Uncovering the history of the Canning Graving Docks

The historic areas of our cityscape have a timeless feel – lulling us into a sense that they’ve always been as they are now, that they are unchanging. Our experiences of these places are often very different to those of people living in, working in, or visiting those places in the past. Heritage sites are sometimes accused of being ‘sanitised’ or ‘gentrified’: a side effect of making buildings stable, areas accessible and adapting use to modern needs.

The Canning Graving Docks are now a heritage site with the Edmund Gardner pilot ship situated within one of them. Historically they were a crucial part of the dock system, used to clean and repair ships between sailings, ensuring they were safe and as fast as possible when at sea. Soon after Liverpool's first dock, the Old Dock, was built, there was a need for graving docks because they were essential for the port and its merchants to be successful.

For Liverpool merchants, of course, success was often at huge human cost: much of the mercantile trade involved the trade in enslaved African people, abducted in West African countries and forcibly transported across the Atlantic. Through the 18th century around 200 merchants controlled this trade in Liverpool, and a further 1400 invested in them or were employed through them. A wider network of mercantile activity was built on slavery and the products of the work of enslaved people. Liverpool’s economy was so intricately linked to slavery that in 1806 it was described as ‘The metropolis of slavery’. The first graving dock in Liverpool - which now no longer exists - was built in 1718 and was overseen by Richard Norris who was a slave trader.

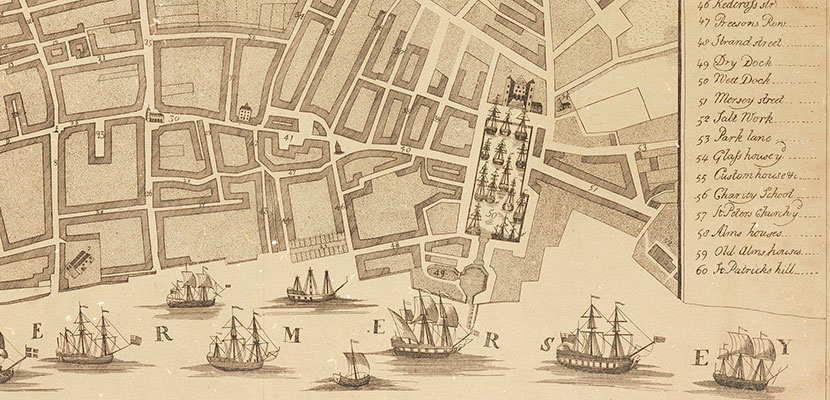

The present graving docks were originally constructed in 1765-9. Their 18th century roots make them the oldest surviving above-ground part of the Liverpool docks. They were in full use when Liverpool was at the height of its involvement in the trade in enslaved African people. The area around them was the site of a series of buildings, being adapted and rebuilt to suit changing needs. The graving docks themselves were lengthened and deepened in 1842 as the size of ships was increasing.

The Canning Graving Docks are old structures, but the way we see them now is very different to how they were in the past. It’s difficult to imagine them bustling with people: sheds on the quaysides being packed with cargoes, people working on quaysides making items for ship repair, boiling tar for caulking the decks, people working on ships, inside and out. Ships were readied for their next voyage, some heading to West Africa to be loaded with people being forcible transported to the Caribbean, America, and South America.

Navigating the dockside, visitors can take a moment to reflect on the historic structures of the graving docks, their history and legacy. The team at National Museums Liverpool is keen to understand and explore the roots of why these structures were built, the human suffering that is part of their story. This place is one of Liverpool’s direct links to the transatlantic slave trade.

Curators from National Museums Liverpool are working with the Liverpool Black History Research Group to research the history of the Canning Graving Docks: to understand the place and the people who encountered it. Like so many historic sites, the Canning Graving Docks hide a wealth of stories, and it is important to research and reveal that.