Sugar, tea and pottery

Deep in the ground in Liverpool are tangible links to the transatlantic trade in enslaved African people. Pottery occasionally recovered by archaeologists tells the stories of Liverpool’s role in slavery and the ways in which plantations used goods produced in Liverpool and the region, and produced goods imported into the port of Liverpool. Pottery, a mainstay of archaeology, can tell these stories in fascinating ways if you know how to look at it.

Teapot from Paul Scott's 'Cumbrian Blue(s), The Cockle Pickers' Tea Service'

Sometimes it’s seeing modern objects which sparks a link between historic pottery and the stories of the transatlantic slave trade. In 2016 the International Slavery Museum acquired the 'Cumbrian Blue(s), The Cockle Pickers’ Tea Service' by artist, Paul Scott.

This tea service was made to commemorate the Chinese cockle pickers killed in Morecombe Bay in 2004 and modern slavery. It also links to Britain’s involvement in the transatlantic slave trade, reflecting the types of pottery used in Georgian Liverpool for coffee and tea drinking, beverages flavoured with sugar. Sugar produced by enslaved African people. It is striking how alike the tea service is to lot of the 200 year old Staffordshire cups and saucers that were excavated from the Manchester Dock, on the site of the Museum of Liverpool before it was built.

Scott’s 'Cumbrian Blue(s), The Cockle Pickers' Tea Service'

The most intriguing thing about these parallels between the modern and historic objects is the link they make between modern slavery, the transatlantic slave trade and to sugar refining. 200 years ago Liverpool was at the heart of this trade, almost every industry in the town relied on it, and it is still present in the cityscape with many of Liverpool’s historic buildings built as a result of the profits of slavery.

Liverpool was the largest of Britain’s ports engaged in the ‘African trade’ as it was called, the purchase and transportation of enslaved Africans to plantations of North America and the Caribbean. Identifying physical evidence in Liverpool’s archaeological record is key to understanding the transatlantic trade in enslaved Africans and how it seeped into all areas of Liverpool life.

Glass beads

Alongside the many Staffordshire cups recovered from the excavations, which were probably intended for export to the United States, were two beads. They are on display in the Manchester Dock Spotlight display in our History Detectives gallery at the Museum of Liverpool, where they can be easily overlooked within such a large case. But these two small objects are pretty much the only excavated evidence from Liverpool of the millions of items bought by the town’s merchants to transport to Africa to trade for people.

A small group of Liverpool slave traders, including William Davenport, formed a company under his name: William Davenport & Co. This company became the supplier of half of all the glass beads, mainly made in Venice and around Prague, that were re-exported to Africa to buy enslaved Africans. In just four years, between 1766 to 1770, the company sold £39,000 worth of beads, equating to almost £7,000,000 in today’s money.

That is a lot of beads and we have found very few in Liverpool as almost all of them were exported. Enslaved African people were taken to the Caribbean where they worked on plantations growing cane sugar which, after initial processing, came back to Liverpool to be refined into expensive white sugar which was in high demand in Europe.

Staffordshire pottery

It was the imports of sugar, tea and coffee which drove the growth of a culture of coffee houses (which also sold tea), and created the demand for fine cups from the 17th century, and later the fancy tea services which we know today. Liverpool was the major port used to transport Staffordshire pottery to the United States and around the world.

The 200 year old cups and saucers excavated on the site of the museum are evidence of this, probably intended for export and to be used to serve drinks, with ingredients produced by enslaved labour.

Sugar refining pottery

Further evidence of the role Liverpool played in slavery comes from another group of pottery also excavated on the site of the Museum of Liverpool: a huge collection of sugar refining pottery.

Just some of the huge quantities of sugar refining pottery recovered in 2007, in a former display at the Museum of Liverpool

Most of it is badly broken, but this is a really significant archaeological find, it is all that is left from the many small sugar refineries which existed right in the centre of Liverpool 200 years ago. Long before the large factories like Tate and Lyle developed there was a sugar-refining industry in Liverpool. The pottery was made at William Ashcroft’s Moss Pottery in Prescot for the Liverpool sugar refiners.

The raw sugar was produced by enslaved Africans on the plantations of the Caribbean and sent back to Liverpool to be refined into the high quality expensive sugar sold in Europe. This process used these pots, some of which are badly worn showing that they were heavily used. There are two types: unglazed sugar moulds and glazed jars.

The sugar moulds helped to shape the sugar cones, which were then wrapped in blue paper and sent to grocers, who knocked off lumps of sugar with hammers and tweezers to sell to their customers. The smallest cones were used for the finest of the white sugar. The largest were used for the really coarse, grainy brown sugars.

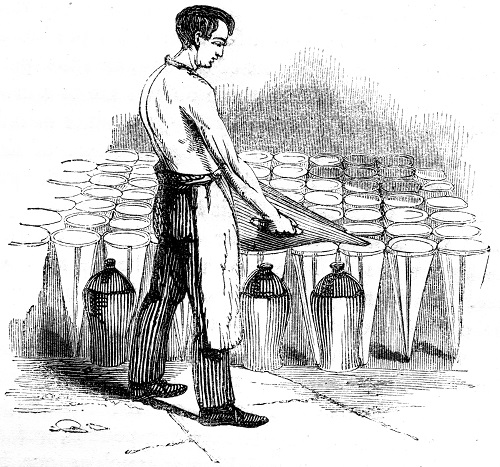

Sugar refinery worker using sugar pottery to refine sugar.

The glazed jars collected the excess syrup which seeped out of the moulds once the cone of sugar had formed. This syrup was boiled again and placed in a larger mould to make a coarser sugar. The excess syrup from that was boiled again, and again, each time producing a coarser browner sugar until only a thick black treacle was left behind.

The largest of the sugar moulds held 150lbs of sugar, equivalent to more than 130 large bags. This mould was known as a bâtarde in French, probably for a good reason as they would have been extremely heavy to carry to the upper floors of the refinery, maybe you can guess what the English translation is?!