What is Terrace Culture? And who are Casuals?

Kevin Sampson gives an overview of what Terrace Culture is and how important Fashion was to football fans of the 1970s.

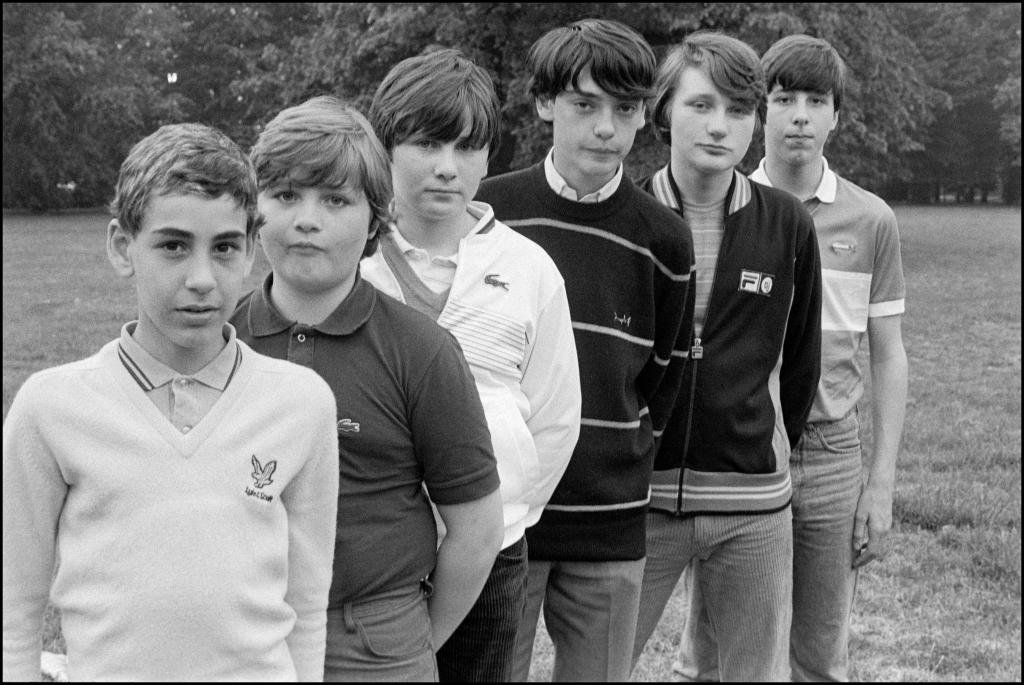

Image: A group of young East London Casuals, featured in an article in The Face magazine, 1983. This was the first time that the term Casuals was used by the media to describe the movement, some six years after it first developed in North West England. They wear a number of Casual-related brands, including Fila, Lacoste and Ellesse. Copyright David Corio

You’d be forgiven for thinking that UK cloth manufacturers had a stake in the fashion industry in the mid-70s. Trousers were ludicrously wide and football fans carried at least two scarves, worn on either wrist, each team proudly wearing their colours. Wherever you went, from Newcastle to Ipswich, you’d encounter gangs of angry locals with Bee Gee hairdos, big boots and flapping trousers.

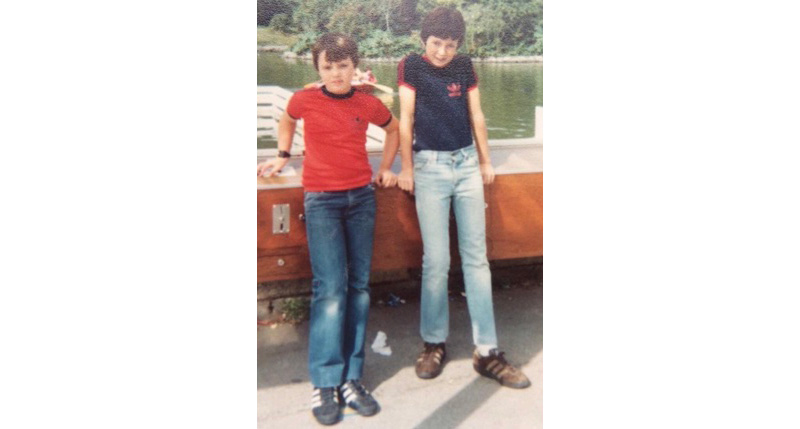

In that context, it really was the shock of the new for the 15-year-old me, sat on the grass banks outside Wembley before the Liverpool v Southampton Charity Shield match in August 1976. Emerging from a sea of denim, hair and bovver boots came a little gang of younger lads – only about 10 or 12 of them – all wearing suede shoes, narrow jeans, those Adidas t-shirts with the embossed plastic shoulder stripes. Importantly in an era of centre-parted bouffant hair styles, these lads had short hair in neat side-partings. Over the next few seasons, I came to recognise many of those young faces as the nucleus of Liverpool FC’s Anny Road crew – the first gang of football fans to move away from the Boot Boy look and start a revolutionary new trend in Terrace Culture. These were the first-ever Football Casuals.

Not that they ever called themselves Casuals – that term was coined by the London media in the 80s to embrace a cult that had risen up from the streets to dominate high street fashion. This emerging scene was mercurial rather than casual, with a certain brand or item being deemed ‘In’ one week and ‘Over’ the next. The roots of that cult with no name were firmly embedded in Liverpool and, for those first fledgling years of The Look, it was very much a Merseyside thing.

Why Liverpool? There were soon to be Manchester’s Perry Boys and regional variants all over the country – but the consensus is that this unique, ever-changing scene originated on Merseyside. One theory is that, with Liverpool FC reaching a European final every year from 1976 to 1978, their well-travelled fans were able to pick up rare sports shoes and fashionwear on the road. There’s no doubting this was a factor, but there’s also a generic contrariness that runs through the Scouse DNA. Liverpool was the only major music city in the UK not to have an out-and-out punk band, and there’s always been a nonconformist tendency. This new chapter in terrace culture was as much driven by the city’s almost wilful need to innovate and stand out from the crowd as it was by regular access to elusive European design lines. The phenomenon that emerged in the late 70s - the Liverpool Look – grew into a lifestyle for many, and ultimately changed the way football fans dress and behave.

During the 1977-78 football season that initial look was a magpie’s collection of items and details gleaned from other cultures and different countries, grafted onto a solidly streetwise, smart individualism. The early manifestation involved a hybrid of punk styling (mohair jumper/drainpipe Lois jeans,) the fawn duffel coat and androgynous wedge haircut that Bowie modelled in The Man Who Fell to Earth, along with a range of utilitarian footwear including adidas Samba training shoes, ribbed corduroy shoes with galvanised rubber soles, yachting pumps, Kickers and Pod – depending on the time of year.

A glance at Liverpool’s Cup fixtures that season illustrates the diversity in terrace wear among different regions and fanbases during that embryonic 77-78 season. In January 1978, LFC had a two-legged semi-final against Arsenal, with the Londoners’ following taking up half of the Anfield Road terracing - a two-ply police walkway separating them from the Liverpool fans. That packed end showed a marked contrast either side of the divide, with a proliferation of duffel coats and dangling fringes among the young Liverpool lads. And, while the Arsenal contingent had its wedge-heads and smoothies, the most sizeable element among them were skins in Harrington jackets, as well as a good few punks and the ubiquitous older guys in sheepskins and donkey jackets. A few months later Middlesbrough visited in the FA Cup quarter final and were, by and large, still feeling the width. Full length white butcher’s coats (replete with marker pen slogans,) parallel jeans and DMs were staples of the uniform for Boro’s away following back then, with lots and lots of scarves. By contrast, fans of Liverpool, Everton and Tranmere Rovers would regularly be goaded for their lack of club colours, or more generally for “looking like girls.”

As we moved towards the end of the 70s, the staples of the scene changed. Inega and Ciao took over from Lois as the must-have jeans and cords (with Fruit of the Loom bib and brace having a moment, too.) And, having been the scene with no name for so long, we started to hear the young match going Scousers who pioneered the look refer to themselves as Scallies or Scals. Younger Scals wore snorkel parkas, Clark’s Nature Trekkers, Lee cords, Slazenger jumpers, Fred Perry t-shirts, Samba or Mamba training shoes. Their female equivalents wore kilts, knee-length stockings and Kickers – along with the ubiquitous, Cyclops fringe hairstyle. Older, slightly more affluent kids started getting into Adidas’s ‘tennis’ range – Stan Smith, Lendl, Nastase, Rod Laver, Tom Okker and the Holy Grail of them all, Forest Hills – worn with striped Peter Werth polo jumpers. This was still largely a Liverpool thing, so dynamic and self-renewing that little indie shops sprung up all over the city centre, catering to the unquenchable need for newer, more exotic fashions. Some stores lampooned the madness: one of them, Patches, had signs in its window announcing: “In for one week only – burgundy jumbo cords. Another one said: “Why go cold? Snap up those sensible 3-star jumpers NOW!”

Yet as we entered the new decade, what had been a burgeoning movement became a runaway train, with every city and team, from Aberdeen to Plymouth having its hardcore of Dressers. There were still regional differences, but they were variations on the same theme – one team might wear Adidas Gazelle where another favoured Barrington Gold or Diadora Borg Elite. In an era before the instant news of Instagram, young bucks had to travel far and wide to see what their rivals were wearing – that, along with their monthly fix from mags like 'The Face' and 'The End'. But as a new breed emerged, the cult with no name was finally baptised. 'The Face' ran a spread about kids in Benetton shirts, Fila Bj jackets, pastel shades of Lacoste and Ellesse and cords with a two-inch slit at the ankle, and dubbed them Casuals. The name has stuck – and the scene lives on.