A woman navigating a STEM career in the 18th century

Lead image: Double reflecting octant made by Ann Smith of Liverpool c1788-1800. MMM.2007.173

From the earliest ocean going craft to today’s enormous container ships, navigation has been key to the history of seafaring. The ability to plot your position on a chart relative to where you were going has long been an essential part of safe passage. The science of navigation has improved seafaring, has saved lives, and has helped human beings to map the world with ever greater accuracy.

The object pictured here is a Double Reflecting Octant, in its day the most accurate way to plot a ship’s latitude ever invented. This particular Octant dates from around the end of the 18th century and was made right here in Liverpool by Ann Smith, who ran a navigation shop in Pool Lane. Ann is unusual in that she’s a woman engaged in the scientific instrument trade in the 18th century whose name we know and whose work we have an identifiable sample of. It was a male dominated trade and what women were involved, and it’s impossible to be sure of numbers, have mostly not been recorded. Ann’s husband died in 1788 when her elder son was just 14, leaving her a single mother with two children. A contemporary advert from this time shows her announcing her intention to carry on the family business.

“ANN SMITH (Widow of the late EGERTON SMITH) begs leave to inform her friends and the Public that she carries on the Business of her late HUSBAND, in all its Branches, and as she employs the best Workmen, and pays every attention to the Undertaking, flatters herself with the hopes of their continued Favors, which will ever be gratefully acknowledged.”

Though the business was previously registered in her husband’s name this doesn’t mean Ann had no part in it prior to his death, indeed that seems quite unlikely as historian Helen Doe points out:

“Longevity is a real problem in the discussing of businesswomen as it raises the vexed question of the hidden contribution of wives who supported their husbands. Who is to say which of the partners was the most active? To just measure longevity by the date at which a woman takes over an enterprise is to undervalue what may have been occurring for some time. A total absence from the concerns of the business hardly led to a successful transition in widowhood.” - Helen Doe, Enterprising Women and Shipping in the Nineteenth Century

It certainly seems to have been a successful transition. The business was well established when she took over, begun by her husband in 1766, and seems to have been well known in the city. We can see this in a notice from the Theatre Royal, Liverpool’s main theatre in the late 18th century, in Gore’s Advertiser in 1795 which states that tickets are available from ‘Mrs Smith’s Navigation Ship, Pool Lane’. The business continued under Ann’s name for nine years until her eldest son, also called Egerton, joined her in 1897. They traded as Ann & Egerton for three years before Egerton went into partnership with his younger brother William. Having run the business on her own for the better part of a decade, was Ann using this time to show him the ropes before he took over? Her continued input in the business suggests more than a mere caretaking role until her son was old enough to step in. Instead this partnership at the start of her son’s career seems more a preparation to hand over the reigns, allowing him time to work with someone experienced in the business.

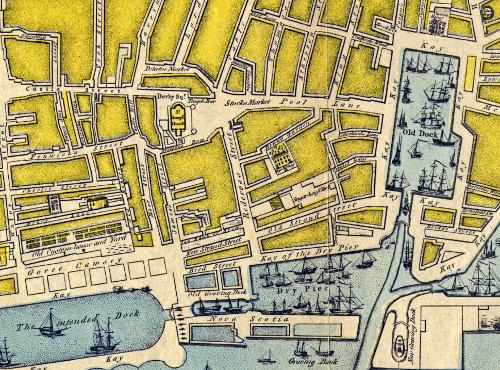

A section of the Eyes Map of Liverpool, 1765.

If you look at the Old Dock you can see Pool Lane running away from it to the left. The area round the Old Dock and Pool Lane is now part of the Liverpool One shopping centre. Anyone familiar with Liverpool may well be struggling to place Pool Lane as the road itself no longer exists. It was one of Liverpool’s oldest streets, ‘Pool’ referring to the original pool from which the city takes its name and which by Ann’s time was the Old Dock (the world’s first enclosed wet dock). Pool Lane ran from what is now the Victoria monument (the site of St. George’s Church in Ann’s day) to the Old Dock and was renamed South Castle Street in the late 1830s. It disappeared as a street entirely with the Liverpool One development in the first decade of the 21st century. Ann’s shop would have been somewhere in Liverpool One and it would have been just as prime a piece of retail estate then as it is now. The street led right to the Old Dock, still in use at this time, and an area bustling with seafarers and maritime industries, a perfect location for a shop selling navigational instruments and charts. The time in which she’s heading up the business is also an exciting one, not just in Liverpool which was fast expanding but for women more generally.

In 1791 the French playwright and political activist Olympe de Gouges published the 'Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen', criticising the failure of the French Revolution to produce equality for women. Then in 1792, a little closer to home, Mary Wollstonecraft published ‘A Vindication of the Rights of Woman’, her famous text in which she argued that the only thing keeping women inferior was the lack of education afforded to them and argued for a society which treated both men and women as rational beings. Whether she was aware of these women and their works or not, Ann Smith was alive and working in a technical profession at what could be described as the start of the modern Women’s Rights Movement. In a world where we still struggle with the gender balance in STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) careers she’s not just a trailblazer for her time, she’s still pretty impressive by our own standards.

Drawing of Ann's eldest son, Egerton, from the Walker Art Gallery's collections. - WAG 10750

This is a single mother who ran a successful business in a prime retail area, while raising two children and managed to provide well enough for them that her eldest had the financial and social capital to found a successful newspaper. In 1808 her son, Egerton, founded the Liverpool Mercury, a newspaper that would run for more than 200 years. It was known in its final years as the Liverpool Daily Post following a merger in the early 20th century. Contemporary sources show him on committees with the likes of Edward Rushton and Joseph Sanders (a wealthy Liverpool corn merchant), demonstrating his social standing in the city. The site of Ann's shop might still be a popular retail area but otherwise she'd find the port of Liverpool unrecognisable. The size and security requirements of modern ports have pushed them ever further out of city centres, and merchant seafarers ever further out of public consciousness. It was for this reason that Merchant Navy Day was created in 2000 to raise greater awareness of the industry that still brings us in UK more than 90% of everything we use.