Who was China's First Emperor?

Discover the story of China’s First Emperor, Qin Shi Huang.

Qin Shi Huang was born on 18 February in 259 BC. Famed for his army of terracotta warriors built to protect him for eternity, the Emperor is also one of the most controversial figures in history. Seen as a visionary by some and a tyrant by others, his achievements in such a short space of time were nevertheless remarkable and far-reaching. Here we take a closer look at the life of the man at the heart of our landmark exhibition.

An early achiever

A life of conquest shaped the man who would become China’s First Emperor. Born Prince Ying Zheng, he was just 13 years old when he became King of the Qin State in 246 BC. Initially supported by his mother Queen Zhao Ji and chancellor Lü Buwei who effectively managed the government, the young king took full control of his kingdom aged 22. With massive armies he overpowered the six remaining independent kingdoms of the late Warring States Period and unified China in 221 BC; putting an end to centuries of political turmoil, constant war and endless bloodshed.

Cosmic ruler

Ying Zheng saw himself differently. When he unified China he also claimed the mandate of Heaven by inventing a new title inspired by the divine rulers of Chinese mythology: Qin Shi Huangdi. Qin after his native state; Shi meaning ‘the first’ and so proclaiming the establishment of both an empire and a dynasty; Huang meaning ‘august’ after the name of three mythical kings and di meaning ‘divine ruler’ after the five sage emperors that followed those kings, according to Chinese legend.

Reform and innovations

Quickly abolishing the old feudal system where the inheritance of titles had led to much corruption, Qin Shi Huang appointed officials to administer his new Empire based on their ability and achievements. Once political reforms were in place, the Emperor turned his attention to economic and social changes to improve communication, administration and trade.

Banliang coin mould, Warring States Period. Image © Mr. Ziyu Qiu.

The Qin state already produced banliang coinage around 100 years before it became the standard currency across the First Emperor’s new Empire. A unified system of weights and measures was introduced, a single currency was adopted that is still associated with China today, and writing was standardised into a script that could be read throughout the Empire. Even the axle widths of chariots and carts were made uniform so that travellers could use any road.

Absolute power

The Emperor ruled by control, fear and punishment. His harsh reign followed the philosophy of Legalism which was based on the idea that people are more inclined to do wrong than right because they are motivated by self-interest. Eventually, the Emperor banned all other philosophies such as Confucianism and Daoism that had flourished during the Warring States Period, and ordered the burning of texts that did not support Legalist views. It is said he may have even executed writers, philosophers and scholars to silence opposing voices. Unsurprisingly, the Emperor’s actions attracted many enemies and several assassination attempts on his life were made.

Ambitious building projects

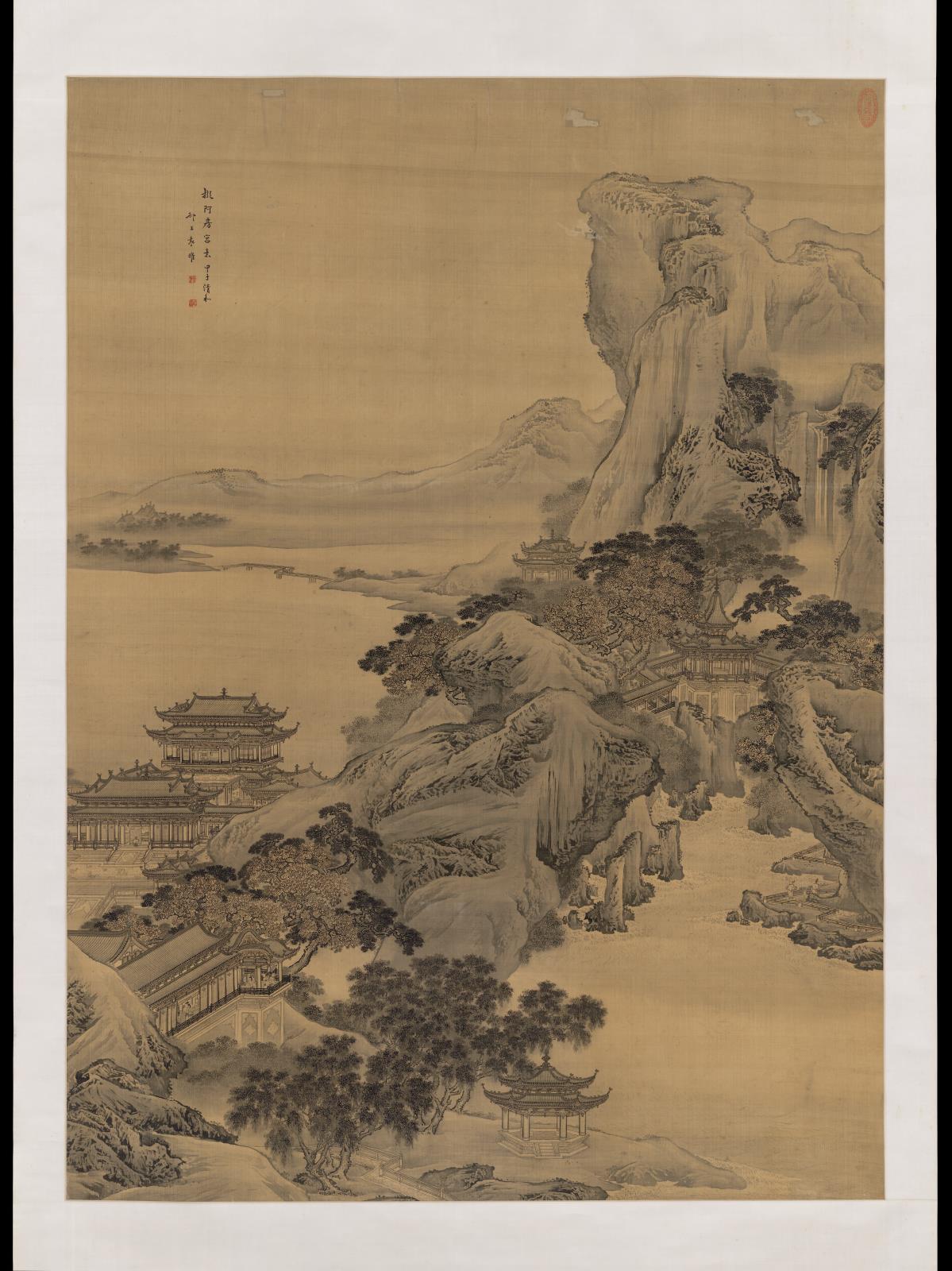

An imagined view of the E-pang Palace. Chinese, Qing dynasty, Qianlong period 1744.

Yuan Yao (Chinese, active around 1740–1780). Strict laws and severe punishments meant the Emperor had a ready supply of convict labour to embark on his ambitious building projects. New road and canal networks were introduced to improve trade and travel, and a precursor to today’s Great Wall of China was built to create a single defensive system against northern tribes. The Emperor also had hundreds of luxurious palaces built in his capital at Xianyang to house his concubines, children and servants. According to the Han historian Sima Qian, the most magnificent of these was E’Pang Palace, with a front hall alone measuring more than 75,000 square metres and terraces that could seat 10,000 people. Although there is no clear archaeological evidence to show it ever existed, it has become legendary as the biggest and most sumptuous palace ever created.

Quest for immortality

As he grew in power, China’s First Emperor became obsessed by death and the desire to become immortal. He sought magical potions that would guarantee eternal life and regularly consulted magicians and alchemists. He even organised expeditions to the East China Sea in search of the mythical ‘Islands of the Immortals’, with the hope of finding herbs and plants to bring him immortality. Ironically, the Emperor’s attempts to live forever may have contributed to his early death at the age of 49, as some of the elixirs he drank contained mercury.

Image: Bronze goose, Qin Dynasty. Excavated in 2000, First Emperor’s Mausoleum Site. Image © Mr. Ziyu Qiu

This goose is one of 46 birds discovered with 15 terracotta musicians in a pit near the Emperor’s mausoleum. The pit was designed to represent an imperial garden with geese, cranes, swans and musicians for the enjoyment of the First Emperor in the afterlife.

A hidden empire

Even though he failed to conquer death, the Emperor had grand plans for his afterlife. In a bid to secure his position as cosmic ruler, he commissioned an entire kingdom to accompany him to the next world; unlike anything seen before or since. With his tomb at the centre, the Emperor’s lavish mausoleum is said to have housed a kingdom of riches for the afterlife and was secretly guarded by his now world-famous terracotta army. This underground kingdom came at a considerable human cost though, and a large number of human remains have been found across the Emperor's burial site. Historical documents record that “thousands of officials were killed and thousands of craftsmen were buried alive…to keep the tomb a secret”.