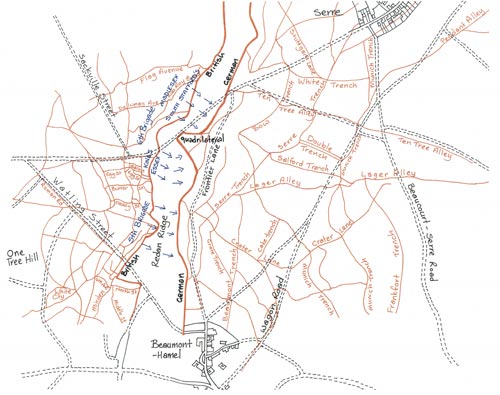

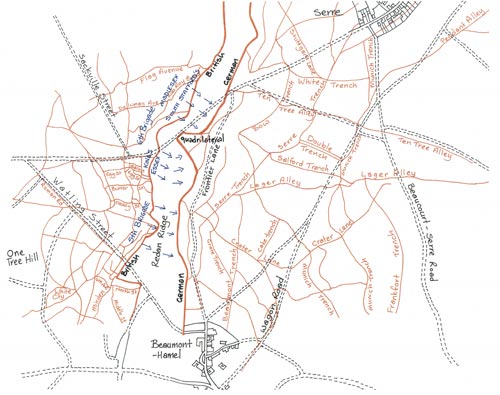

Map of the Battle of Ancre. The red lines indicate the trenches, with the thicker lines showing the British and German front lines on 13 November.

Since 1 July, I have been

blogging about some of the significant attacks in the Battle of the Somme involving the

King’s Liverpool Regiment. This is the final one of the series.

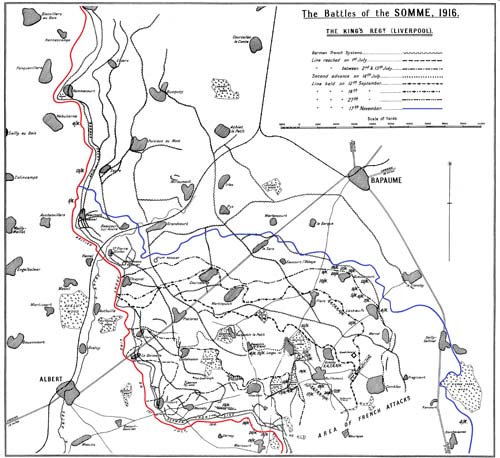

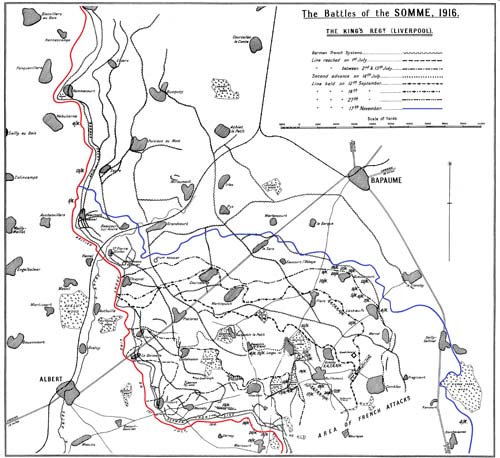

Map of the Somme region. The red line indicates the position of the British Front-line on 1 July 1916. The blue line indicates the position of the line when the Somme battle ended on 18 November. The upper part of the Line had not moved.

This Imperial War Museum image, taken in November 1916, shows British troops struggling to move captured artillery through the mud.

The Battle of the Ancre was the final large British push on the Somme in 1916. The British front line, north of Thiepval had barely moved since July. Pushing the line forward would remove a vulnerable salient, and move the British Forces on to higher ground, giving them a tactical advantage.

Originally planned for September, the attack was cancelled several times, as the region experienced some of the worst weather in decades. The mix of torrential rain and artillery bombardment, turned the already marshy valley around the River Ancre into a quagmire of mud, wire and bodies. Into this hell marched the 1st Battalion of the King’s – decimated in earlier

Somme battles, the Battalion had been reinforced with drafts from home totalling 750 men, and was essentially a new, inexperienced unit.

On 13 November, the Battalion was sheltering on open ground in the British front lines, their own trenches so full of mud they were unusable. Part of the 6th Brigade, they were the second wave of the attack, behind the 13th Essex Regiment and would cross no-man’s-land, in the area around Redan Ridge. Their objective was to breech a stronghold of German trenches, known as the quadrilateral, and push through to their second and third lines, at Frankfort trench and Beaucourt-Serre Road.

At 5.45am, they moved forward, into fog so thick that in places the visibility was only 20 yards. The quadrilateral split their Brigade and the King’s followed the Essex to the right while the South Stafford Regiment were forced to the left.

Ahead of them, some of the Essex made it through to German lines, but most were bogged down in no-man’s-land. The King’s moved forward to reinforce them. Some of the King’s and Essex men became trapped behind a ridge, about 30 yards in front of the enemy trenches. Worse still, these men were ordered to hold their positions, effectively, to draw the brutal German machine gun fire away from a more successful push by the 5th Brigade, happening on their right flank.

To their left, the Stafford’s attack had failed. To their right, the 5th Brigade had pushed through into the German lines. The Essex/King’s group had breeched the German lines on their right flank, but had been unable to push far into the quadrilateral on their left. This turned their line of attack in a more northerly direction and they dug a new front line diagonally across no-man’s-land.

The King’s and Essex men continued to push forward under heavy shelling and machine gun fire, even though they had limited bomb supplies and rifles that had clogged in the waist-deep mud. They were finally withdrawn from the trenches on 16 November. During the attack, they had suffered 255 killed, wounded and missing.

The British front line had moved forward during the Battle of the Ancre, and some high ground was gained, but in the northern sector of the Battle, little had changed and north from Serre, the British line was pretty much the same as it had been on 1 July.

Private Charles Sumner was killed during the battle. The 25 year-old had arrived at The Front just five months earlier

The Battle of the Somme officially ended on 18 November. The fight for an area of ground approximately the same size as the Wirral, had raged for 141 days with casualties on both sides totalling more than one million men. The King’s Regiment alone had almost 3,000 killed in the region.

Map of the Battle of Ancre. The red lines indicate the trenches, with the thicker lines showing the British and German front lines on 13 November.

Since 1 July, I have been blogging about some of the significant attacks in the Battle of the Somme involving the King’s Liverpool Regiment. This is the final one of the series.

Map of the Battle of Ancre. The red lines indicate the trenches, with the thicker lines showing the British and German front lines on 13 November.

Since 1 July, I have been blogging about some of the significant attacks in the Battle of the Somme involving the King’s Liverpool Regiment. This is the final one of the series.

Map of the Somme region. The red line indicates the position of the British Front-line on 1 July 1916. The blue line indicates the position of the line when the Somme battle ended on 18 November. The upper part of the Line had not moved.

Map of the Somme region. The red line indicates the position of the British Front-line on 1 July 1916. The blue line indicates the position of the line when the Somme battle ended on 18 November. The upper part of the Line had not moved.

This Imperial War Museum image, taken in November 1916, shows British troops struggling to move captured artillery through the mud.

The Battle of the Ancre was the final large British push on the Somme in 1916. The British front line, north of Thiepval had barely moved since July. Pushing the line forward would remove a vulnerable salient, and move the British Forces on to higher ground, giving them a tactical advantage.

Originally planned for September, the attack was cancelled several times, as the region experienced some of the worst weather in decades. The mix of torrential rain and artillery bombardment, turned the already marshy valley around the River Ancre into a quagmire of mud, wire and bodies. Into this hell marched the 1st Battalion of the King’s – decimated in earlier Somme battles, the Battalion had been reinforced with drafts from home totalling 750 men, and was essentially a new, inexperienced unit.

On 13 November, the Battalion was sheltering on open ground in the British front lines, their own trenches so full of mud they were unusable. Part of the 6th Brigade, they were the second wave of the attack, behind the 13th Essex Regiment and would cross no-man’s-land, in the area around Redan Ridge. Their objective was to breech a stronghold of German trenches, known as the quadrilateral, and push through to their second and third lines, at Frankfort trench and Beaucourt-Serre Road.

At 5.45am, they moved forward, into fog so thick that in places the visibility was only 20 yards. The quadrilateral split their Brigade and the King’s followed the Essex to the right while the South Stafford Regiment were forced to the left.

Ahead of them, some of the Essex made it through to German lines, but most were bogged down in no-man’s-land. The King’s moved forward to reinforce them. Some of the King’s and Essex men became trapped behind a ridge, about 30 yards in front of the enemy trenches. Worse still, these men were ordered to hold their positions, effectively, to draw the brutal German machine gun fire away from a more successful push by the 5th Brigade, happening on their right flank.

To their left, the Stafford’s attack had failed. To their right, the 5th Brigade had pushed through into the German lines. The Essex/King’s group had breeched the German lines on their right flank, but had been unable to push far into the quadrilateral on their left. This turned their line of attack in a more northerly direction and they dug a new front line diagonally across no-man’s-land.

The King’s and Essex men continued to push forward under heavy shelling and machine gun fire, even though they had limited bomb supplies and rifles that had clogged in the waist-deep mud. They were finally withdrawn from the trenches on 16 November. During the attack, they had suffered 255 killed, wounded and missing.

The British front line had moved forward during the Battle of the Ancre, and some high ground was gained, but in the northern sector of the Battle, little had changed and north from Serre, the British line was pretty much the same as it had been on 1 July.

This Imperial War Museum image, taken in November 1916, shows British troops struggling to move captured artillery through the mud.

The Battle of the Ancre was the final large British push on the Somme in 1916. The British front line, north of Thiepval had barely moved since July. Pushing the line forward would remove a vulnerable salient, and move the British Forces on to higher ground, giving them a tactical advantage.

Originally planned for September, the attack was cancelled several times, as the region experienced some of the worst weather in decades. The mix of torrential rain and artillery bombardment, turned the already marshy valley around the River Ancre into a quagmire of mud, wire and bodies. Into this hell marched the 1st Battalion of the King’s – decimated in earlier Somme battles, the Battalion had been reinforced with drafts from home totalling 750 men, and was essentially a new, inexperienced unit.

On 13 November, the Battalion was sheltering on open ground in the British front lines, their own trenches so full of mud they were unusable. Part of the 6th Brigade, they were the second wave of the attack, behind the 13th Essex Regiment and would cross no-man’s-land, in the area around Redan Ridge. Their objective was to breech a stronghold of German trenches, known as the quadrilateral, and push through to their second and third lines, at Frankfort trench and Beaucourt-Serre Road.

At 5.45am, they moved forward, into fog so thick that in places the visibility was only 20 yards. The quadrilateral split their Brigade and the King’s followed the Essex to the right while the South Stafford Regiment were forced to the left.

Ahead of them, some of the Essex made it through to German lines, but most were bogged down in no-man’s-land. The King’s moved forward to reinforce them. Some of the King’s and Essex men became trapped behind a ridge, about 30 yards in front of the enemy trenches. Worse still, these men were ordered to hold their positions, effectively, to draw the brutal German machine gun fire away from a more successful push by the 5th Brigade, happening on their right flank.

To their left, the Stafford’s attack had failed. To their right, the 5th Brigade had pushed through into the German lines. The Essex/King’s group had breeched the German lines on their right flank, but had been unable to push far into the quadrilateral on their left. This turned their line of attack in a more northerly direction and they dug a new front line diagonally across no-man’s-land.

The King’s and Essex men continued to push forward under heavy shelling and machine gun fire, even though they had limited bomb supplies and rifles that had clogged in the waist-deep mud. They were finally withdrawn from the trenches on 16 November. During the attack, they had suffered 255 killed, wounded and missing.

The British front line had moved forward during the Battle of the Ancre, and some high ground was gained, but in the northern sector of the Battle, little had changed and north from Serre, the British line was pretty much the same as it had been on 1 July.

Private Charles Sumner was killed during the battle. The 25 year-old had arrived at The Front just five months earlier

The Battle of the Somme officially ended on 18 November. The fight for an area of ground approximately the same size as the Wirral, had raged for 141 days with casualties on both sides totalling more than one million men. The King’s Regiment alone had almost 3,000 killed in the region.

Private Charles Sumner was killed during the battle. The 25 year-old had arrived at The Front just five months earlier

The Battle of the Somme officially ended on 18 November. The fight for an area of ground approximately the same size as the Wirral, had raged for 141 days with casualties on both sides totalling more than one million men. The King’s Regiment alone had almost 3,000 killed in the region.