You’re on Mute

Tech and Trafficking: a complex relationship

On 23rd March 2020, the lives of those in the UK became largely virtual as the first national lockdown in response to the COVID-19 pandemic began. A significant proportion of workers and students were required to work from home – some fortunately could take home office equipment, and others were balancing laptops on the edge of makeshift desks. Meetings around tables, classrooms and lectures soon became a bunch of heads and shoulders on screens.

Photo by Chris Montgomery

And that was just the employment and education aspects of our lives, our social lives turned largely virtual too. Many of us over the weeks and months of lockdowns would have countless quizzes and ‘pub nights’ over video calling platforms, we would be playing games through screens and shopping for those ‘essential’ items at the click of a button.

As we navigate an increasingly virtual and technology focused society, it can provide us with a moment of reflection to consider the realm of tech from the perspective of contemporary forms of slavery. We can do this by considering the production and delivery of technology items, through to its use in abusive and empowering senses.

Supply Chains

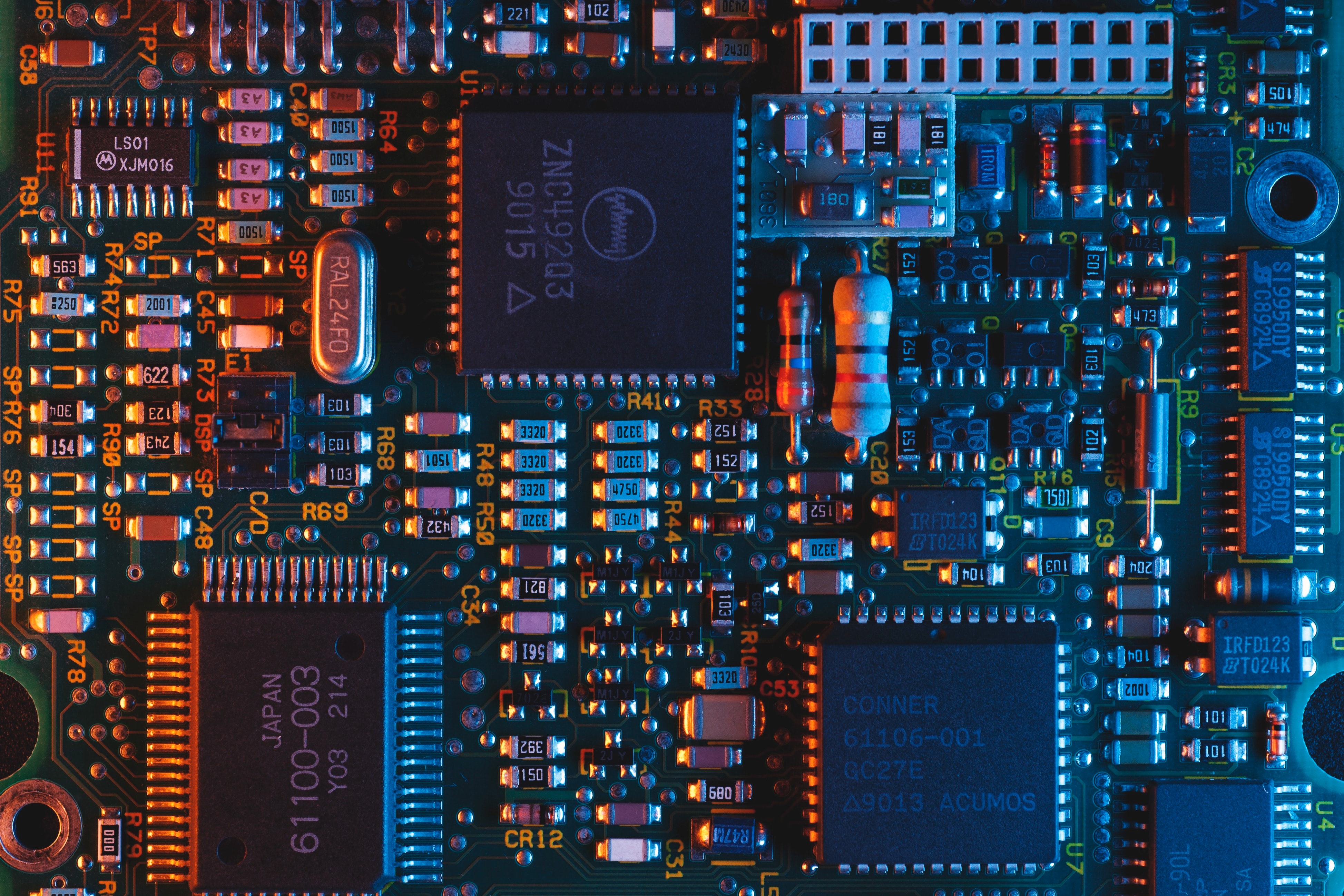

Supply chains of nearly every product in existence is tainted with contemporary slavery and other forms of labour exploitation. And this is true for technology from the mining of raw minerals, through to construction of electronic products and delivery. Research shows that tungsten, tin, tantalum (coltan), and gold, all used in electronics products, are produced with forced labour in places such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The production of electronics and their parts takes place mostly in Asia and Southeast Asia. Migrant workers constitute a significant proportion of workers in electronics supply chains and are considered particularly vulnerable to exploitation. They might not be familiar with the culture and language of the country they are in and may not be aware of their labour rights or have the ability to exercise them.

Photo by Umberto

In the warehousing and distribution sector in the UK, it is common for companies (59%) to use agencies to employ workers and recruitment of non-UK EU nationals is more common in this sector than average. Some suggest the use of agencies may lead to increased likelihood of employment rights breaches, for which there is a notable spectrum of non-compliance with forced labour and slavery at one end of this. The COVID-19 pandemic has meant the global electronic industry has faced a dual impact. With many people facing restrictions on going into work, there was a global unavailability of workforces in the production and logistics of electronic supply chains, leading to a gap in the demand and supply of products. Many people voiced how businesses must not lose sight of their business and human rights commitments as they manage their response to the pandemic.

It has been widely reported that workers in less protected and low-paid jobs, particularly migrant workers, are disproportionately affected by the pandemic via job loss and pay reductions for example. Many migrant workers are also impacted by limited access to healthcare and overcrowded or substandard accommodation, meaning their risk of contracting coronavirus is exacerbated due to lack of hygiene and social distancing practices available.

Connections and a digital divide

The pandemic induced new virtual ways of working and socialising, leading to some businesses growing rapidly. The popular video-calling platform Zoom saw its revenue increase by 355% May-July 2020 and saw its customer base grow by 458% compared to the same three-month period in 2019. This growth in usage of technology compatible with video calling also highlighted a digital divide and disjointed connectivity with some members of our communities.

Most of us have probably said (or been on the receiving end of) ‘you’re on mute’, but how many of us have considered this well-versed line within a wider context of contemporary forms of slavery? Many of us can easily click the unmute button, joke about how we should have got the hang of this video-calling malarky by now and carry on. However, victims of contemporary slavery may feel muted, or like their voice, autonomy and identity has been suppressed or even removed by their exploiters that is not as easy to overcome.

Prior to contemporary forms of slavery, during recruitment stages, technology can be used to post deceptive job adverts and has been reported to being used to sell humans in what has been described as an online slave market.

During cases of contemporary forms of slavery, it is known that exploiters often take mobile phones from the victims. This technological isolation can remove agency and independence with things like their ability to call for help, accessing maps to find directions to safety, translating words into a language they understand. Actual and threats of violence, instilling fear, intimidation, humiliation and other degrading controlling tactics from human traffickers and slave drivers can also contribute to someone feeling unable to voice, speak against or disclose to someone else about the exploitation they are being subjected to.

Photo by Priscilla Du Preez

Survivors and Tech

Following exploitation, a survivor of trafficking often relies on a phone, like we all do, to make health appointments, to connect with friends and family and to carry out tasks such as using alarms and reading the news to keep up to date with things like new pandemic restrictions regularly announced by the government. Survivors of trafficking and slavery in the UK also depended on electronic equipment like phones, tablets and laptops to stay connected with support workers who had to stop or significantly reduce the amount of face-to-face support visits.

Many survivors also take to utilising technology and social media platforms as activists. These survivor-advocates often talk about their life and campaign for a better future for themselves, other survivors and around prevention initiatives.

Other survivors are being empowered and participating in educational opportunities to become software engineers. An example of this is AnnieCannons based in California. AnnieCannons provides a phased programme for survivors of human trafficking and gender-based violence, starting with understanding data literacy, moving onto learning programming languages, and lastly encouraging the students to build software products themselves to solve problems they see in the world.

Tech Against Trafficking is an organisation that highlight another perspective regarding how technology companies can play a major role in preventing and disrupting human trafficking. Tech Against Trafficking have found over 200 anti-trafficking tools - around 69% of these tools work to identify victims and manage risks of child and forced labour in supply chains. However, they also found that there is ‘a strong concentration of tech tools developed and operating in the Global North, despite higher prevalence rates of human trafficking in the Global South’.

Some other technological advancements include the use of satellite imagery to identify things like fishing vessels and brick kilns that are exploiting people for labour. The Rights Lab team at Nottingham University are fighting slavery from space and by using the high-resolution freely available satellite data, cross-referenced with on-the-ground knowledge, they can better target the fight against contemporary slavery.

What can I do?

There are also things that you can do with your own technology access to make a positive impact in this area of contemporary slavery and trafficking.

Some actions you can take as the general public and consumers of electronics include checking modern slavery statements of big companies before purchasing, writing to companies who you do not think are doing enough to eradicate slavery, trafficking and forced labour from their supply chains to encourage large-scale change. You could also donate electronics you no longer use to organisations supporting survivors who are experiencing a digital divide that may be hampering their recovery and regaining of autonomy (check their acceptance criteria first). You could also utilise your own electronic devices to help with spotting signs of slavery and trafficking and reporting concerns through apps (such as Safer Car Wash, Farm Work Welfare and the Unseen App).

Just from this short blog you can see how technology and contemporary forms of slavery has a complex relationship that spans the spectrum of exploitation through to empowerment. Technology is used for recruitment, control, identification and in the recovery needs of survivors, to name a few. This list in reality in much longer and nuanced, and it will continue to grow as we make further technological advancements.

Find out more:

Tech company tools to fight human trafficking

Laptop firms acused of labour abuses against chinese students

Digital divide isolates and endangers millions of uk poorest