From Perec Gelkopf to Percy Galkoff

Today we have a guest blog from Lucia Morawska, a volunteer who has been researching the Galkoff family history as part of the Galkoff's and Secret Life of Pembroke Place project.

"P. Galkoff Kosher Butcher Shop has been a recognisable feature of Liverpool for decades. Its beautifully-tiled deep green façade with golden Hebrew engravings now seems out of place in a neighbourhood created by many cultures, languages and religions. In the heart of Liverpool, a place of transition, unwished settlement, new hopes and entrepreneurship, Galkoff’s is a feature many are aware of but few know about. Like many other Liverpool landmarks, Galkoff’s history stretches back further than its time in the city. Percy Galkoff, the founder of the shop, was not always known as Percy. Upon his arrival in Liverpool in 1905, his last name was noted as Galkoff, and he was said to hail from Schertz in Russia (now Poland). In fact, Percy was born in 1877 as Perec (or Perez) Gelkopf in the small village of Jakubice between Warta and Sieradz in central Poland. He was one of the thousands of Eastern European Jews arriving in Britain during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Jewish records indexing the distribution of the surname 'Gelkopf' in Poland

At the time, the small village of Jakubice lay in the heart of the so called Polish Kingdom (or Congress Poland) and was ruled by the Russian Empire after the Napoleonic wars. Prior to that, the region was under rule of the Prussian Empire as a result the Third Partition of Poland in 1795. According to the Polish Registry Office records Zelma(n) Gelkopf was, at the time of Percy’s birth, an inn keeper, most likely on the outskirts of Jakubice, close to the road linking Warta and Sieradz. Jews in Poland began to lease taverns, inns and village breweries in the late medieval period. By the 19th century inn keepers made up as much as 55% of the total Jewish population in and around central Poland.

Interestingly, Percy’s grandfather, Perec Gelkopf (born 1813), is listed as (Polish) ‘pachciarz’, or ‘pakciarz’ from the Latin word ‘pactum’. This refers to a person holding a ‘pact’, or agreement on lease of a property, often an inn or a mill. The births of both Percy and his father, Zelma (1854), were entered into Warta’s Book of Births, Marriages and Deaths. Yet records show that the family later moved to Szczercow, where some of Percy’s many siblings were born. Zelma and Percy’s mother Fajga (nee Konopnicka), are registered as homeowners in the municipal registry records of the 1890s.

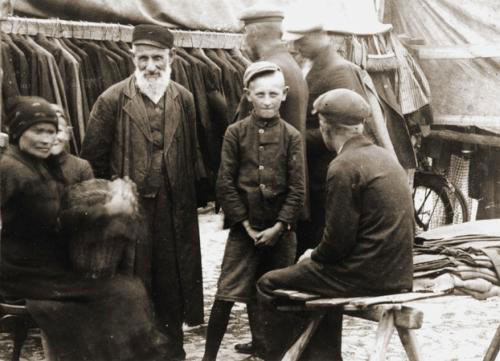

Jewish people in Szczercow. Courtesy of JewishGen http://www.jewishgen.org

The history of the Jewish settlement in Szczercow probably dates back to the 18th century. Due to anti-Jewish pogroms in Russia, many Jewish people embarked on the journey to Poland and often settled in small provincial towns. In 1841 there were around 300 Jewish people among the 1500 residents of Szczercow. Before the First World War Szczercow had a synagogue, a Jewish school and a Jewish bank. Traditionally, Polish Jews were involved in trade and various crafts. Occasionally, especially in rural areas, Jewish people owned or, more often, leased land. Many worked as peddlers touring the Polish countryside selling and buying various goods, from needles to agricultural machines. The majority of Jewish people in Poland remained poor or extremely poor, with large families often living off charitable donations from their local Jewish councils. Yet within these poor areas, there existed great examples of brilliant entrepreneurship, especially in the rapidly industrialising central Poland.

In the 19th century nearby Lodz, only 30 miles away from Szczercow, started to grow into a textile empire. The city began to form a new identity as a promised land of many cultures, nationalities and religions. Among its residents were great Jewish entrepreneurs, such as textile princes like Marcus Silberstein or Israel Poznanski, whose factories employed thousands of workers. This economic climate of rapid prosperity and industrial development induced further Jewish migration both from the west and the east.

The Jewish populations continued to swell in both large urban centres and smaller towns like Szczercow and Warta. In 1897 over 50% of the overall population of Warta was Jewish. It is safe to assume that the Gelkopf family was better off than the average Jewish resident of Szczercow in the late 19th century. As a property owner Zelma Gelkopf probably made some profit from letting and leasing. Many small town residents ran their enterprises from home. However, the Gelkopfs were far from local property magnates. In 1860 Szczercow had just four brick houses, its streets were unpaved and most of its inhabitants worked on the land to subsidise their living. In fact, Szczercow resembled a village rather than a several centuries old town. Many urban properties suffered from terrible overcrowding similar to that of inner Liverpool. In 1900 as many as 4700 residents lived in just 365 properties - an average of over 12 inhabitants per house!

Typically, provincial one-storey houses were tightly built around a main town square, with backyards shared between humans and animals. A street pump that served multiple families was the only source of fresh water; there was not even a sewage system until some point in the 20th century. Due to overcrowding within the wooden buildings, fires were common and usually devastating. For example, in 1880 a single fire consumed as much as a third of properties in Szczercow.

Percy Galkoff (front left) in a family photograph in the 1940s. Courtesy of Toubkin/Galkoff family

Life in a Jewish town within Eastern Europe was not as idyllic as it is portrayed by Mark Chagall in his paintings of the Belarusian town of Vitebsk. The shtetl was indeed inhabited by the poor but pious men humming klezmer songs and practising bottle dancing. Yet it was also a little town without proper roads, occasionally sinking under the seasonal floods, devastated by the repressive policies and discriminatory laws of the Russian government.

Many Jewish men feared the infamous Russian military service, known for its length (up to 25 years) and brutality. From 1827 the Russian army could not only demand the services of adult recruits, but also boys under the age of 12. This system attempted to drag children out of their communities before they had become influenced by the Jewish culture and tradition. Conscription rules thus became a real threat to the traditional status of Jewish society. By partitioning Poland, the Russian Empire not only gained a large territory in the West but inherited a Jewish population of some 900,000 (around seven percent of the population).

From the 19th century onwards, different Russian rulers looked either to expel or bar the Jewish from Russia. Yet after Russia took control of a large section of Poland, the approach proved impractical within the new territory. Polish Jews were mostly concentrated in towns and their re-settlement to any other distant territory could potentially result in an economic chaos. The army with its long service (Tsar Alexander II reduced it from 25 to 5 to 10 years ‘only’) seemed the perfect solution. Imperial legislation aimed to solve the Jewish problem through coerced and intensified assimilation or Russification but also, by alienating young Jewish men from their families, communities, native Yiddish and religion. Jewish soldiers in the Russian army were often forbidden to practice their rituals and bullied into attending Christian classes and services.

Percy (Perec) Galkoff did not manage to avoid military conscription and served as a drummer during the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-1905. Although not much is known about his life in the barracks, it is safe to say it must have been pretty challenging. In January 1903 The Spectator noted, "Even now the lot of the Hebrew in the Russian Army is exceptionally hard. His life is made bitter to him by every species of insult, often by ill-treatment of the grossest kind". It is no wonder that upon his naturalisation, Percy refused military service in the British Army by excusing himself as a family man and a sole bread winner. In this climate, many Jewish people made desperate moves to escape persecution and forceful conscription.

It is estimated that between 1875 and 1914 over 120,000 Eastern European Jews settled in Britain, amongst them Perec Gelkopf, whose new life started with a misspelled surname."