Taki Katei's drawings: A Journey from Japan to Liverpool

The story of Drawing on Nature: Taki Katei’s Japan, began in the autumn of 1955, when a letter was addressed to the editor of the Museums Journal published by the Museums Association. The letter asked the editor to make it known that “a collection of several hundred [Japanese] sketches” in a private collection is available for “any museum or university that would like to accept them.” It was a generous offer, giving away sketches that were described as “quite beautiful.” These included many works by the then-long-forgotten Meiji era master of Japanese literati painting, Taki Katei [1830-1901]. This set of more than 400 sheets had been in the possession of one of Taki’s many pupils, Ishibashi Kazunori, who, as was the custom in Japan, had lived with his master for 5 years. Intriguingly, it was not Ishibashi who wrote to the editor.

To trace the background of this letter, we must travel further back in time to London and West Kirby in 1913. Ishibashi Kazunori, a Japanese artist who studied Western style portraiture at the Royal Academy of Arts in London [RA] from1905 until 1910, was negotiating with Katherine Florence Boult [1855-1927] over hundreds of sheets of Japanese drawings in the Summer of 1913. At the time, Katherine Boult was living in the Abbey Manor in West Kirby on the Wirral [then Cheshire] with her husband Cedric Randal Boult [1853/4-1950]. Ishibashi, then 37 years old, had many British friends, and Katherine Boult had excellent taste when it came to classical music and foreign fine art.

When Ishibashi arrived in London in November 1905, having first travelled around Europe in the early part of 1905, he brought with him a large bundle of his master’s drawings and studies from his studio in Tokyo. Taki Katei had passed away in 1901, having served as the Imperial Household Artist, the highest honour for a Japanese artist. As one of the favourite pupils, Ishbashi had “inherited the studies of the master.” After completing his studies at the RA in 1910, Ishibashi was a poor artist in need of funds, and in 1913, he decided to sell Taki’s drawings, with some of his own drawings and watercolours added to the bundle, eventually finding a perfect buyer in Katherine Boult who was sympathetic to his situation and was also a lover of Japanese fine art. Correspondence between them in July 1913 shows she was keen to help him by paying him a good price for the sketches, more than that offered by the South Kensington Museum [now the Victoria and Albert Museum]. She also promises the family would “treasure them always and that they will be a continual joy to us.” In admiration for traditional Japanese paintings, she also declares, “I do not care in the least for European art; one little picture of yours or your master’s is what I like far better, so to have this beautiful collection would be a great pleasure to me.”

Taki Katei’s preparatory sketches, World Museum, 56.50.18 and 56.50.95

Katherine Boult must also have admired the style of portraiture that Ishibashi learned at the RA from the master of the genre at that time – John Singer Sargent. During this correspondence, she also asks Ishibashi to do portraits of her daughter Olive and herself. Ishibashi replied, promising her that he would come to West Kirby by a night train to arrive in the morning of Saturday 26th to finish her portrait before the family’s imminent departure for Scotland. Katherine’s younger son Adrian was then studying at the Leipzig Conservatory, and it was not until 1923 when Ishibashi painted his portrait. Now referred to as Sir Adrian Cedric Boult, he became a conductor widely respected for his erudition and his precise and minimal baton technique. While being associated with a number of major orchestras all over the world, he also conducted many concerts in Liverpool throughout his life. Growing up in West Kirby as a musically talented child, Adrian was regularly taken by his mother to concerts at the Liverpool Philharmonic. His first orchestral concert experience was on Saturday 26th October 1895 when he was only 6 years old. After listening to “Siegfried’s Funeral March” from Götterdämmerung by Wagner, conducted by Hans Richter, he declared to his mother, “Oh I do like it, Mummie!”

Having been first exhibited at the RA, Adrian Boult’s portrait is now in the collection of the Royal College of Music with which he had a long and fruitful relationship. It is currently on loan to us for the Taki Katei exhibition. It shows him sitting at a table with his chin resting on his right hand, gently gazing towards the viewer, and wearing “his well-known chocolate coloured suit, rather than in those robes of a doctor of music to which he is entitled . . . ” The portrait clearly captured the characteristic modesty of the sitter.

Adrian Boult as a child playing a toy piano, courtesy of the Royal College of Music Museum.

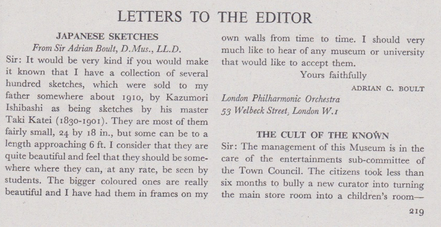

The sale of Taki’s drawings to the Boults was completed in 1913. Ishibashi then went on to create some of the most sumptuous panel paintings in traditional Japanese style for the London Hospital in 1916 [watch this space for another story on this]. Katherine Boult passed away in 1927, so she would only have had 14 blissful years with her treasured purchase. After his father’s death in 1950, Adrian Boult decided in 1955 to write to the Museums Journal, with an offer to gift the sketches that had given the family much joy for over 40 years. His letter showed his deep admiration for the drawings: “The bigger coloured ones are really beautiful and I have had them in frames on my own walls from time to time.”Boult must also have realised how much value and prestige these sketches would add to the collections of any serious museum.This sense of civic duty was important to him, as he also saw educational benefits of keeping the sketches in public ownership: “. . . [I] feel that they should be somewhere where they can, at any rate, be seen by students.”True to his modest and generous character, he did not put a price on them, nor placed any conditions or restrictions on their use. After suffering a huge loss of its entire Oriental collection during the 1941 air raids, the City of Liverpool Public Museums [now the National Museums Liverpool] was one of the first to write, on 7th November 1955, to the office of Adrian Boult at the London Philharmonic Orchestra.

Boult’s Letter to the Editor, Museums Journal, November 1955, Vol. 55 No. 8, p. 219 Sir Adrian Boult’s subsequent decision to entrust the entire collection to the then Director of the City of Liverpool Public Museums, Mr John Henry Iliffe, conferring him the responsibility to select some of the drawings to be divided up and distributed to three other museums, may well reflect his connection to and lifelong affection for the city that nurtured his love of classical music and ignited his ambition to become a conductor Ultimately, it was also a testimony to the professional integrity and judgment of Mr Iliffe and acting director Miss Elaine Tankard that the drawings have come to form an important part of the amazing collection at the World Museum Liverpool today.

Drawing on Nature: Taki Katei’s Japan is at World Museum until 13th April.