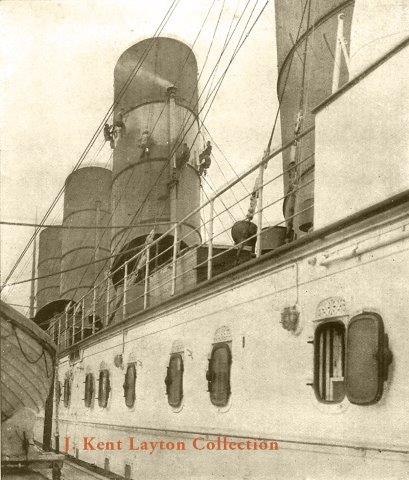

During the first east-bound crossing made by the Lusitania after the outbreak of war,

her upper works were painted in a drab grey to help make sure enemy ships couldn't see her as easily.

© J Kent Layton Collection

The naval theatre of the conflict would be that which most affected the Lusitania and other great liners. At first, there was a great anxiety about the safety of the Lusitania and other ships; since there was no warning about the conflict's outbreak, the war declarations caught many ships literally in mid-ocean. There were fears that German warships or surface raiders—armed merchant cruisers fulfilling a purpose such as that originally envisaged for the Lusitania and Mauretania—could catch them and destroy them. The Mauretania made a mad dash for New York, and arrived safely. The Lusitania was preparing to depart New York. When she did, she carried very few passengers looking for a holiday on a now war-torn continent; she also carried a large consignment of drab grey paint, which her crewmen quickly slapped on her upper works, funnels, hull and superstructure. It was an attempt to make the ship less visible to potential enemies as she travelled to Liverpool; she also arrived safely. The fears were not that long-lived, however.

The German Navy was quickly bottled up in port and their threat of armed merchantmen never fully materialised on the North Atlantic. The greatest danger posed to merchant ships seemed to be that of German mines; in a short time, the Lusitania's attempts at masquerade were ended and she was repainted in her traditional livery. However, things were far from normal: after an initial surge of west-bound bookings from Americans looking to flee Europe, trans-Atlantic travellers quickly seemed to become an endangered species. The numbers of people looking to take passage simply would not hold up the number of ships in service. The Mauretania was laid up, as were many others; the Lusitania was kept in service, with one of her boiler rooms closed down to conserve coal and reduce costs. With these cost-saving measures in place, the Lusitania was once again without peer on the Atlantic. She soldiered on through that winter of 1914-1915 all but alone. But with the coming of spring, change was in the air.