Polari and the Hidden History of Gay Seafarers

“Oh hello Mr Horne! How Bona to vada your dolly old eke!”

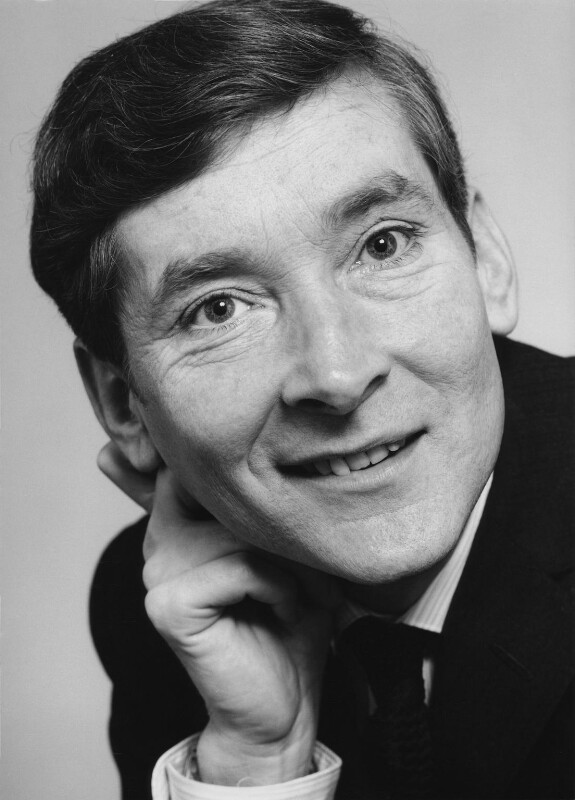

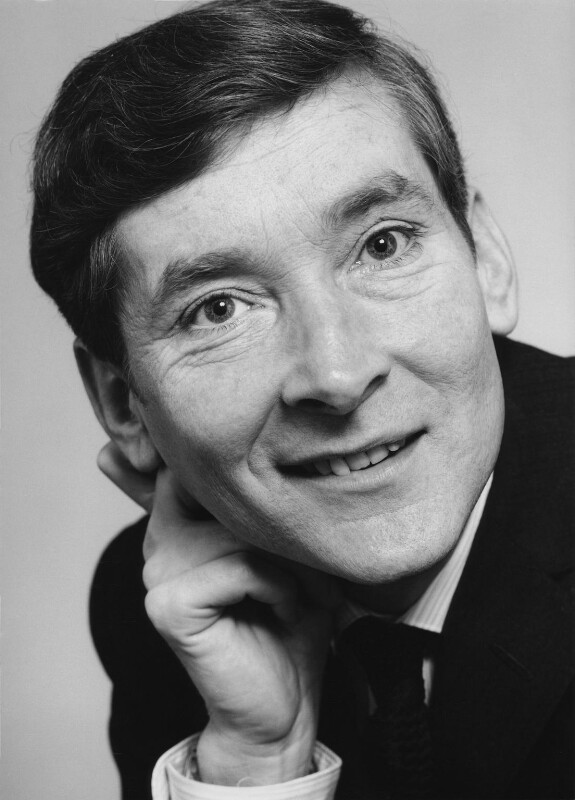

The above quote was taken from an extremely popular radio comedy programme in the 1960s called Round the Horne, which featured a pair of camp characters called Julian and Sandy (played by Hugh Paddick and Kenneth Williams). They used a secret gay form of language called Polari. “Bona to vada your dolly old eke” meant “nice to see your pretty old face”. Gay people used this language up until around the 1970s as a way of conducting conversations in public spaces or just to have a camp laugh with each other. For some, it was just a collection of a few slang words. But others used it in a more complex way, making it sound like a proper language.

Polari is a bit of a magpie – borrowing terms from Italian, Cockney Rhyming Slang and Yiddish, as well as incorporating slang words from the gay subculture of the time. Some words were spoken as if they were spelled backwards, like ecafe (face), although to make it more complicated, ecafe was shortened to eke or eek. There are no standardised spellings incidentally, and many of the older speakers knew Polari as Palare, Parlary or Palari. Some of them get quite cross with the “Polari” spelling, which was used by the lexicographer Eric Partridge back in the 1950s and seems to have stuck.

Polari was popular in theatres around the UK and many actors still know a few words. An older form of it called Parlyaree was used in the 19th century by travelling entertainers and fairground people, and from there it found its way into the music halls and then the theatres. Backstage, dancers were called wallopers and singers were voches. Another popular place to have heard it would be in the cabins of the crew of glamorous cruise liners (latties on water). In the ‘50s and ‘60s more than a few gay men joined the Merchant Navy to serve as waiters or stewards and there was a strong sense of community among them. The Merch’ was a place of freedom for these men, who were able to escape the oppressive atmosphere back home. They camped it up, put on drag shows and generally had a whale of a time, often making lifelong friends and forming relationships. They called themselves queens or girls and “christened” one another with Camp Names like The Black Widow, Scotch Flo or Lana Turner. Sometimes these names could contain a little sting in them, to stop someone from getting too uppity. And it was not unknown for these men to get into relationships with the butch straight men onboard.

Once women and people from countries like Goa and Mexico started to get employed in the ‘70s and ‘80s, the gay subculture onboard declined quite a bit and Polari itself was starting to be seen as superfluous. The Round the Horne sketches in the late 1960s had introduced Polari to the mainstream public and homosexuality was partially decriminalised in 1967 so speaking in a secret code was starting to be seen as a bit naff (itself a Polari word). Times were changing and many younger gay people wanted to be out and were concerned with political rights. Polari was starting to be seen as an old man’s thing and not very politically correct.

But by the 1990s views started to change again. A group of male nuns called the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence adopted Polari in their ceremonies. The Sisters are a political organisation providing help to gay communities in various ways. They canonised the gay film director Derek Jarman, months before he died from an AIDS related illness. Jarman said it was one of the happiest moments of his life. And gradually, interest in this secret and almost forgotten language grew, with academics like me getting in on the act – I made Polari the subject of my PhD in the late 1990s, interviewing some of the original speakers and charting its history. It was a result of that research that I wrote Hello Sailor with Jo Stanley which focussed on the untold story of gay seafarers in the Merchant Navy, which also led to the exhibition at Merseyside Maritime Museum.

These days, thanks to the internet, there’s a lot more information about Polari out there, and it’s being discovered by newer generations. It’s even gotten a little bit cool again, with artists using it in a range of artwork. It is sometimes used as a kind of brand name to label gay bars and cafes, and there’s a clothing range named after it. It even has an Iphone app!

However, it’s not welcome everywhere. In February 2017 an Evensong in Polari was performed at Westcott House in Cambridge as a way of sending an inclusive message to LGBT people. Part of the translated version reads “Fabeness be to the Auntie and to the Homie Chavvie, and to the Fantabulosa Fairy”. Some members of the audience were upset by this and complained, resulting in a bit of a media storm and apologies having to be made. There were divided opinions about whether Polari had a place in a religious ceremony and whether the reaction was over the top. Whatever you think about it, Polari still has the capacity to shock and surprise – and that’s what it’s always done. Eric Partridge called Polari a Cinderella among languages. But I like to think of it as the Ugly Sisters – brash, funny and with all the best lines in the show.

My book, Fabulosa: The Story of Polari, Britain’s Secret Gay Language came out in 2019. You can also have a vada at the companion website.