Why Jeremy probably wasn’t the perfect pet

The Life on Board gallery in the Maritime Museum features the story of one very distinct character – Jeremy, the well-travelled kinkajou from Chile, purchased in the 1960s by seafarer Robert Ng. Jeremy subsequently travelled the globe, providing companionship to Robert on the ships he worked on, before returning to the family home in Liverpool. While Jeremy led a good life, his story does highlight the importance of animal welfare and difficulties in caring for exotic species.

Jeremy the kinkajou in Liverpool with a member of the Ng family

What is a kinkajou?

Kinkajous, also known as Potos flavus, are tropical mammals native to Central and South America. They eat a variety of fruits, insects and nectar. Kinkajous evolved ‘independently’, meaning they do not have many closely related species in existence today. Although not currently nearing global extinction in the wild, kinkajous are captured for the pet trade and hunted for their fur and meat.

Kinkajou on display in the Life on Board gallery

Restrictions on importing animals

Jeremy’s owner Robert noted that when he brought Jeremy home to the UK in the 1960s, he was only requested to keep the kinkajou away from farms and livestock to avoid the spread of disease, but there were no further restrictions on bringing such an exotic species into the country.

Much has changed since the 1960s. If Robert was to import Jeremy now, he would need to travel through an allocated Border Control Post. In England, Jeremy would most likely enter via Heathrow airport with a visit to the Animal Reception Centre. The kinkajou would then be checked by veterinarians for disease and enter a period of quarantine. Further authorisation from the Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA) may also be required.

Some populations of kinkajous in Honduras are threatened with local extinction due to capture for the wildlife trade. If importing from a restricted country, CITES licenses would be required for the trade to be legal. CITES is a permitting system and international treaty used to ensure the trade in plants and animals does not cause wild populations to go extinct.

These restrictions are also in place to ensure the biosecurity of the UK. Such biosecurity measures are in place to limit the spread of disease and invasive species that could potentially devastate the UK’s farming and fishing industries and cause harm to native wildlife.

Caring for kinkajous

The importation rules may have changed since the 1960s, but kinkajous are still considered an unusual pet today. Kinkajous are nocturnal, very curious and dislike loud noises and sudden movements. Their natural behaviour and human lifestyles are significantly different - meaning ‘pet’ kinkajous are often not happy in the average household.

Kinkajous are arboreal meaning they are tree-dwellers. To be kept happy in captivity they need a very large space with plenty of climbing opportunities. They are a long-term pet, living an average of nearly 30 years in captivity. Another challenge of keeping kinkajous is finding specialist veterinarians that could provide adequate care. Bills from such specialists tend to be very expensive.

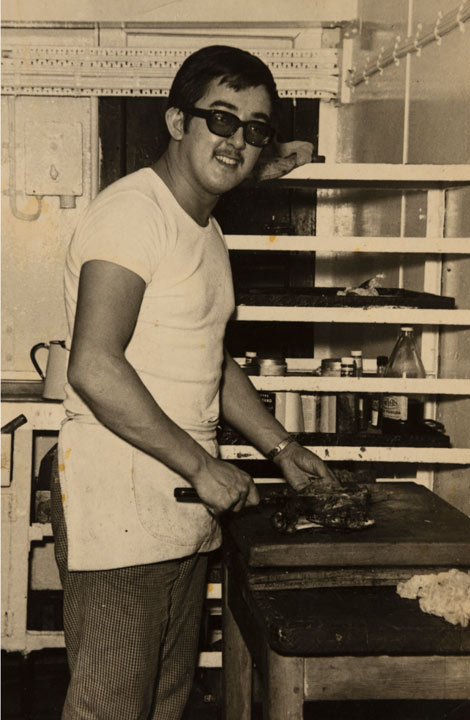

Robert Ng, the ship's cook and owner of Jeremy the kinkajou, working in the galley

Despite Robert and Jeremy having a close bond, Jeremy was still rather destructive. He regularly clawed at the furniture on-board the ship and even squeezed toothpaste all over Robert’s cabin!

There are many accounts of kinkajou owners receiving deep bites and scratches from their ‘pets’. Ultimately, kinkajous are wild animals that can, on rare occasions, be tamed. They are not a domesticated species and are best suited to life in the wild. Kinkajous can be found in Central and South America, as well as in many zoo collections.

Life on Board

If you wish to see a kinkajou up close, as Robert did recently, visit the gallery Life on Board in the Maritime Museum, where a kinkajou from World Museum’s collection is now on display. This is not the original Jeremy, but Robert thought it had a close likeness to his former pet when he visited.

Robert Ng visiting our taxidermy kinkajou in the Life on Board gallery