Guillemont Road Cemetery, where many King’s Regiment soldiers are buried

As night fell on 8 August 1916, a few of the men from the 1st Battalion had escaped the attack and found their way back to the British Front Line. Of the hundreds of men in the battalion, who had gone over the top that morning, only 180 were available to answer their names at roll call.

The battle for the village of Guillemont described in yesterday’s blog continued however, as the remaining men of the 8th (Irish) Battalion were still trapped in the village.

Zero hour on 9 August was once again 4.20am with the same objective lines. This time the 6th and 7th battalions were to head the attack and were joined by the 10th (Liverpool Scottish) Battalion.

During this attack, the 10th Battalion’s Medical Officer, Noel Chavasse was awarded the Victoria Cross for his bravery. Noel was the son of the Bishop of Liverpool and was the only man ever to have been awarded two Victoria Crosses during one war. Sadly, the second one, in 1917, was awarded posthumously.

Just making their way to their zero hour rendezvous point had been almost impossible. The trenches that were still intact were crowded with wounded men making their way back from the battle and dead bodies. The British Front Line was also so badly damaged by enemy shells, that other troops failed to reach their rendezvous point because the trench they were looking for no longer existed. There was confusion along the whole line – men were delayed, orders could not be circulated and locations were uncertain. At least one battalion commander requested that zero hour be delayed, but the request was refused. The attack would go ahead as planned.

It is probably not surprising that in such confusion, few details of the attack were recorded. The records do show that the 6th and 7th Battalions managed to progress only a very short distance before being pinned down.

The 10th (Scottish) Battalion had only just made it to their ‘jump off point’ by zero hour. The Loyal North Lancashire’s, meant to support their left flank, had not made it in time and the 10th Battalion were forced to advance without them. They made it to the German wire, but were forced to retreat under a hail of gunfire. They pushed forward again and again, but each time they were beaten back. By nightfall, the 10th had not advanced their position at all. The attack on 9 August had failed again and 36 hours after they had left the British Front Line, the last of the 8th (Irish) men trapped in the village, were either captured or killed.

The fighting continued and on 12 August, the 9th Battalion, the last of the Terrier Battalions moved up to the Front Line, ready to advance. This time Zero hour would be 5.15pm. The attack was preceded by a short bombardment of just two hours. The 9th moved forward under heavy fire, but quickly reached their objective. The story was all too familiar – the men were outflanked and were forced to retreat. By midnight, apart from a slight gain of land by one Company, almost all of the attacking troops were back where they had started.

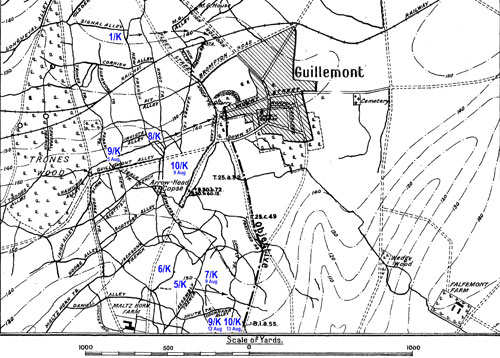

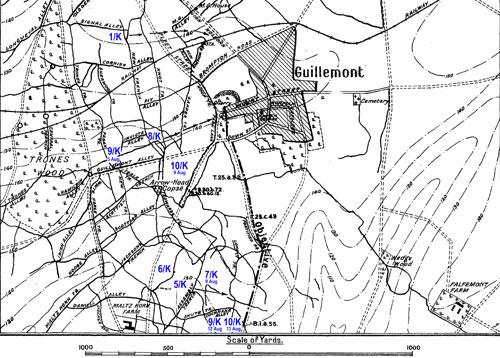

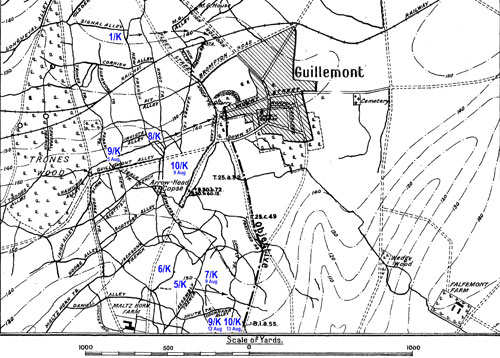

This map shows the position of the Territorials and 1st Battalion (marked in blue), in the third attack on the village. The arrows show their proposed movement to their objective lines.

The 55th Division moved out of the Front Line on the night of 14 August. They had been in action for two weeks. In that time the British line had moved forward an average of just 360 metres. The Liverpool Territorial and 1st Battalion losses (including wounded and prisoners) had run into thousands, with 680 men confirmed killed.

Still the fight for Guillemont continued – look out for our next

Somme blog in September to find out how yet more Merseyside men were involved.

Each day of the Somme commemorations, we are

tweeting about the men featured on our King’s Regiment database. We are currently unable to carry out individual family history research, however, you can

view the online index of the 91,000 men listed on the database or visit our

City Soldiers gallery in the Museum of Liverpool to view the full database.

Guillemont Road Cemetery, where many King’s Regiment soldiers are buried

As night fell on 8 August 1916, a few of the men from the 1st Battalion had escaped the attack and found their way back to the British Front Line. Of the hundreds of men in the battalion, who had gone over the top that morning, only 180 were available to answer their names at roll call. The battle for the village of Guillemont described in yesterday’s blog continued however, as the remaining men of the 8th (Irish) Battalion were still trapped in the village.

Zero hour on 9 August was once again 4.20am with the same objective lines. This time the 6th and 7th battalions were to head the attack and were joined by the 10th (Liverpool Scottish) Battalion.

Guillemont Road Cemetery, where many King’s Regiment soldiers are buried

As night fell on 8 August 1916, a few of the men from the 1st Battalion had escaped the attack and found their way back to the British Front Line. Of the hundreds of men in the battalion, who had gone over the top that morning, only 180 were available to answer their names at roll call. The battle for the village of Guillemont described in yesterday’s blog continued however, as the remaining men of the 8th (Irish) Battalion were still trapped in the village.

Zero hour on 9 August was once again 4.20am with the same objective lines. This time the 6th and 7th battalions were to head the attack and were joined by the 10th (Liverpool Scottish) Battalion.

During this attack, the 10th Battalion’s Medical Officer, Noel Chavasse was awarded the Victoria Cross for his bravery. Noel was the son of the Bishop of Liverpool and was the only man ever to have been awarded two Victoria Crosses during one war. Sadly, the second one, in 1917, was awarded posthumously.

Just making their way to their zero hour rendezvous point had been almost impossible. The trenches that were still intact were crowded with wounded men making their way back from the battle and dead bodies. The British Front Line was also so badly damaged by enemy shells, that other troops failed to reach their rendezvous point because the trench they were looking for no longer existed. There was confusion along the whole line – men were delayed, orders could not be circulated and locations were uncertain. At least one battalion commander requested that zero hour be delayed, but the request was refused. The attack would go ahead as planned.

It is probably not surprising that in such confusion, few details of the attack were recorded. The records do show that the 6th and 7th Battalions managed to progress only a very short distance before being pinned down.

The 10th (Scottish) Battalion had only just made it to their ‘jump off point’ by zero hour. The Loyal North Lancashire’s, meant to support their left flank, had not made it in time and the 10th Battalion were forced to advance without them. They made it to the German wire, but were forced to retreat under a hail of gunfire. They pushed forward again and again, but each time they were beaten back. By nightfall, the 10th had not advanced their position at all. The attack on 9 August had failed again and 36 hours after they had left the British Front Line, the last of the 8th (Irish) men trapped in the village, were either captured or killed.

The fighting continued and on 12 August, the 9th Battalion, the last of the Terrier Battalions moved up to the Front Line, ready to advance. This time Zero hour would be 5.15pm. The attack was preceded by a short bombardment of just two hours. The 9th moved forward under heavy fire, but quickly reached their objective. The story was all too familiar – the men were outflanked and were forced to retreat. By midnight, apart from a slight gain of land by one Company, almost all of the attacking troops were back where they had started.

During this attack, the 10th Battalion’s Medical Officer, Noel Chavasse was awarded the Victoria Cross for his bravery. Noel was the son of the Bishop of Liverpool and was the only man ever to have been awarded two Victoria Crosses during one war. Sadly, the second one, in 1917, was awarded posthumously.

Just making their way to their zero hour rendezvous point had been almost impossible. The trenches that were still intact were crowded with wounded men making their way back from the battle and dead bodies. The British Front Line was also so badly damaged by enemy shells, that other troops failed to reach their rendezvous point because the trench they were looking for no longer existed. There was confusion along the whole line – men were delayed, orders could not be circulated and locations were uncertain. At least one battalion commander requested that zero hour be delayed, but the request was refused. The attack would go ahead as planned.

It is probably not surprising that in such confusion, few details of the attack were recorded. The records do show that the 6th and 7th Battalions managed to progress only a very short distance before being pinned down.

The 10th (Scottish) Battalion had only just made it to their ‘jump off point’ by zero hour. The Loyal North Lancashire’s, meant to support their left flank, had not made it in time and the 10th Battalion were forced to advance without them. They made it to the German wire, but were forced to retreat under a hail of gunfire. They pushed forward again and again, but each time they were beaten back. By nightfall, the 10th had not advanced their position at all. The attack on 9 August had failed again and 36 hours after they had left the British Front Line, the last of the 8th (Irish) men trapped in the village, were either captured or killed.

The fighting continued and on 12 August, the 9th Battalion, the last of the Terrier Battalions moved up to the Front Line, ready to advance. This time Zero hour would be 5.15pm. The attack was preceded by a short bombardment of just two hours. The 9th moved forward under heavy fire, but quickly reached their objective. The story was all too familiar – the men were outflanked and were forced to retreat. By midnight, apart from a slight gain of land by one Company, almost all of the attacking troops were back where they had started.

This map shows the position of the Territorials and 1st Battalion (marked in blue), in the third attack on the village. The arrows show their proposed movement to their objective lines.

The 55th Division moved out of the Front Line on the night of 14 August. They had been in action for two weeks. In that time the British line had moved forward an average of just 360 metres. The Liverpool Territorial and 1st Battalion losses (including wounded and prisoners) had run into thousands, with 680 men confirmed killed.

Still the fight for Guillemont continued – look out for our next Somme blog in September to find out how yet more Merseyside men were involved.

Each day of the Somme commemorations, we are tweeting about the men featured on our King’s Regiment database. We are currently unable to carry out individual family history research, however, you can view the online index of the 91,000 men listed on the database or visit our City Soldiers gallery in the Museum of Liverpool to view the full database.

This map shows the position of the Territorials and 1st Battalion (marked in blue), in the third attack on the village. The arrows show their proposed movement to their objective lines.

The 55th Division moved out of the Front Line on the night of 14 August. They had been in action for two weeks. In that time the British line had moved forward an average of just 360 metres. The Liverpool Territorial and 1st Battalion losses (including wounded and prisoners) had run into thousands, with 680 men confirmed killed.

Still the fight for Guillemont continued – look out for our next Somme blog in September to find out how yet more Merseyside men were involved.

Each day of the Somme commemorations, we are tweeting about the men featured on our King’s Regiment database. We are currently unable to carry out individual family history research, however, you can view the online index of the 91,000 men listed on the database or visit our City Soldiers gallery in the Museum of Liverpool to view the full database.