The weird and wonderful jobs of Pembroke Place

Today we have a guest blog from Richard MacDonald, a freelance historical researcher and Blue Badge Guide. Richard is leading a team of volunteers investigating historic street directories as part of the Galkoff’s and the Secret Life of Pembroke Place project.

Street sign for Pembroke Place

"Have you ever been in the awkward situation of finding yourself with a filthy ostrich feather and not knowing how best to clean it? No? Well... neither have I to be honest. However, if you were in in Liverpool in the 1890s and found yourself with a filthy feather, it would be reassuring to know that I could point you in the direction of number 5 Pembroke Place and the premises of Miss Emily Auger, Ostrich Feather Cleaner.

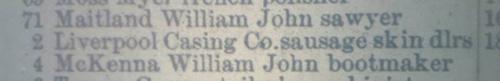

How do I know this? Well over the past few months I have been leading a team of volunteers exploring the Liverpool Street and Trade Directories to help us build a picture of the area around Pembroke Place and how it changed through time. It's during the course of this research we have come across some trades that are both amusing and baffling to modern eyes.

Street and Trade Directories are pretty much what you get on the tin, they feature lists of peoples' names and businesses in a town or city and often include lists of local churches, hospitals, civic buildings and other major public institutions providing an interesting insight into life at a particular time. Street directories started to become commonplace in the 1800s, however Liverpool is an early starter as its first directory was published in 1766 by John Gore. Unlike later directories, this is a simple list of names, arranged alphabetically and then by street. There are around a thousand names in the 1766 Directory over 76 pages. In contrast, by the time the 1900 Kelly's Directory was published it covered three volumes of over 2000 pages! Quite a feat for researchers to study!

Thankfully some directories are digitised online and using the magic of OCR (optical character recognition) it is quite simple to find the correct record with a simple text search. For those that were not digitised, a manual slog through the microfilm machines is in order. Unlike historical newspapers, directories don't give us any glimpse into the day-to-day lives of the people in Pembroke Place. You won't read about grizzly murders, jilted lovers or brawls in churches in the street directories but you may see the broader stories of an area and how they play out as the town grows and the suburbs expand. It's only in the first few years of the 1800s that we begin to see the name 'Pembroke Place' appearing in the directories.

Among the professions of those living in Pembroke Place are accountants, merchants, a solicitor, a goldsmith, a newspaper printer and numerous 'gentlemen'. It appears that in the 1820s, Pembroke Place was an area of genteel respectability. By the 1850s the character had changed, although there were still the occasional 'gentleman' in the directory there were a lot more provision dealers, grocers , tailors and drapers – what in the parlance of the day would be called 'in-trade'.

The area was also beginning to develop a medical air – perhaps from the nearby location of the Liverpool Infirmary. Surgeons, dentists and a 'Lying In Hospital' are all features of Pembroke Place in these years. Where there is medicine, you often find quackery and one particular character from this period was William Dawson Bellhouse, 'Professor of Electricity and Galvanism, 17, Pembroke Place'. It is unlikely William Dawson Bellhouse was a recognised 'professor' and his galvanic treatments largely consisted of administering 'electrical baths'. Shocking stuff!

We can tell from his rather unusual profession, that William Dawson Bellhouse may be a person of some interest – after all – 'galvanism' isn't something you come across every day. However this does highlight a weakness of street directories, for every 'Professor of electricity and galvanism' or 'ostrich feather cleaner' you have a Joseph Sanders. Joseph Sanders (7 Pembroke Place), would become a key player in the evolution of the railway system. But here we come to one of the drawbacks of directories, from his entry, there is no way we can tell that he was 'the man who found George Stephenson' and the main campaigner for a Liverpool-Manchester Railway. Unlike Dawson Bellhouse or Emily Auger – forgotten people now of interest because of their unusual trades – Sanders as an important financier and campaigner is reduced to a humdrum 'Corn Merchant' by the directories.

Directories can be useful, but there is a lot they leave out. Something else that they glaringly leave out is those people who are not considered 'principal inhabitants or trades' – i.e. the poor. It is notable that in the original 1766 directory there were only 1000 names, yet at the time Liverpool's population was over 30,000. We know that by the 1850s, the two courts behind Pembroke Place were built and inhabited, previously they were known as Watkinsons Buildings and Watkinsons Terrace, by the 1850s, they were known as Court No. 1 and Court No. 3. They do not appear in the directories. As with any historical source it is important to realise that you are getting an edited version of history. This is especially important when it comes to directories- they were commercial publications, there was no legal requirement for accuracy (unlike a census) and as they were published yearly they could be out of date as soon as they came out. Our volunteers are still compiling lists of the most unusual professions of the area and I'm sure you'll see a list of them in due course!

Now, I wonder where I can buy something to hold my sausages together!"