Lusitania: cost overruns and teething troubles

This blog post is the third in a series written by maritime historian and author J Kent Layton, the author of ‘Lusitania: an illustrated biography’, to accompany the exhibition Lusitania: life, loss, legacy

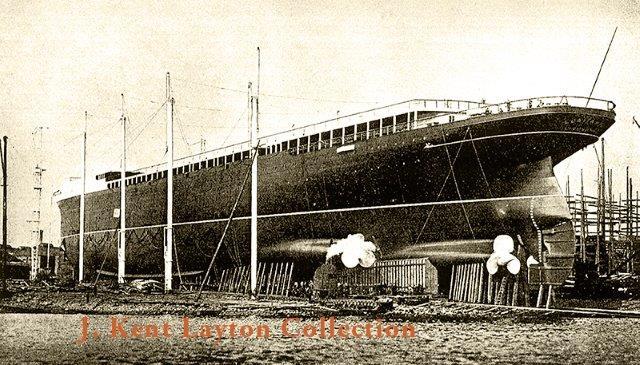

The Lusitania stands on the ways nearly ready for launch. J. Kent Layton Collection

Over the years, I have tried to 'fill in the blanks' in the Lusitania's history. One of the most fascinating things about the construction of the Lusitania and Mauretania is that not everything went according to plan. The £2.6 million loan from the Government was to facilitate the construction of two liners of about £1.3 million each. However, when the two shipyards that would build the liners – John Brown & Co. on the Clyde River for the Lusitania and Swan, Hunter & Wigham Richardson for the Mauretania – were selected, their tenders for construction costs were incomplete, not even including all of the expected costs for construction and for the costly interior décor. Even more astonishing, the contracts for the liners were not signed before construction commenced and when they were, they were not for a fixed price. Instead, both ships were built under the 'cost-plus' arrangement which so many students of Titanic's history are familiar with. In other words, the total paid for each ship would comprise their actual 'cost', 'plus' a percentage of profit for the shipyard. The shipyards were to submit a monthly bill for costs, which Cunard would draw from the loan. Yet the ships were wholly unprecedented; no one had experience building anything that big or expensive.

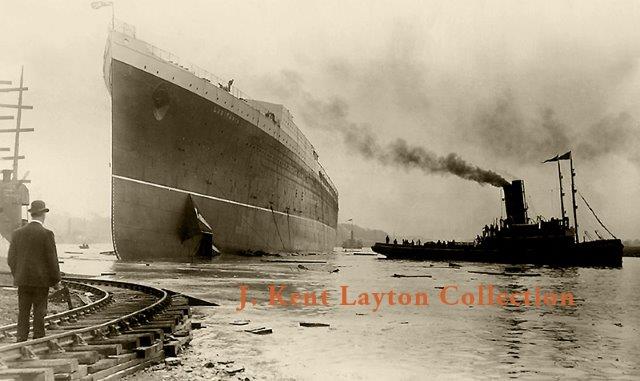

7 June 1906 and the Lusitania rides in the water for the first time

immediately after her launch. J. Kent Layton Collection

It was all a recipe for disaster, and trouble began brewing quickly. Costs on both vessels skyrocketed as construction proceeded, and it became clear that the loan would be exhausted well before the liners were finished. Costs were particularly high with the Mauretania, and relations between Cunard & Swan, Hunter grew so bad that Cunard temporarily suspended monthly payments. Yet, contractually, Cunard was forced to resume the payments, and to assume the added financial burden themselves. To accomplish this, they were forced to raise capital on debentures. Eventually, and after no small amount of negotiation, each shipbuilder agreed to a modest rebate on the total cost of the ship they had built.

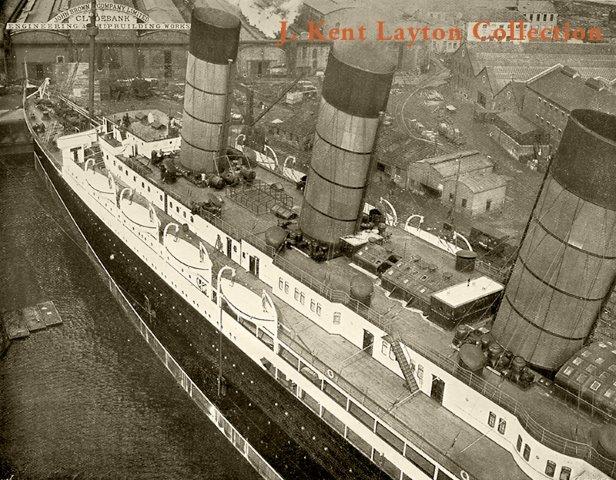

This view was taken from atop the crane used in fitting out the massive liner,

which is clearly nearing completion. (J. Kent Layton Collection)

When the Lusitania entered service, she was the most expensive ship in the world. When all was said and done, Cunard paid some £1,625,463 for her; the Mauretania then became the most expensive, costing Cunard a total of £1,812,252. Total expenditure for the two liners thus amounted to £3,437,715 – or £837,715 more than the Government loan which had funded their construction. In addition to the cost overruns in construction of the two liners, both ships were initially troubled by issues of vibration in their structure, particularly at high speed. The problem was particularly apparent with the Lusitania during her preliminary trials, and meant that some portions of the ships – especially their Second Class regions astern – would be all but uninhabitable, and certainly a far cry from 'comfortable'. John Brown engaged in a series of modifications to stiffen the hull of the Lusitania in order to reduce vibration; the modifications helped tremendously, but throughout her career there would be continued attempts to further improve the situation with her vibration.