Spotlight on: Roman sculpture

Statue of Athena (the 'Ince Athena')

Ancient marble sculpture is irresistibly attractive: there are strong, ideal and sensual bodies, elaborate folds and drapery, complex hairstyles and realist or ideal faces to admire. For centuries Ancient Classical sculpture came to epitomise beauty, to connect physical beauty with spiritual one and often to promote virtue and good citizenship. But is there more than meets the eye?

Let us try and imagine the general context of Roman sculpture. For example, where were statues displayed, what was their purpose and who made them? We may often know very little about their original archaeological context (Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli being the most common information that Henry Blundell was given by antique dealers) but their size, type and comparisons with similar examples in museums and collections all over the world, together with recent research in the general context of Roman sculpture, can give us some indication of what they may have been intended for.

One first thing we need to remember is that many statues and busts in museum collections were part of a particular Roman architecture, whether public or private. Specific features of busts and statues held specific meaning for their ancient viewers: for example the hairstyles, expressions and postures of an Emperor’s portrait represented his particular choice and communicated the ideas the Emperor wished to express.

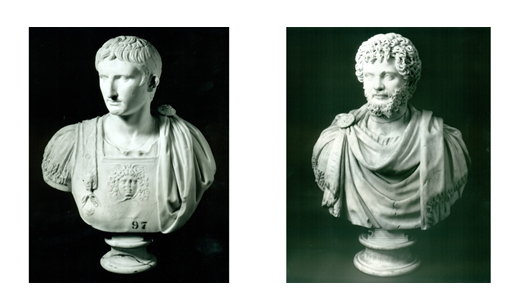

Bust of the Emperor August (left). Portrait of Septimus Severus (right)

The Emperor’s portrait had to be easily identified and recognised. In remote parts of the Empire such a portrait was a reminder of his presence. The style he chose to be represented had also to be different to previous styles by other Emperors. Certain types became extremely popular: for example the Prima Porta portrait of the Emperor August or the Serapis type of portrait of Septimus Severus, characteristic for the distinct four corkscrew locks. The latter is often assumed to have been inspired by Septimus’ travels in Egypt (199/200 AD) but as Jane Fejfer discussed, it may have been down to the influence of portraits of private individuals which expressed luxury and cult. It is often difficult to precisely date Imperial portraits, especially if they were used posthumously.

Statue of Togate Man (59.148.48)

Many Roman statues had inscriptions which gave important information about the person honoured and even the reason for receiving such honour. However many such inscriptions are often lost. Statues represented members of important aristocratic families but there are also many statues of important local individuals such as magistrates, priests, and benefactors, or even actors and athletes. To be honoured with a statue you would have to make a significant financial contribution towards your city. Competition among private individuals was fierce: some had to wait years before they were awarded a statue. The toga was not simply the costume but the symbol of Roman citizenship: our full togate man clearly expresses that honour. But statues and particularly busts were not just in public spaces; Roman villas and tombs also had them: to honour the dead, to remember the ancestors or to refer to significant relatives and to make meaningful associations. Portraits of important Emperors, philosophers and men of learning in private villas often aimed to emphasise the status, intellect and political significance of the owners.

Statuette of Epicurus (59.148.44)

Finally it is also easy to forget the people who made the statues and busts: testimonies about specific Roman sculptors are rare but we know that there were many different workshops. The style of the workshops in the East part of the Roman Empire was very different to the West. There was a preference for partial nudity and the himation and it was much more common to have portraits of athletes.

The Imperial court controlled prototypes made in wax and clay for Imperial portraits but different workshops had the responsibility of producing copies of the prototype. Even within the same workshop there was great variation to suit different contexts. Although we know a lot about the 16th and 18th century restorers and artists and the practices of assembling sculptures and portraits from different pieces, the Romans also re-used and recut parts of sculpture. Especially during the Early Empire in the 1st AD sculptors had to economise on good quality marble and often constructed a sculpture from different pieces.

You can explore ideas about production, context and meaning in Roman and 18th century in our Ince Blundell Roman sculpture collection online and also in Elizabeth Bartman’s catalogue of the ideal statues and busts.