Pembroke Place - read all about it!

Today we have a guest blog from Lucy Kilfoyle, a researcher in the History Department at the University of Liverpool. Lucy is leading a team of volunteers investigating historic newspapers as part of the Galkoff's and Secret Life of Pembroke Place project.

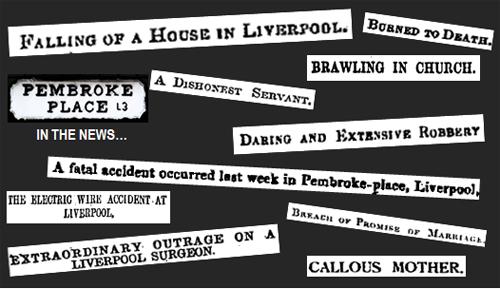

'Tragic accidents, grisly murders, heart-rending tales of good people fallen upon hard times: what’s not to like? At first glance, historical newspapers are not exactly the most glamorous of places to find human interest stories from the past. Invariably, old papers and journals are dull and faded and unrelentingly uniform in appearance. The font is often minute and the text packed densely together. Until well into the late 19th century, pictures and graphics were few and far between. And the language, of course, can be pretty turgid. We’re used, today, to bells and whistles when it comes to journalism – hyper-visual stimulation and punchy, in-your-face copy – and it takes a determined and patient soul (and a hefty dose of stamina) to trawl through columns and columns of stilted Victorian prose! Digitisation is a godsend and using online historical newspaper sources can and does speed up the research process – but these selective archives and their search engines present their own challenges to the unwary.

Given all this, the first thing I warned our ‘newspaper research’ team was that rooting around Liverpool’s historical press in our quest to unearth the history of the Pembroke Place district would be a challenge - but a fascinating and rewarding one, if we did it right. Via articles and editorials, classifieds and adverts, historical newspapers obviously provide factual detail which tells us the ‘who, what, where, when, how and why’ of times gone by. But they’re also a rich source for the fleshing out that detail, helping us to build up impressionistic pictures of the lives led by those fleetingly mentioned by name, age and occupation. What’s more, because newspapers have never been entirely objective purveyors of news (whatever the print media might like to think), they offer an authentic snapshot of contemporary thinking, of social mores and of class prejudices.

Working through Liverpool’s 19th and early 20th century newspapers will hopefully help us to tap into that thinking; to gain a perspective upon how the Pembroke Place area was regarded by the wider Liverpool community. Was it thought of as a ‘posh’ district? A ‘rough’ one? Did it morph from one into the other, over time? It’s very early days yet, in our quest to find information about the 'secret life' of the locale – but we’re already obtaining fascinating insights into the lives and lifestyles of those who lived there. It does take some digging. As it happens, direct 19th century press references to Pembroke Place itself are fairly readily found.

Throughout most of the century (and particularly during the first half), it represented a respectable – even well-to-do – locale, inhabited by the middle and upper classes. These were the types whose professional and civic activities warranted a mention in the public record and who had the time, inclination and cash publicly to share their personal life events (births, deaths and marriages) via the ‘classified’ BMD columns. What’s more, Pembroke Place was the occasional meeting place for learned societies and the location of a number of important medical institutions founded during the period. As a result, it did appear now and then – if mainly incidentally - in the pages of both the local and national papers. The impression that’s already begun to emerge is one of a bustling, cosmopolitan, dynamic thoroughfare, a commercial and residential centre, full of human interest! That’s the comfortable middle classes, though.

A notable feature of historical Liverpool was the way in which the rich lived ‘cheek by jowl’ with the poor. What of the latter; the ‘Great Unwashed’? Those who lived and worked in the courts situated off Pembroke Place – Watkinson('s) Terrace and Watkinson('s) Buildings and, just behind, Missionary Buildings - and the other side-streets and alleyways in the immediate vicinity? Part of our challenge is to try to ferret out newspaper evidence and illustration of these far more elusive, ‘ordinary’ lives, which social history has until fairly recently tended to treat as a lumpen mass.

Researching these is far more difficult. Unsurprisingly, the ‘workaday’ Pembroke Place back-streets, out of sight, out of mind and home to the skilled and unskilled working classes, were of little interest to contemporary chroniclers. It was only when they played host to the occasional, unusual (inevitably tragic or criminal) event, that they became newsworthy and garnered a passing reference in the press.

So far, we’ve unearthed tales of bankruptcy, robbery, accidental infant death and bloody crimes of both passion and greed and we look forward to learning more about the characters involved and to factoring what we learn into the ‘bigger picture’. We do have to remember, of course, that we’re dealing with extreme life events when we stumble upon such ‘newsworthy’ stories, which don’t necessarily reflect the routine experience of most people going about their everyday lives. But they are a reminder that life in pre-20th century Liverpool was precarious – full of insecurity, danger and risk – for all classes (but for the ‘lower orders’, in particular). And such stories are very suggestive of broader societal truths, if we read between the lines and ask searching questions about both the events reported and the way in which they were described by contemporary local journalists.'

Keep a look out – we shall share a tale or two with you soon! Follow this Heritage Lottery Fund supported project on Facebook or join our e-newsletter if you'd like to keep up-to-date with the project."