Meticulous observations by women at the Walker

It was a real privilege to work on Lubaina Himid’s exhibition Meticulous Observations and Naming the Money at the Walker Art Gallery in 2017/2018. Lubaina, pictured here at the Walker, is a truly inspirational figure and her display presented the work of a number of other groundbreaking women artists.

The theme of International Women’s Day 2018 was #PressforProgress, a call for gender parity. The representation of women artists compared to male artists in the Western art world, including at institutions like the Walker, has been infamously unequal. This is, unfortunately, especially true for women artists of colour.

Hosting Lubaina Himid’s striking display Meticulous Observations and Naming the Money at the Walker Art Gallery was a reminder that fighting institutional sexism isn’t enough; we must fight institutional racism, too. Lubaina, pictured above, has long championed the creativity of Black women artists, and her display at the Walker exemplified this.

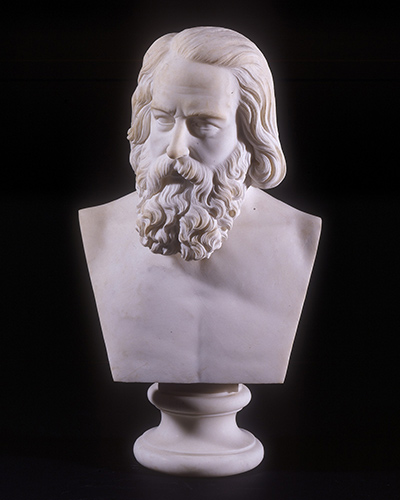

For Meticulous Observations Lubaina presented a selection of artworks by women artists, mostly from the Arts Council Collection. The starting point for this project was the Walker’s 1872 marble sculpture of Henry Longfellow by Edmonia Lewis. This sculpture is very important to Lubaina. Longfellow was a well-known American cultural figure, whose poetry influenced popular European and American views of Native American culture. His description of Native American people’s lives inspired artist Edmonia Lewis. She was the daughter of a Native American (Chippewa) mother and an African American father. This portrait reflects her admiration for Longfellow.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow by Edmonia Lewis, 1872. Walker Art Gallery.

Accepted by H M Government in lieu of Inheritance Tax and allocated to National Museums Liverpool in 2003

For the display Lubaina positioned Lewis’s sculpture so that Longfellow seemed to be looking directly at a ‘Ship’ bowl, from National Museums Liverpool’s Decorative Arts collection. A group of enslaved people are depicted on the side of the bowl. This intervention introduces themes running through Lubaina’s exhibition, including the ways in which the transatlantic slave trade has been disguised and glamourised and its legacy of institutional racism.

It also demonstrates Lubaina’s dedication to the promotion of women artists of colour. The show includes a work by Lubaina called 'Scenes from the Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture' (1987). This group of 15 watercolours depicts moments from the life of Toussaint Breda (1746-1803), an enslaved man who led the Haitian slave revolt of 1791. He was instrumental in saving Haiti from Napoleon, and is a very important figure in Black history. His actions led to Haiti becoming the first free colonial society to reject race as the basis for social status.

Lubaina’s paintings are accompanied by handwritten captions, which ask questions like ‘who cooked the / mid-day meal?’ and ‘who will do / the laundry?’. In this way Lubaina draws attention to the historically un-celebrated acts of everyday care and support that make heroic deeds possible. Since care work has historically been carried out by women, this artwork asks us to revise our views of a world history traditionally written from a white, Western, male perspective.

Scenes from the Life of Toussaint L'Ouverture: 5 (installation shot), 1987, Lubaina Himid. © the artist

This exhibition promoted the importance of close relationships, and not just between women. There was work about family and friends by women artists of colour, whom Lubaina has long championed, including Claudette Johnson and Veronica Ryan. There was also work by Prunella Clough, who used to visit industrial sites to draw with writer John Berger. Friendships with men and women were incredibly important to artist Frances Hodgkins, who struggled to gain recognition as a serious artist because she was a woman.

Trilogy (Part Two) Woman in Black, 1982-1986, Claudette Johnson. © the artist

Lubaina’s exhibition created opportunities for us, too, to have intimate encounters with the artists and their work. All of the artworks give a sense of you being in the room with the artist. Paintings by Bridget Riley and Lisa Milroy are charged with the artists’ presence; we know they have been there. This sense of presence is an important aspect of Lubaina’s own work.

Naming the Money (2004), a series of 100 unique cut out figures, gives faces and voices to people who were enslaved as a result of the transatlantic slave trade. For this display Lubaina placed 20 of these life-size painted cut-out figures throughout the permanent collection displays at the Walker, where we could get close enough to read poems fixed to their backs that tell us who they were.

Alile / POLLY shown alongside Frederick Sandy’s ‘Helen of Troy '

While some of the artists represented in the exhibition are united by friendship, all of the artworks in this show could be said to share a concern with how women think, feel, remember and make meticulous observations across generations and experiences. They all present images of fleeting beauty, the kind of thing we might blink and miss. An amber wasp surrounded by glistening rain drops is captured in a photograph by Tacita Dean. A still life of cutlery and napkins by Lisa Milroy quietly draws our attention to the people who might use them. Lubaina set up the image of an imaginary bird flitting from Avis Newman’s 'Bird Box 'La Scatola dell’Uccello' to Alison Wilding’s 'Green Beak'.

This display was about seeing value in our everyday domestic lives and relationships. It suggested that to make such meticulous observations is uniquely tied to the experience of being a woman. Lubaina Himid gently challenged the dominance of the still all-too pervasive idea of the artist as a white male genius, working in isolation. Making art, this display suggested, is a feminist issue.