Digging for the dock’s past

Alongside the recent Piermaster's Green community excavations in the heart of Liverpool's historic docks, we took a look at the lives of the families who used to call the waterfront home.

Walking along the Liverpool waterfront surrounded by impressive architecture both old and new it is easy to forget what is missing from the picture. 175 years ago when Prince Albert officially opened the Albert Dock not many would have pictured a story which included the bombing, abandonment and silting up of the docks before regeneration brought a new lease of life to the waterfront.

Three of the buildings destroyed during the Liverpool Blitz of the Second World War include numbers 7, 8 and 10 Albert Parade which were located next to the Piermaster’s House, number 9 Albert Parade. Built in 1852, these houses were homes to the piermasters and dock masters who worked on the docks along with their families.

Albert Dock and the Canning Half Tide Dock, Liverpool, 1920. The houses at Albert Parade can be seen on the waterfront by the Albert Dock. EPW003066 © Historic England

Uncovering new stories

In summer 2021 the Museum of Liverpool archaeology team investigated the site of numbers 7 and 8 Albert Parade as part of the Piermaster's Green community excavation to find out more about everyday life on the docks. The following summer they returned to the waterfront to focus on the sIte of numbers 8 and 10 Albert Parade.

Archaeology is the study of human activity in the past, by studying the evidence yet to be uncovered, the buildings themselves and material remains, we can discover more about the story of the ordinary and extraordinary people of Albert Parade. But why excavate a site which is remembered and not ancient, what could we possibly find that we don’t already know?

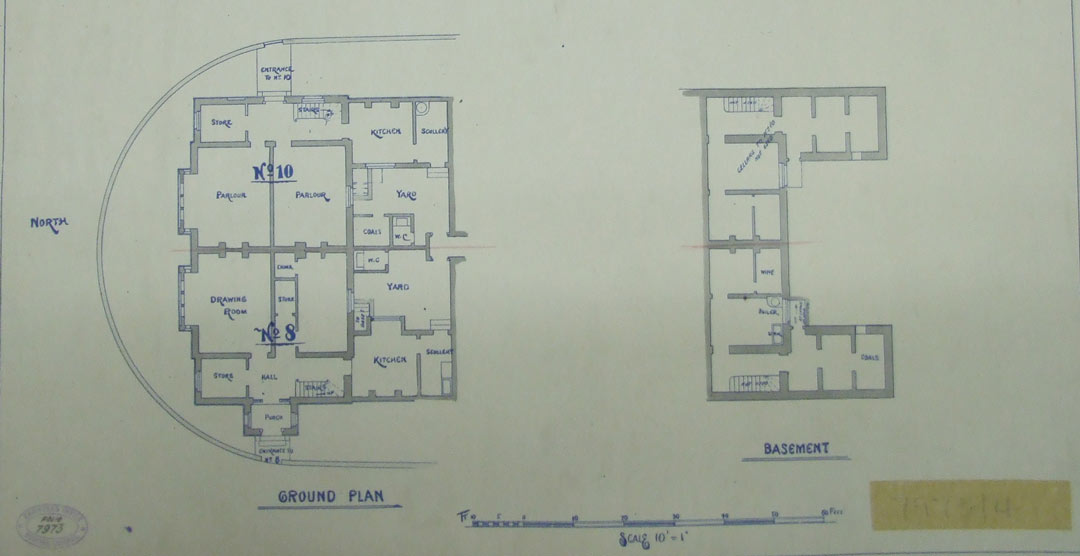

We have some fantastic drawings which tell us the layout of the buildings, so unlike the Romano-British houses excavated at Irby, Piermaster’s Green wouldn’t give us too many surprises. However there is always something new to discover. The story of the docks often focuses on its maritime history or the lives of the dock workers, but other stories remain to be told. By investigating these family homes we could get a glimpse of what life was like for women and children living on the docks.

Architects drawings of the layout of numbers 8 and 10 Albert Parade

Memories of Albert Parade

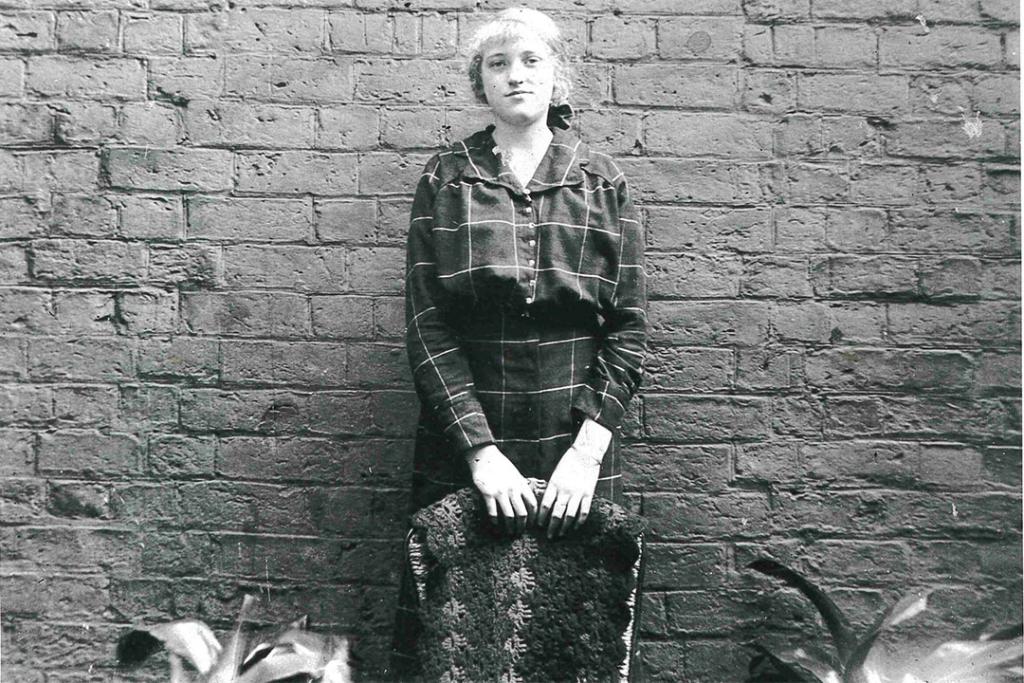

Mrs Parry (pictured above), daughter of William Henry Wilcox, lived at 8 Albert Parade between approximately 1901 and 1920. She talked about her life there in an oral history interview recorded by National Museums Liverpool on 17 August 1982.

"The houses all joined in a circle: but the gardens were separate, nothing would grow in the gardens except for Nasturtiums, Prince of Wales Feathers and an Elderberry Tree...

At Christmas time they used to get gifts from the trawlers of cases of oranges and turkeys, off the little boats they got gifts of wine and soap and rum. Everybody in the house liked rum. When anybody had a cold mother used to make a basin of gruel, a noggin of rum, some butter and nutmeg which was a cure for colds. Mother also used to preserve the oranges in rum for use later in cakes."

Filling in the gaps

Often assumptions can be made when we investigate historical sites where written sources are available, however archaeology can fill in the gaps and tell the unwritten stories. In some cases archaeology can also challenge the written sources and biases recorded through them, as we discovered through the 2018 Oakes Street excavations where objects of seemingly higher status were recovered from an area that was known in the written sources as ‘slum’ housing.

When soil conditions are dry, organic materials rarely survive and so details of the comfort of home often remain missing from the archaeological record. In some cases of historical archaeology, we can turn to oral history to add colour and comfort to the evidence. The transcript of Mrs Parry’s interview records:

"Mrs Parry’s mother was a good needlewoman. She made patchwork quilts for the beds from brightly coloured dress cottons, and lined them with calico. She made wadding quilts for winter use. The wadding was covered with linen and then blanket stitched with coloured wool. Patchwork cushions, of velvets and silks joined by featherstitch, lay on the sofa and embroidered ‘spiders web’ mats were dotted round on the piano and other surfaces. Crochet mats were on the wash stands and dressing tables. All the girls had brush and comb bags of Holland cloth embroidered with their name, which they kept in their bedrooms.”

The history of the docks is very much focused on maritime life, industry and a working environment. However for the children of Albert Parade it was also a place to play, as the oral history transcript reveals:

"The docks were Mrs Parry’s playground she and another girl used to slide down the heaps of sand that Ables kept on the south quay of Canning Half Tide dock and also used to slide down on door mats down the slides in the graving docks."

Creating new memories

Along with revealing the archaeology, community excavation allows us to create new memories on the waterfront. Our volunteers can gain new skills in archaeology but also a sense of community and place. Linked to the excavation uncovering more of the Royal Albert Dock’s past, we held a variety of outreach events to enable visitors to discover more about what we find. You can find out more on our Piermaster’s Green community excavation page.